The Korean Wave, or Hallyu, has been spreading across Asia for more than a decade, often referred to as the “Asian Wave” (S. Lee, 2019). As Hallyu has emerged as a key factor in South Korea’s economic competitiveness, extensive research has been conducted on the Korean Wave in Malaysia as a “reception phenomenon” (Hong, 2021). Scholars have noted the impact of the Korean Wave on the Malaysian media industry (H. Park & Har, 2019; J. Yoo, 2020), entertainment industry (Y. L. Lee et al., 2020), tourism (Zaini et al., 2020), and fashion industry (Jalaluddin & Ahmad, 2011). Following the surge of interest in Korean content available on global over-the-top (OTT) platforms like Netflix, studies have focused on key factors contributing to the popularity of Korean dramas in the Malaysian market (Ariffin, 2016; Ariffin et al., 2018a).

However, alongside the immense popularity of Korean content, anti-Korean Wave sentiments have emerged, largely attributed to cultural conflicts with Islamic religious norms and values (Ahmad & Beng, 2016). Simultaneously, discussions on the need for government-level support for the cultural industry have expanded, recognizing the economic effects of drama content on related industries such as tourism and fashion. The Korean government’s support policy has been credited for the success of the Korean Wave, prompting calls for comprehensive policy support for Malaysian popular culture (Ariffin et al., 2018b) while maintaining the identity of an Islamic nation (Mansor et al., 2019). As part of Vision 2020 (or Wawasan 2020 in Malaysian), a long-term government objective for Malaysia to become a fully developed nation by the year 2020, the Malaysian government announced plans to foster the cultural industry as a major contributor to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and introduced a strategic framework for the development of Malaysia’s creative industries sector, like DIKN (Dasar Industri Kreatif Negara or in English, the Malaysian National Creative Industry Policies (Barker & Beng, 2017).

This study aims to examine changes in media discussions related to Korean dramas in Malaysia, a core region of the Korean Wave, to understand the significance of the shifts in the reception and expansion of Hallyu as a “model.” The study focuses on the impact of global OTT services like Netflix and the role of Malaysia as a key hub for the Asian-Korean Wave. The discourse analysis approach is a suitable methodology to interpret phenomena of popular culture, such as the Korean Wave, to uncover public perceptions (Baek, 2015).

Literature Review

The OTT Effects on the Korean Wave

Research on the Korean Wave has expanded across various academic fields since the phenomenon was first observed overseas in the late 1990s. Studies have sought to identify the main factors contributing to the Korean Wave in Asia, such as cultural proximity (E. Yang, 2006; S. Yoo & Lee, 2001; Yoon, 2009), while communication studies have examined the phenomenon as a sign of a global tectonic shift dismantling the universal and hierarchical flow order seen from the perspective of cultural imperialism (H. H. J. Cho, 2003). The Korean Wave discourse (S. Yang & Lee, 2022) is expanding with the evolution and expansion of global OTT platforms. However, as many OTT studies have focused on industrial and regulatory policy-oriented approaches, research considering the “Netflix effect”[1] at a larger level, encompassing the policies of host countries and the global value chain, remains limited.

Discourse analysis is crucial in examining the change in discourse, as it allows for the confirmation of shifts in social consensus and logic constituting the rationality of major texts. Discourse in a specific country is formed and developed through the participation of multiple subjects and is captured, collided, and spread through news (D. Park & Lee, 2022). Therefore, analyzing media texts from key periods can help identify the core claims and arguments of major actors in the region and how consistent and conflicting claims coexist, clash, and expand.

The growth of global OTT platforms has been an important factor in the transformation of discussions surrounding media and content, unlike broadcast media, which can be subject to the influence of existing national policies and regulations. Global platforms that can distribute content directly through online communication networks have caused anxiety about the intrusion of heterogeneous cultural elements and the inability to control them, prompting negative responses from many countries. This was also the case in Korea, but interestingly, as opportunities for the expansion of the global Korean Wave through Netflix also increased, there was a delicate balance in the discussion about perceiving Netflix as a partner rather than a simple invader. Media discussions related to this utilize strategies to secure their own legitimacy regarding the duality of invaders and companions, mobilizing logic such as social protection and economic growth.

The Korean Wave in Malaysia

Research on the Korean Wave in Malaysia is still in its early stages, with limited attention compared to studies focused on Northeast Asia (Lim & Chae, 2014; H. Park & Har, 2019; Shim, 2013). Studies on the Korean Wave in Malaysia have primarily focused on intensified cooperation and flourishing cultural exchanges with Korean content (C. Cho, 2007; K. Choi, 2019) and the economic effects of the Korean Wave (H. Bae & Lee, 2020; E. Cho et al., 2017; K. Choi, 2019; S. Yoo & Lee, 2021). However, there has been a lack of extensive research from a cultural perspective that takes the historical and social context into account (Kwon, 2013). While some studies have explored the Hallyu consciousness among Malaysian people (K. Cho & Jang, 2013) or changes in the reception of Korean dramas in Malaysia (K. Kim, 2016; Kwak, 2017), they have mainly focused on strategies to enhance the impact of the Korean Wave, limiting the comprehensive understanding of discourse on the Korean Wave in the Malaysian context.

Research Methodology

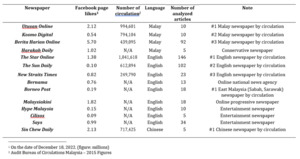

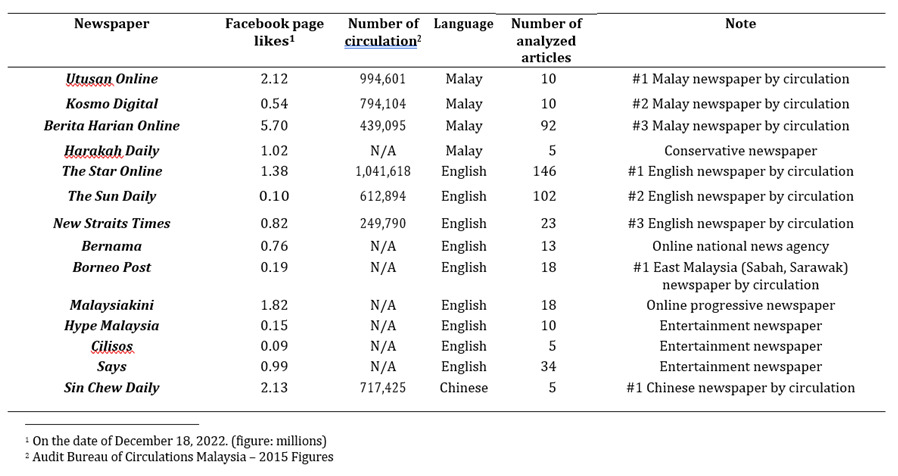

This study seeks to understand changes in local Korean Wave discourse by analyzing major media discussions about Korean Wave content in Malaysia before and after the introduction of the OTT platform. For this purpose, 14 Malaysian daily newspapers available online were selected as the target of analysis. The selection criteria largely considered three factors. First, in order to ensure the representativeness of the analysis subject, the newspapers with the highest circulations, with a minimum daily circulation of 240,000 were included as the analysis subject. Second, to reflect Malaysia’s diversity, Malay, English, and Chinese newspapers were included in the analysis. According to existing research in Malaysia, the difference between newspapers published in various languages, such as Chinese, English, and Malay was clearly revealed (Wui & Wei, 2020) Therefore, Malay, Chinese, and English newspapers were selected as the analysis target for this study. For Malay and English newspapers, the three newspapers with the highest circulation based on the Malaysia Publishing Booth Corporation in 2015 were selected as the target of analysis, and for the Chinese language newspaper, the one newspaper with the highest circulation, Sin Chew Daily, was selected as the subject of analysis. This is because the proportion of the Chinese-speaking population is lower than that of Malay speakers. As of the third quarter of 2022, the Malaysian population consists of Malays (70.0%), Chinese (22.7%), Indians (6.6%), and others (0.7%) (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2022). Additionally, we wanted to reflect the geographical characteristics of Malaysia, which consists of two regions, East Malaysia and West Malaysia; since the first seven newspapers selected were published in West Malaysia, a newspaper published in East Malaysia, the Borneo Post, was also included in the analysis. The Borneo Post is the daily newspaper with the highest circulation in East Malaysia (Chua et al., 2017). Third, in order to increase the representativeness of online news whose circulation cannot be counted, newspaper sites with a high number of Facebook usage behaviors (likes) were targeted for analysis. Facebook accounts for the largest share of Malaysian social media market is important in forming public opinion. This is a selection method that has been proven valid in previous studies that analyzed the dissemination of online news portals about the Malaysian general election with a high social media presence (Kasim & Sani, 2016). Fourth, newspaper sites representing conservative and progressive ideologies were selected. There are differences in the way newspapers report the same event depending on ideological tendencies (Sualman et al., 2017). The conservative newspaper Harakah Daily, owned by the Islamic political party (PAS), and Malaysiakini, a progressive newspaper, were included in the analysis. Fifth, Internet newspapers specializing in entertainment were included as subjects of analysis. Existing research proposed a research method that included major newspapers with high sales volume and small and medium-sized newspapers in the subject of analysis (J. Bae, 2012). Although professional Internet newspapers are non-mainstream newspapers, they can identify trends in the Korean Wave as they are related to the Korean Wave, which is the research topic of this study. Considering representativeness, the analysis target was selected mainly from Internet newspaper companies with a high number of Facebook likes to reflect general public views. The media companies selected for analysis based on the above criteria can be summarized as shown in Table 1.

The analysis targets were selected based on the relevant articles reported over six years from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2022. The reasons for selecting the period after 2016 as the analysis period are as follows: First of all, Netflix, notably the most representative global OTT platform, launched its service in Malaysia in 2016. Second, in 2016, Netflix contributed to the spread of Korean Wave content by bringing about new changes in the areas of content production, distribution, and consumption (J. Lee & Jeong, 2020). According to previous research, unlike existing broadcasters, Netflix provides users with temporal and spatial freedom, which has a positive impact on the growth of the Korean Wave market (S. Kim, 2021). Third, as the OTT market grows, domestic and foreign OTT operators beg to bring Korean Wave content as a way to increase competitiveness. According to previous research, Malaysian users appear to use OTT platforms that have a large amount of Korean content represented by Korean dramas (Isa et al., 2019). Therefore, we can say that the Korean Wave phenomenon spread rapidly after Netflix entered the Malaysian market in 2016.

The search keyword for article sampling was set to “Korea(n) drama,” and 491 relevant articles were reviewed for analysis, as shown in Table 1. The sampled articles are largely divided into the three domains of culture, economy, and policy which are commonly employed in discourse analysis uncovering the complexities of cultural reception such as the Korean Wave (J. Choi & Ryoo, 2012). The culture area is divided into general, gossip, criticism of Korean culture, critical of Malaysian culture, such as Malaysia dramas and actors, and society, such as articles analyzing Malaysian social phenomena through the lens of Korean dramas. In the economic field, articles were divided into those that dealt with the connection with Korean dramas, such as articles examining the impact of Korean dramas on various industries including intellectual property, tourism, and those that had simple advertising purposes. Policy discussions were conducted on policy articles from the home country and neighboring countries related to Korean dramas at the sampling stage and were not classified separately. As a result of this classification, 261 brief news without in-depth coverage or detailed discussion, gossip articles, and advertising articles, and unclassified articles were excluded from the text analysis, and 230 articles were reviewed. Among 230 articles, 70 were positive, 12 were negative, and 148 were neutral. In Figure 1, the trends regarding the number of articles related to Korean culture (criticism of Korean culture), Malaysian culture (critical of Malaysian culture or society), economy (Korean dramas), and policy (Policy) were illustrated.

Based on the data collected above, the article texts were largely divided into cultural discourse, policy discourse, and economic discourse. Figure 1 shows the quantitative trend of articles by field during the analysis period.

In the figure above, the number of related articles has increased significantly starting in 2020, when the global performance of Korean dramas through Netflix expanded significantly amid the spread of COVID-19. For specific analysis, the authors reviewed the original text of the articles and attempted to understand the flow of discussion by period and area based on key claims and arguments. At this time, the authors especially paid attention to changes in major discussions that occurred in the years 2019–2020. The results of the analysis were presented by summarizing and quoting the main discussions. However, quotations from the main text of the article were translated from the original text in consideration of the length.

Results

The results can be broadly divided into two periods: 2016-2019 and 2020-2022. From 2016 to 2019, the discourse on the Korean Wave was primarily focused on “culture,” with a prevailing “national culture protection theory” supporting a defensive perspective. However, starting in 2020, the discourse has continually evolved, emphasizing the economic and policy implications of the Korean Wave. Appendix A shows a summary of the articles mentioned below.

2016-2019: Cracking of Cultural Protection Theory

During this period, the Malaysian media often portrayed Korean dramas negatively, comparing them to instant ramen, which is convenient but has negative health effects(Berita Harian, November 3, 2017). The popularity of K-pop was associated with “celebrity worship syndrome,” raising concerns about the impact on Malaysian teenagers (Berita Harian, October 2, 2016). The Korean Wave was perceived as spreading a culture that goes against Islamic values and beliefs, which is referred to as yellow culture (or budaya kuning). Fandom culture was criticized as a type of mental illness that sexually seduces Muslim women, particularly married women, which was seen as problematic in the conservative cultural norms of Malaysian society.

The shameful image of praising that celebrity for being handsome or this celebrity for being good-looking should disappear. As if she were her husband. She is overly preoccupied with Korean male celebrities. People are obsessed with the idea that Korean celebrities are more romantic. (Says, February 2, 2017)

Alongside the discourse on protecting domestic culture, concerns emerged about the potential negative impact of the Korean Wave on the Malaysian cultural industry. The influx of Korean Wave content was seen as a threat to the development of the country’s relatively weak cultural industry (Berita Harian, November 26, 2017). The increasing programming ratio of foreign dramas was believed to decrease the programming ratio allocated to domestic dramas, resulting in reduced work for Malaysian producers, directors, and actors, and causing many industry workers to lose their jobs.

However, concurrent with these discussions, there were also acknowledgments of the achievements of the Korean Wave. The iconic Korean drama Winter Sonata was recognized for introducing the world, including Malaysia, to Korean dramas and contributing to the improvement of Korea’s national image and status (Borneo Post, May 14, 2017). The series was credited with exposing Malaysians to various aspects of Korean culture, including food, fashion, beauty, drama, and music, which remain a passion to this day.

Thanks to a concerted effort over several decades, K-pop and Korean sophistication began to capture the world’s attention. Young people are fascinated by Korean culture, and young white women are learning Korean to properly enjoy Korean cuisine. (Malaysiakini, June 8, 2018)

The results from this period can be summarized as follows: The theory of protecting national culture from a defensive perspective was mainstream, with many discussions focused on the culture area. However, as Netflix’s influence grew and awareness of Korean dramas in the global market increased, voices calling for this to be used as a new economic opportunity also emerged. This shows that cracks were appearing in the existing landscape centered on defensive discourse. Cultural conservatism consistently maintained a defensive attitude, while opposing discussions from cultural and economic perspectives coexisted, suggesting the possibility of change.

2020-2022: Attention to the Positive Value of the Korean Wave and Growth of Domestic Industry Development Theory

Starting in 2020, a significant shift in media discourse occurred, with a greater emphasis on the achievements of Korea’s cultural industry and the competitiveness of the country’s cultural industry, rather than focusing on “protecting national culture.” The majority of culture-related articles discussed the need for cultural policies and strategies, highlighting the economic effects and profits of the Korean Wave.

K-pop such as BTS, popular series such as Squid Game, and the movie Parasite have conquered the world. We do not lack talent and creativity, so all we need is help from all government departments. (Utusan Online, December 25, 2022)

Many articles argued that the Korean Wave’s development was facilitated by government support and a better creative industry environment, comparing the culture-related policies of Korea and Malaysia. The local media emphasized the competitiveness of the Korean Wave, which has spread globally through OTT platforms, and called for policy support measures based on Korea’s best practices. The global craze for Korean music, dramas, and movies was seen as proof that the entertainment industry has become an important industry for economic growth.

Furthermore, the Korean Wave was recognized for its potential to contribute to social and cultural benefits, as well as economic development. Importantly, the conservative newspaper Harakah Daily suggested that Korean Wave content negatively impact the establishment of Muslim identity in 2010s, but in the 2020s, Korean Wave was suggested as a means to spread Islamic values to a wider region with its own cultural identity.

Korean dramas, once famous for their love stories and romantic genres, are expanding their influence by covering psychology, philosophy, and historical stories. Additionally, the fields of art and entertainment can be used as a medium to spread Islamic teachings. (Harakah Daily, September 7, 2020)

Korean dramas were even suggested as a means of addressing social problems in Malaysia, such as suicide and mental illness, highlighting the positive effects of the genre (Utusan Online, October 21, 2021). It was argued that many people watch Korean dramas to fill a void for family or personal reasons, using them as an escape while remaining well aware of reality.

The discourse in the 2020s has largely focused on the economic effects and positive aspects of the Korean Wave from the perspective of a domestic cultural industry promotion strategy. The Malaysian Ministry of Communications and Multimedia (KKMM) announced a project to be a strong candidate for the Oscars through the National Film Development Corporation (FINAS), emphasizing the need for budget allocation and strategy establishment based on the Korean case (Malaysiakini, June 16, 2020). Korea’s success in producing K-content was cited as an example for Malaysia to follow in fostering its own “creative industry” (Berita Harian, September 28, 2021).

It took 30 years for Korea to win an Oscar, so let’s create a budget and establish a strategy. (Malaysiakini, June 16, 2020)

By 2022, the discussion expanded to the need to learn from Korea about the entertainment cultural industry, including not only movies, dramas, and K-pop but also food and tourism, which are derivatives of the Korean Wave, to foster Malaysia’s industries (Malaysiakini, September 29, 2022; Utusan Online, December 11, 2022). The discourse emphasized the ripple effect of the Korean Wave by mentioning Korea’s tourism industry, and many media outlets claimed the need for such a “benchmark.”

We should follow Korea’s example of being proactive and progressive in expanding the influence of film and music around the world. (Utusan Online, December 11, 2022)

The above discussion can be summarized as follows: Starting with Japan in 2015, Netflix entered the Asian market, including Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia, in 2016 and began paying attention to and strategically investing in Korean dramas with high appeal in the region. The non-face-to-face situation caused by COVID-19 encouraged content consumption through global OTT platforms, providing an opportunity for Korean dramas to be recognized globally. Squid Game which was released on Netflix in 2021, became the world’s most watched program as one of the most successful works in Netflix’s history. As Korean dramas became huge hits on Netflix, there was a big change in the way Malaysian media perceived and reported on Korean culture. Korean media, such as K-pop and K-drama, were often seen as a form of national culture protection theory, with concerns expressed about the impact of Korean media on local culture and values. However, as the influence of Netflix as a global OTT platform grew and the popularity of Korean dramas on the platform increased, the discourse surrounding Korean Wave content in Malaysia, which had previously been focused on protecting local culture, shifted to an economic value-oriented perspective. The Malaysian media’s discourse on Korean Wave has begun to shift to a more favorable perspective, reflecting an increased recognition and understanding the economic value of Korean content, and how Malaysia could do something similar in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results affirmed that there was a shift in attention to the Korean Wave as Figure 2 shows: First, since 2016, when Netflix expanded its influence into the global market, the mainstream focus was on yellow culture, with supporting national cultural protection theory but there was a shift in paying attention to the economic value of Korean Wave as a benchmark and a model. Secondly, there is a change from negative cultural discourse that supports the national culture protection theory to positive economic discourse. The positive cultural effects of the Korean Wave began to emerge as a counterargument to the existing logic of protecting national culture. Third, cultural protection discourse changes into industrial development discourse when Korean dramas were successful in global OTT platform. There have been changes in discussion that seeks to see the expansion of global OTT platforms and local content as an opportunity rather than a crisis in the regional context of Malaysia paying attention to the economic value of culture. The window of opportunity opened by the encounter between Korean dramas and Netflix was a shift in the frame of interpretation from culture-identity to culture-economy in Malaysian Korean Wave discourse.

This study contributes to a more holistic understanding of the Korean Wave phenomenon in major Asian countries, particularly Malaysia, rather than viewing it as a special event limited to Korea. The multi-layered nature of the Korean Wave is highlighted through the examination of the changing landscape of discourse in the Malaysian media.

_drama(s)__in_malaysian_media.png)

_drama(s)__in_malaysian_media.png)

_drama(s)__in_malaysian_media.png)

_drama(s)__in_malaysian_media.png)