With the development of information and communication technology and the media environment, people can access content more freely than ever before. Over-the-top (OTT) services have made this possible (Chakraborty et al., 2023). OTT companies focus on securing users using subject-specific content, recommendation algorithms, and original content. Unlike traditional media, which simply supplies content, OTT services provide customized services to users, who can also select content based on their personal preferences (Menon, 2022). Companies related to OTT services are growing rapidly. Netflix, which has grown into a global OTT company, had 22,309 subscribers as of 2022. It supplies content to more than 190 countries in North America, Asia, and Europe (Statista, 2022). It is expected to attract more users through innovative services and interesting content (Shin & Park, 2021).

However, as users’ range of choices has diversified and become overloaded, the time spent thinking about what content to watch rather than watching content is increasing. These actions are similar to delaying purchases due to risk perception and searching for alternatives when consumers purchase specific products (Greenleaf & Lehmann, 1995). In other words, the user can watch content on TV as soon as they turn it on, but in the case of OTT services, they must find it on their own (Chen, 2019); thus, a “choice deferral” is necessary to watch content. Some people refer to this as the “Netflix syndrome”—the act of spending more time choosing than actually watching content (H. Kim & Choi, 2024). If Netflix syndrome persists, users are more likely to experience stress, irritation, and suspension of viewing rather than having fun and feeling interested in the content.

To understand this phenomenon, this study applies psychological theories that explain the effects of excessive choice on decision-making and user experience. The “paradox of choice” theory (Schwartz, 2004) posits that an abundance of options can lead to decision fatigue and increased psychological distress. Additionally, the concept of affective ambivalence (Larsen et al., 2001) explains how conflicting emotions can make decision-making more difficult, further exacerbating the deferral of choices. By integrating these psychological perspectives, the present study provides a theoretical foundation for analyzing OTT users’ decision-making behaviors and their psychological consequences.

In other words, when many options to purchase a specific product are available, people develop negative feelings (Schwartz & Ward, 2004). Schwartz saw that if people had too many options to choose from, they would waste time trying to determine the optimal conditions and eventually increase stress (2004). To address the problem of choice fatigue, where users spend more time on selection than on actual viewing, OTT platforms such as Netflix have launched the “Play Something” feature, which can play content immediately according to the user’s tastes. However, very little research has explored OTT choice deferral and its psychological consequences for users.

OTT use-related theories provide meaningful analyses. Generally, people are interested in things that they choose for themselves. However, in environments where it is difficult to choose, they experience negative emotions (Bjørlo, 2021). Negative psychological phenomena may occur depending on OTT viewing choice deferral. Users are likely to explore more strategically and carefully choose, recalling past experiences to reduce the “failure experience” of products and services. In particular, users who experience negative psychological phenomena due to deferring choices may be more interested in solving these problems (Rogers, 1992). With the popularity of streaming platforms such as Netflix and Disney+, viewers have a more diverse range of platforms and content to choose from, but this vast amount of content also creates some choice difficulties for users. Surveys show that 46% of streaming consumers are overwhelmed by the ever-increasing number of platforms and programs, making it more difficult to find specific programs in specific locations (Nielsen, 2022). In the realm of consumption, increased choice intensifies consumer stress. It can be inferred that streaming media users are likely to face increased stress and other psychological issues when faced with more choices, highlighting a gap in the research in this area. Research on TV viewing and mental health suggests that people who watch TV for extended periods report lower levels of life satisfaction, and that prolonged TV viewing is associated with higher levels of material pursuits and anxiety (Frey et al., 2007). In the streaming era, binge-watching has emerged as a significant topic. A meta-analysis by Alimoradi et al. (2022) links binge-watching to various mental health issues, including stress, anxiety, and sleep problems. However, few studies have explored whether choice deferral associated with the diversity of choices on OTT platforms affects users’ psychological well-being, and the understanding of how choice overload affects viewers’ psychological well-being in streaming environments remains insufficient. Considering the above, the goal of this study is to explore the issue of choice deferral, which may arise from an overwhelming number of content choices, and its potential psychological impacts in the context of OTT platforms. Specifically, we will focus on analyzing how too much content choice affects users’ information processing, decision deferral, and the psychological responses associated with it. By delving into this area, we aim to fill the research gap in the OTT field regarding choice deferral and its psychological consequences caused by too many choices, providing new insights into digital media consumption behavior.

In addition, people are more likely to share their preferred content with others. They provide knowledge through active social interactions and may change incorrect decisions. Therefore, it is possible to analyze whether the social capital explained by human networks can reduce users’ OTT viewing choice deferral. This study posits that affective ambivalence, known as product purchase avoidance sentiment, along with social capital, could affect OTT viewing choice deferral. This is because it was believed that risk-averse thoughts and attitudes could have a negative effect on the choice deferral variable in situations where various options are available. Considering that an online environment where product purchases are active (Liao & Keng, 2014), involves many thoughts of failure, affective ambivalence can be seen as an important variable in explaining choice deferral.

South Koreans were selected as the subjects of our study for several reasons. First, South Korea has excellent Internet access. According to the National Informational Society Agency, the Internet utilization rate of the general public in South Korea is 99.5%, which is the highest in the world (National Informational Society Agency, 2022). The fact that users can access OTT services anytime and anywhere is a significant advantage in South Korea. Second, in South Korea, there is fierce competition among global OTT companies, which means that a significant amount of content is available for users to select. In fact, as revealed by the status of “K-content,” not only overseas platforms such as Netflix and Disney+ but also Tving, Watcha, and Coupang Play are introducing various services and content to secure subscribers in South Korea. Additionally, these companies are expanding their investments in South Korea and engaging in strategic alliances with producers (Nam et al., 2023). Third, the number of OTT users in South Korea exceeded 20 million as of February 2024. Netflix was the most popular OTT service with 12.37 million users (39%). This is followed by TVing with 5.51 million (17.4%) and Disney+ with 2.77 million (8.7%) (Jeong, 2024). OTT services are combining with digital technologies to further expand their audience. As the market becomes more competitive, it is important to understand the characteristics of OTT users in Korea.

Research on TV viewing and mental health indicates that heavy TV viewing (Frey et al., 2007), binge-watching (Alimoradi et al., 2022), and certain types of content (Carmichael & Whitley, 2018; Evans et al., 2021) can negatively impact social well-being, typically manifesting post-viewing. Contrasting with traditional TV, which provides immediate gratification via a remote control at a negligible marginal cost, OTT platform users must actively select their content before engaging in viewing behavior. This selection process prior to viewing may have a detrimental impact on the user’s psychological well-being. Much like consumers in retail who delay decisions when faced with abundant choices (Bjørlo et al., 2021), OTT platform users might also experience decision delay and negative emotions due to choice overload. However, research on the psychology of OTT platform users during the pre-viewing selection stage remains limited. This study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How does choice deferral during the pre-watching stage on OTT platforms contribute to users’ psychological stress?

RQ2: What are the key factors that influence users’ choice deferral during this selection process?

To answer these questions, this study examined OTT content selection and users’ psychological responses through the variables discussed in consumer psychology, management, and journalism. Specifically, the abundance of content on OTT services is recognized as a problem, and variables such as social capital and affective ambivalence are introduced to reflect users’ social and psychological characteristics. In addition, a model is presented in which OTT viewing choice deferral can be increased and ultimately lead to OTT stress. This study provides academic implications in that it empirically reviews how user behavior regarding OTT services affects stress. In particular, it shows that users have negative perceptions of OTT services in environments with excessive content. As technological changes ultimately have a significant impact on the entire content market (Smith & Telang, 2016), identifying user perceptions of OTT services is also considered significant at a practical level.

Previous studies have extensively examined the effects of choice overload in e-commerce and traditional media contexts, revealing its negative psychological impacts, including decision fatigue and stress (Schwartz & Ward, 2004). Recent studies have examined the impact of OTT usage on the lives of Generation Z. Tayade et al. (2024) pointed out that OTT services provide an important means of relaxation for Generation Z in increasingly competitive and stressful environments. However, this study fails to address another form of stress that may arise during the content selection process. Given that selection stress in the initial stage of OTT service use can significantly affect user experience and psychological well-being, further research on this aspect is necessary.

Literature Review

The Relationship Between Content Excess and OTT Viewing Choice Deferral

OTT services have become a central medium for media consumption (Chakraborty et al., 2023), and the market is experiencing continuous growth. Despite this expansion, users often face difficulties in selecting content due to the overwhelming number of available options. Such decision-making processes are associated with time-consuming efforts and post-decision regret (Schwartz, 2004). We hypothesize that these behaviors may contribute to user stress. Choice deferral refers to the combined result of deciding which brand to choose and whether to choose, with its likelihood depending on the ease of making the selection (Dhar, 1996). Thai and Yuksel (2017) define choice deferral as “a phenomenon whereby making choices from extensive assortments leads to adverse outcomes and negative perceptions.” Choice overload may be a major cause of delayed selection. Iyengar and Lepper’s study (2000) were the first to find that offering more than a certain number of choices to the decision maker may have significant demotivating effects on the decision-making process (S. S. Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). In consumer research, choice overload refers to the point at which consumers have difficulty comparing or understanding products due to exposure to more information or alternatives than they can handle (Walsh, 2007). Indeed, after the emergence of an information society that suffers from over selection (Toffler, 1971), many have witnessed the negative phenomena caused by it in various areas. Particularly online, dealing with a large amount of fragmented information can be cumbersome (McCabe et al., 2015). Additionally, the online environment, without physical constraints on providing or collecting information, leads to consumers being more likely to be exposed to information online than offline.

Choice overload, often observed in online buying, and offline choice deferrals due to choice overload are of interest. In the offline domain, consumers evaluate alternatives by spending additional effort and time coping with choice overload situation (Payne et al., 1992). Similarly, previous studies have also suggested that deferral in selection is an outcome of choice overload (Greenwood & Ramjaun, 2020). A similar offline phenomenon was observed online. For example, online shopping consumers may delay purchasing decisions due to a large amount of information or alternatives (Cho et al., 2006), or use shopping carts to delay decisions (Kukar- Kinney & Close, 2010). An association between information overload and choice deferral has also been observed in the tourism domain (Greenwood & Ramjaun, 2020). Tourism studies have argued that online information or alternatives to tour products can cause users to experience choice overload and defer their purchase decisions.

Netflix had 956 titles available in Korea in the first half of 2023 (Lovely, 2023), while Netflix users only spent 9.48 hours per month viewing content in 2022 (S. Y. Kim, 2022), which means that consumers are exposed to an enormous number of content alternatives compared to the amount of content they actually use. Previous studies have also reported that information overload affects choice decisions (Greenwood & Ramjaun, 2020). Considering this, users are likely to experience choice overload due to the large amount of content available from OTT services, and as a result, they may be likely to defer choosing content when using these services. Thus, this study presents the following hypothesis:

H1: Content overload is positively associated with OTT viewing choice deferral.

The Relationship Between Social Capital and OTT Viewing Choice Deferral

The definitions of social capital are diverse and inconsistent. Putnam’s widely used definition of social capital includes social norms, networks, and trust (Putnam, 1993). The main characteristic of social capital is that it is formed through social relationships and individuals can participate in social relationships to secure information or social support (Rhee et al., 2005). Similarly, Bourdieu considers the individual material interests within a social network as social capital (1986). Studies have demonstrated that knowledge can be created by forming social relationships.

Network members are likely to be willing to share knowledge among themselves to keep the network stable (Yang & Farn, 2009). Additionally, they can access multiple types of information through their social networks (Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998). Trust, an element of social capital, binds social relations, providing members with the opportunity to obtain higher-quality information (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000). In the case of cohesive social capital, which is another social capital element, the higher the level, the stronger the ties are among members, reducing uncertainty and ultimately facilitating the spread of information (Granovetter, 1973). In addition, members easily sympathize with the information exchanged in a strong network and are more likely to cooperate with others in the network (Williams, 2006).

In addition, one study found that social pressure and perceived popularity are important factors in users’ decision to use OTT services (Lee et al., 2017). In other words, along with users’ interest in and enjoyment of certain content, word-of-mouth and ratings from others can have a meaningful impact on users’ content choices. Providing opportunities for positive social interaction and conversation with peers, family, and romantic partners constitutes a primary social consequence of content viewing (Palmgreen, 1988). This can be interpreted by applying the concept of social capital. Social capital encompasses the resources derived from social networks, including trust, shared norms, and information exchange (Bourdieu, 1986; Putnam, 1993). In the context of OTT services, these resources help users manage the abundance of content choices by facilitating decision-making through social interactions. For instance, trust among network members ensures that recommendations for specific shows or movies are perceived as reliable, while information sharing reduces the cognitive effort required to navigate content options.

This study synthesizes multiple definitions of social capital to highlight its relevance to OTT viewing choice deferral. While Bourdieu emphasizes the material benefits of social connections (Bourdieu, 1986), Putnam underscores the importance of trust and reciprocity (Putnam, 1993). In the context of OTT, these aspects translate to users’ ability to make quicker and more confident content decisions based on recommendations and discussions within their social networks. Conversely, insufficient social capital can hinder access to valuable content-related information, potentially leading to prolonged decision-making processes. According to Palmgreen (1988), sharing and discussing information about TV programs with others is a primary social outcome of content consumption. A lack of such interactions may result in limited access to relevant content information, increasing the cognitive burden on users and subsequently leading to choice deferral. In the context of OTT platforms, where users are often overwhelmed by the sheer volume of available content, social capital can serve as an essential resource for filtering and prioritizing content options.

Thus, the relationship between social capital and OTT viewing choice delay can be explained by the proposition that the higher the level of social capital, the greater the likelihood of information sharing or reception. The information benefits of social capital may help OTT users obtain more content-related cues from social relationships, helping them make faster decisions. In particular, if members who form strong ties recommend specific content, the user is likely to form a favorable attitude toward the content based on the trust relationship. Consequently, users can quickly select OTT content based on a high level of confidence. Therefore, this study assumes that an increase in social capital lowers the level of choice deferral and presents the following hypothesis:

H2: Social capital is negatively associated with OTT viewing choice deferral.

Relationship Between Affective Ambivalence and OTT Viewing Choice Deferral

Affective ambivalence is the simultaneous experience of oppositely valenced affect or emotions (Larsen et al., 2001). Previous studies have also seen the sequential experience of bipolar emotions as affective ambivalence (Ortony et al., 1988).

Consumer-related studies have defined affective ambivalence as a purchase avoidance emotion induced by cognition or emotions (Huang et al., 2018); thus, affective ambivalence is likely to be further facilitated in the context of product and service consumption with many alternatives. Previous studies of online shopping have consistently reviewed affective ambivalence. Many consumers use mobile devices to shop online, and they are more likely to experience affective ambivalence because they are exposed to a variety of product information using mobile devices (Ong et al., 2022). Some previous studies have proposed affective ambivalence as a major explanatory variable for OTT viewing choice deferral (Huang et al., 2018). Others have argued that ambiguous emotions, such as affective ambivalence, can increase aversion to the risk of choice, which may cause consumers not to want to complete the final selection process (Wang et al., 2022).

In the OTT content-viewing environment, users can experience affective ambivalence similar to online shopping. Users may have ambiguous feelings regarding what to choose in an OTT environment with many content alternatives. In this process, they perceive content benefits or losses and may experience aversion to risk. If this aversion grows, users may not be able to select the content to watch and may defer their decision. From another perspective, the OTT environment has characteristics that make it susceptible to affective ambivalence. Users can watch OTT content on mobile devices and smart TVs, and considering the claims of previous studies on online shopping (Huang et al., 2018), they are more likely to experience affective ambivalence in mobile OTT environments. Therefore, this study assumes that the higher the level of affective ambivalence experienced by users in the OTT selection situation, the more OTT viewing choice deferral is promoted, and it proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Affective ambivalence is positively associated with OTT viewing choice deferral.

The Relationship Between OTT Viewing Choice Deferral and the Stress of OTT Use

It is anticipated that as the delay in OTT viewing choices increases, the level of stress experienced during OTT usage will also be higher. Consumer-related studies have posited that as a result of choice deferral, purchases can either be postponed or conducted through alternative purchasing channels (Cho et al., 2006). Outside the purchasing environment, delayed behavior can reveal additional consequential variables. From a psychological point of view, delayed behavior can have negative consequences for individuals’ lives (Steel, 2007). Specifically, Ferrari’s research indicates that those who frequently delay behavior have high social anxiety and low self-esteem or self-control (Ferrari & Dovidio, 2001). Another study found that delayed behavior had a statistically significant effect on mental problems such as depression and anxiety (Harrington, 2005). Burka and Yuen argued that delayed behavior can cause internal states such as self-criticism, regret, and despair (1983). In summary, choice-deferral behavior can negatively affect an individual’s internal psychological state as well as external behaviors, such as consumer behavior.

Conversely, the relationship between choice-deferral behavior and negative psychological factors, initially a focus in psychology, has since expanded to other fields, including consumer behavior and pedagogy. However, few studies have been conducted on OTT viewing choice deferral or negative psychology. Therefore, based on choice deferral and discussions in several academic disciplines, this study suggests that OTT viewing choice can have a positive effect on user stress.

OTT services are leisure activities involving entertainment. Leisure activities help escape negative physical and psychological conditions. Nevertheless, users face choice deferral between OTT services, causing negative psychological states such as depression and anxiety (Harrington, 2005), or low levels of self-esteem or self-control. It is paradoxical that users experience negative psychological effects while watching OTT content, which they often do for relaxation or self-improvement. The current study assumes that users may face a negative psychological state if the level of OTT viewing choice for deferral content increases. Among psychological factors, stress was set as the dependent variable in the current research model. Stress is a negative emotion that humans experience when facing situations that are physically or psychologically difficult to handle (Lazarus, 1991). In particular, stress is directly or indirectly linked to disease (Cooper & Quick, 2017), which was also considered an important variable in this study.

Previous research in the field of TV viewing and mental health has highlighted that lower well-being is often reported by individuals who perceive their TV watching as uncontrollable and unpredictable, particularly when it involves a significant time investment by heavy users (Frey et al., 2007). This suggests that TV viewing is likely to contribute positively to well-being only when it is perceived by viewers as being within their control, predictable, and not excessively time-consuming. However, in the context of OTT services, the delayed decision-making process may lead to an uncontrollable and unpredictable investment of time, potentially causing stress among viewers. Therefore, we make the following hypothesis:

H4: OTT viewing choice deferral is positively associated with the stress of OTT use.

Methods

Research Model

Data Collection and Sample

Those who use a service without paying a direct subscription fee were generally less likely to be involved in the service (R. Iyengar et al., 2022). Therefore, this study targeted paid Netflix subscribers as its sample, as they are more actively engaged with OTT services. Their engagement allows for a clearer observation of choice deferral and related stress, aligning with the study’s objective to examine these phenomena in depth. We commissioned Macromill Embrain, a research company, to conduct an online survey between January 9 and 13, 2023. Macromill Embrain, which operates a panel of approximately 1.7 million members, hosted the survey on its proprietary platform. The survey was displayed to eligible panel members during the survey period, allowing those who wished to participate to access the survey link. Upon accessing the survey, respondents were presented with an initial screening question: “Which OTT services do you currently subscribe to with a paid subscription?” A list of ten OTT services that were available in South Korea as of January 2023 was provided as response options. Only respondents who selected Netflix as one of their paid subscriptions were eligible to participate in the final survey. This study adhered to ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection, and all responses were anonymized to ensure participants’ privacy. Data were stored securely and used exclusively for research purposes.

Participants were recruited through a quota-based sampling method that considered age and gender distribution based on the Korean Population Census data. In other words, after a quota was reached, panel members with those characteristics (e.g., female in her 20s) wouldn’t be able to answer even if they otherwise met the criteria. This approach ensured demographic diversity but does not represent a probabilistic sampling method. The sample of 443 paid Netflix subscribers provides insights into OTT user behavior, particularly in the South Korean market, which is characterized by intense competition and high levels of OTT penetration (see Table 1).

Measurement

Three independent variables were categorized as content characteristics, social factors, and independent factors. Additionally, this study includes parameters and dependent variables (see Appendix). Regarding the content characteristics factor, content overload was adapted from online shopping hesitation research (Demirgüneş, 2018). This scale for measuring online shopping hesitation was adapted from Sproles and Kendall’s (1986) consumer decision-making style scale (Sprotles & Kendall, 1986), which has been widely used in the research of online decision making (Ling et al., 2010). This study focused on the formation of social capital through social activities among social capital factors. For this, questions from a study examining the relationship between Internet use and interpersonal relationship formation were used (Nie et al., 2002). We adapted three items from this study. To maintain consistency with the measurement of other variables, we replaced “time spent” with “agreement” on the 5-point Likert scale. Next, affective ambivalence was measured using items adapted from consumer behavior studies (Chang, 2011; Huang et al., 2018) with a few modifications to suit the current study. To measure OTT viewing choice deferral, a mediating variable, we revised and applied measurement items from previous studies that examined users’ purchase delays in an online shopping environment (Cho et al., 2006). This scale was widely used to measure people’s difficulty in decision-making online. To measure OTT stress, a dependent variable, we modified and applied the questions of a study that measured social media stress to suit the OTT field (Lim et al., 2016). The OTT viewing choice deferral was divided into four questions, and the remaining variables included three questions each. All variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

Cronbach’s alpha was assessed using SPSS Version 27 to evaluate the reliability of the variables in the final model. This study employed AMOS for structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypothesized relationships among variables, including mediating effects. SEM was chosen for its ability to simultaneously examine complex relationships among multiple variables, making it particularly suitable for this study’s multidimensional framework involving content overload, social capital, affective ambivalence, choice deferral, and stress. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, both meeting the recommended thresholds (α > .70, CR > .70). Validity was ensured through discriminant validity, verified via the Fornell-Larcker criterion, and convergent validity, confirmed through factor loadings above .60 in the CFA. These analyses demonstrate the robustness of the measurement model and its alignment with the study’s objectives.

Results

This study verified the variables’ discriminant and convergent validity. The correlation between variables was identified through discriminant validity verification, and for this purpose, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied such that the square of the correlation coefficient between the two variables was smaller than the AVE coefficient (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The analysis showed that all the coefficients met the criteria (see Table 2). Next, construction reliability was verified, and it was confirmed that the reliability coefficient for all variables was above the standard value of .70 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Thus, it was proven that internal consistency exists between the items included as potential variables.

Next, to verify convergent validity, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the observation variables included in the latent variable (see Table 3). In general, the factor loading should be at least .50, and at least .70 is considered desirable (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Most factor loads were found to be .60 or more. The observational variables used in this study met the criteria for concentrated validity.

Structural Model

This study verified the fit of the research model using the absolute suitability index (χ2/df, RMSEA), incremental suitability indices (CFI, TLI), and the simplified suitability index (AGFI). As a result, it was found that most of them exceeded the standard or were close to it (see Table 4).

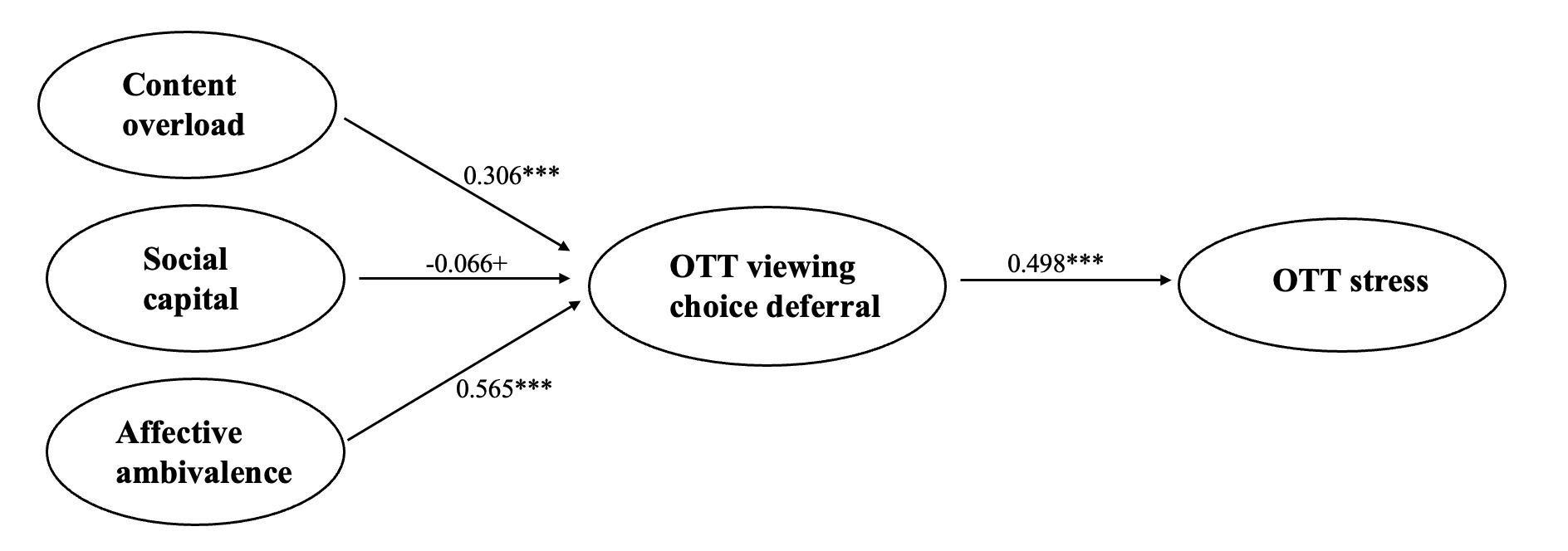

Next, hypothesis verification was conducted through structural model analysis. Figure 2 presents the path-coefficients (β) and their levels of significance. Content overload has been shown to have a positive effect on OTT viewing choice deferral, and H1 was supported (β = .305, p < .001). Next, social capital was found to have a negative and significant effect on OTT viewing choice deferral, and H2 was also supported (β = -.064, p < .088). Regarding H3, affective ambivalence had a positive effect on OTT viewing choice deferral, which suggested that H3 was supported (β = .591, p < .001). Finally, OTT viewing choice deferral was found to have a statically significant effect on OTT stress, and H4 was also supported (β = .624, p < .001).The variable with the highest explanatory power in OTT viewing choice deferral was affective ambivalence (β = .591), followed by content overload (β = .305). The explanatory power of social capital was confirmed to be the lowest level (β = -.064).

Discussion

Prior research has primarily examined the relationship between choice delay and negative psychological effects in the context of commodity consumption (Cho et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2018). This study, however, is the first to identify that a similar issue arises in the context of media use, marking a significant finding. Also, there was a research gap in media research regarding content choice deferral. While the literature addressing the effects of streaming media has often focused on the negative effects of binge-watching, our study highlights that decision-making deferral when selecting content can also trigger negative emotions.

The theoretical contribution of this study is that we try to reveal three key factors influencing choice deferral in the OTT domain that have been shown to have a significant impact in our research. Our results illustrate the relationship between content overload and choice deferral in OTT, contributing to the existing literature of choice overload and decision making. These results may also be explained by OTT market factors and have important practical implications. Competition among Korean domestic and foreign OTT companies, such as Netflix, TVing, and Watcha, is intensifying. More than half of the users subscribe to more than two OTT services. Therefore, from the perspective of OTT operators, it is necessary to provide content information that cannot be controlled by individuals to reduce deferral in user choices. In the paradox of choice theory, users hesitate to make the “best choice” when using content; thus, if operators provide recommended content by day of the week and list of content by ranking, they will achieve significant results in securing subscribers. Netflix provides a service that informs users of the release date of the content in advance and a function to delete the list of content selected by the user. Similarly, practitioners must devise measures to overcome viewing deferral by reducing users’ content choice.

Next, our findings contribute to the literature by demonstrating that the information benefits of social capital can help alleviate the problem of OTT choice deferral. Broad social capital resources can help viewers get more cues about what to watch and reduce the likelihood of choice deferral. Therefore, it is necessary to consider ways for OTT operators to lead community communication to resolve choice deferral. Expanding the function of sharing content with others or conducting content marketing in connection with SNS such as Facebook and Instagram is also worth considering.

In addition, the finding that affective ambivalence affects choice deferral can provide empirical support for the theory of affective ambivalence. Affective ambivalence theory states that a mixture of positive and negative emotions leads to increased complexity in individual decision making, which in turn may lead to delayed decision making. By validating this theory on OTT content selection, this study reinforces the applicability of this psychological mechanism in the realm of digital media consumption. Future research can further expand the influencing factors of OTT platform choice deferral to gain a more comprehensive understanding. In addition to content overload, social capital, and affective ambivalence mentioned in this study, user interface design and recommendation algorithms, perfectionism, and other individual personality traits may also be factors influencing choice delays on OTT platforms.

In response to a call to increase our understanding of the mechanism of how choice delay influences negative affect (Van Harreveld et al., 2015), the present research provides evidence that delays in decision making can increase negative psychological outcome-related stress. Therefore, strategic measures are required to reduce users’ choice deferral. At the same time, it is necessary to remember that although content is generally seen as entertaining and interesting, stress can arise from choice deferral. If stress persists, viewers might stop watching content as antipathy towards OTT services builds, potentially leading to the spread of negative information about the service to other users. Therefore, operators should reduce users’ content selection time or provide detailed information so that their psychological state can remain positive. In the current study, we focused on exploring how choice deferral can trigger psychological problems, such as stress. However, future research can further expand this area to understand whether choice deferral affect viewing behavioral decisions, such as abandoning a viewing or canceling a subscription due to selection delays. Future studies could also explore the impact of choice deferral on user experience, satisfaction, and individual differences in decision-making.

The results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies on user characteristics and stress. This means that OTT operators should not only provide user-based information, playability, and recommendation algorithms but also consider their social and psychological variables together to resolve choice deferral. For example, Netflix systematically organizes popular content by genre and provides it to its users. However, it is difficult to attract subscribers simply by providing good content. In other words, OTT operators must come up with a more detailed solution on what content to use and how to deploy it, along with content quality. This study confirmed that exposure to high-quality content in OTT services can cause choice deferral and further stress depending on users’ excessive recognition of content. The placement of content in the service, provision and sharing of information, and activation of the community are expected to be meaningful references in reducing users’ service satisfaction and choice deferral.

Previous studies have not thoroughly analyzed the relationship between OTT usage, choice deferral, and stress. This study revealed that prolonged decision-making during media content selection can increase users’ stress levels. Therefore, this research is significant in that it empirically examines the relationship between the options provided by OTT services and users’ psychological states and behaviors.

Conclusions

This study revised the concept of choice deferral, which has been used in consumer behavior and online shopping research and applied it to the OTT area. It is particularly meaningful because it explored the explanatory factors that affect OTT viewing choice deferral and confirmed that choice deferral in OTT services can cause mental problems. It also confirmed the significance of content overload, social capital, and affective ambivalence as determinants of OTT viewing choice deferral and found that OTT viewing choice deferral can negatively affect OTT users’ psychology. The analysis results are summarized as follows.

First, regarding H1, OTT content overload was proven to positively affect choice deferral when using OTT platforms. As explained by Netflix syndrome, this study confirmed that when users are in a situation with a significant amount of content to watch, they spend a considerable amount of time thinking and hesitating about what to watch. This is in line with previous studies (Kukar-Kinney & Close, 2010) showing that online shopping users delay purchasing products when faced with an overload of shopping information. The paradox of choice, which states that users can make bad decisions if they are given many options rather than fewer options, has also been confirmed. This can be explained by rational choice theory, which says that when choices increase, information overload leads to difficulties for users in gathering appropriate information to help make decisions, which increases the standard of acceptable decisions and the guilt associated with making the wrong decision (Schwartz et al., 2002); therefore, users are likely to delay making decisions.

Second, higher levels of social capital can help mitigate OTT choice deferral, indicating that frequent social activities may help users collect more choice-related cues and information, helping OTT users make choices faster and reducing choice-deferral problems. These results are consistent with those of previous studies on sharing various types of information and finding optimal alternatives (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000) due to the strong network of users. This result is interpreted as the result of social capital efficiently leading to human social participation based on social structures such as networks, trust, and norms (Putnam, 1993). Previous studies have indicated that social capital influences career and venture (Flap & Boxman, 2001), health (Mohnen et al., 2015), and daily life-related decisions (Johnson, 2007), and our study further reveals that social capital also has a positive impact on media content selection.

Third, this study confirmed that the higher the level of internal conflict or indecision experienced in the content selection situation, the more likely one is to defer a decision when selecting content. Affective ambivalence is the emotional instability experienced by individuals, which can have a positive effect on choice deferral. This is in line with consumer-related studies showing emotional equity in deferring product purchases (Huang et al., 2018). If users are indecisive about what content to watch when using OTT services, they can choose deferral. Since negative thoughts and beliefs cause internal tension (Mongraine & Vettese, 2003), suppressing them can be an alternative to reducing OTT systems’ choice deferral.

Finally, the higher the level of OTT viewing choice deferral, the higher the possibility of experiencing stress during OTT use. These results align with the existing discussion that delayed behavior can cause psychological instability in users (Burka & Yuen, 1983), and scholars believe that stress can have negative consequences on life satisfaction (Meyer et al., 2021). Our study confirms that choice deferral while using an OTT service may trigger psychological problems such as stress.

Limitations

First, our sample was collected over a relatively short period of time, although it was conducted through a specialized sample collection company. Additionally, since the sampling methodology was non-probability based, the results may not be fully generalizable to the broader population. The shorter data collection period may result in an under representative sample that may not capture potential changes and fluctuations over time, which may affect the generalizability of the findings of this study. Additionally, this study has limitations in verifying the extent to which users’ perceptions of OTT content influence actual stress levels. Future research should extend the data collection period and explore the relationship between the selection of specific content genres and stress induction. Second, our social capital measure focused on offline activities and did not adequately account for online social interactions and online relationships. This limitation is particularly significant in today’s digital society, as more and more people tend to obtain information from the Internet. Future research should more closely consider online social activities and virtual social networks when exploring the mitigating effects of social capital on OTT media content choice delays. Third, this study did not include an analysis of the mediating effect of OTT choice deferral, which could potentially help us better understand the mechanisms and pathways linking independent and dependent variables. This omission stems from the inability to establish a direct relationship between these variables based on the limited number of previous studies in this domain. A subsequent analysis was conducted to assess the direct impact of independent variables on OTT stress. The findings indicated that only affective ambivalence directly affect OTT stress (β = .486, p < .001), while information overload and social capital do not demonstrate a significant direct effect on OTT stress. These results underscore the need for more comprehensive future research to unravel the intricate interplay among these variables.