The social control perspective on public opinion dominates the literature on the spiral of silence (SOS) theory. It argues that a majority “institutionalize(s) consensus” (Scheufle & Moy, 2000, p. 5) by imposing social sanctions on individuals who express a minority view. Individuals moderate their opinions to avoid angering the majority and win its approval. This perspective limits the role of individuals in expressing opinions, as they are subject to external pressure.

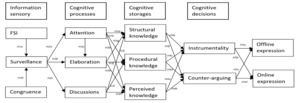

The current study presents a rational perspective on the SOS, which emphasizes the agency of individuals who instrumentally consume information to permit them to debate issues wisely (Scheufle & Moy, 2000). Individuals’ decisions about speaking out are internally determined by their knowledge and their efforts to process information. To this end, this study adopts the cognitive-mediation model (CMM) of Eveland (2001, 2002) to predict opinion expression. Opinion expression is the main behavioral output in SOS. Like the rational perspective on SOS, CMM emphasizes the role of audience members who (1) are motivated to seek media messages that they (2) pay attention to in order to (3) cognitively elaborate and (4) learn.

Accordingly, this study first introduces a rational perspective on opinion expression that is internally-driven by individuals’ cognitive internalization of information. This perspective is contrasted with the social control perspective with its mechanisms of fear of social isolation (FSI) and opinion congruency that control expressions of opinion. This study also contributes to the CMM literature in various ways. It explores the way cognitive activities (cognitive elaboration, interpersonal discussions, and attention to news media) influence the acquisition of procedural knowledge, perceived familiarity, and structural knowledge. These are forms of knowledge that previous CMM studies have explored (e.g. Eveland & Schmitt, 2015; Yang et al., 2017). While perceived familiarity refers to general factual knowledge about an issue (Yang et al., 2017), and structural knowledge refers to connecting an issue to other issues to reach conclusions (Eveland & Schmitt, 2015), procedural knowledge refers to applying knowledge in problem-solution situations (Burgin, 2017). In relation to opinion expression, it is proposed that individuals who have knowledge about an issue will be more communicative of their opinions about it, since they are under the impression they know how to resolve the problems related to the issue.

A further contribution of our study is the introduction of a cognitive-decisional stage to CMM. Previous CMM studies have either explored cognitive activities as a means to learning from media news as the final output of CMM (e.g. Jensen et al., 2020) or explored the ways that learning from news results in the prediction of behaviors as the final output of CMM (e.g. Jiang et al., 2021; T. H. Zhang et al., 2024). The current study proposes a new stage, cognitive decision, inserted between retained knowledge and opinion expression, the latter being the behavioral output this study examines. Before speaking out, individuals weigh their confidence and certainty about their retained knowledge, and judge whether it is conducive to opinion expression (information instrumentality). Also, individuals assess their ability to refute the arguments of others by assessing an argument’s validity, flawlessness, and consistency (counter-arguing) (Fransen et al., 2015). Such cognitive decisions place individuals in a better position to decide whether to speak or not.

Previous CMM studies have tested the model in relation to various behaviors, such as cancer screening intention (T. H. Zhang et al., 2024), engagement in social media (Guo & Chen, 2022), use of online fitness applications (Jiang et al., 2021), conducting breast cancer examinations (L. Zhang & Yang, 2021), and intention to receive the HPV vaccine (Li & Bautista, 2021). The current study explores CMM in relation to the opinion expression concept of SOS. While previous CMM studies have mainly explored personally-driven behaviors, where individuals undertook such behaviors in isolation from others, opinion expression is a social behavior that triggers interaction with others. Such behavior is subject to the evaluation and social sanctions of others, according to SOS, and is more intense and emotionally demanding. This presents a serious test for CMM in dire situations. Finally, previous CMM studies (e.g. Li & Bautista, 2021; L. Zhang & Yang, 2021) have mainly explored the model in offline contexts. The current study explores it in relation to offline and online opinion expression.

Social Context and Issues of Research Exploration

The State of Kuwait represents the socio-political context in which this study took place. Kuwait is located by the Arab Gulf and is bordered by Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The political system of this state of 5 million people is a constitutional monarchy, and oil contributes to its economic wealth (CIA Factbook: Kuwait, 2024). Since Kuwait is a collectivist society, its context will be ideal for testing a rational perspective on opinion expression. Previous SOS studies in Kuwait (Al-Kandari et al., 2022; Al-Sumait et al., 2021) confirm the strong influence of FSI and opinion congruency on the opinion expression of individuals. This study will explore how individuals’ personal cognitive internalization can withstand the social control mechanisms suggested by SOS.

Hong and Li (2022) argue that a spiral of silence process functions well when issues are controversial and divide public opinion. Also, an SOS examined issue has to have a moral component (value-laden) in which FSI is more likely to materialize. It is the moral element that makes public opinion exert its power to isolate individuals who have deviant opinions from that of the majority (Hong & Li, 2022). In order to test the model, this study employs two samples of individuals responding to questionnaires assessing two different issues that are controversial and ethical in nature. In one sample, respondents were asked about the issue of dual-nationality, and in the other sample about women’s freedoms.

There are estimated to be 400,000 dual-national citizens in Kuwait (CIA Factbook: Kuwait, 2024). This issue has been controversial, and the moral issues have been debated in the press, social media, and Kuwait’s national parliament in relation to national security, the economy, education, and culture. For example, some Kuwaitis argue that dual-nationality is a global phenomenon and that almost all societies have citizens who hold dual-nationality. Others, from a national security standpoint, question the loyalty of those individuals with dual-nationality. They argue that during wartime or traumatic times, the position of those individuals may be unsympathetic or uncaring to Kuwait as they can leave the country during those demanding situations (Aljarallah & Alrasheed, 2021). Moral judgement is an obvious feature of this issue.

Similarly, issues of women’s freedom have been controversial and value-laden and have been widely discussed by people on social media and at social gatherings. Such freedoms include the liberty for women to act in different ways, such as voluntarily removing the Hijab, traveling alone or with friends without the company of male family members, and other similar behaviors that liberate Middle Eastern women from the conservative culture and religious restrictions. Strobl (2010) argues that women’s issues represent a controversy and divide traditionalists and liberals. Such issues provoke moral debate because they are subject to Arab cultural and religious moral judgements. Even in the religious community, religious moderates suggest that Islam gives women total freedom to decide about when and where to travel. However, conservatives argue that women have to have a male first degree relative (i.e., father, brother, husband, or son) to accompany them when traveling (Nukbah, 2023).

A Proposed Model for CMM and SOS

As shown in Figure 1, the model employed in this study starts with (1) SOS components that (2) motivate individuals to seek information in order to discern the prevalence of public opinion on issues. When individuals acquire information, they (3) cognitively process them. Some processed information is (4) stored in memory as knowledge. Finally, individuals (5) cognitively assess their knowledge to make decisions about speaking out in conversational contexts.

This study’s model starts with SOS theoretical mechanisms. The SOS process begins when a group of individuals perceive that their opinion on a public matter represents a minority view. This group of individuals fear social isolation (FSI) in the case that they express their minority view in the face of a majority that embraces the other view. This fear causes the holders of the minority view to refrain from expressing themselves, to avoid social isolation. This leads other people who hold the same minority view to further refrain from expressing their view when they see that their minority view is withdrawing from public discourse. This gradual withdrawal of the minority opinion causes the spiral of silence to expand (Noelle-Neumann & Petersen, 2004). In this SOS process, FSI triggers individuals to survey news media to perceive the socially acceptable views that they can speak about (Hayes et al., 2013).

Noelle-Neumann and Petersen (2004) speak about opinion congruence as another SOS mechanism that regulates individuals’ expression of opinions. Perceiving a personal opinion to be congruent with the majority opinion encourages people to express this opinion. To avoid FSI and better assess the congruence of opinions, individuals detect public opinion “to see which opinions and modes will win the approval of society and which will lead to their isolation” (Noelle-Neumann, 1995, p. 42). Since media are important means of detecting the standing of public opinion, people turn to them.

Eveland (2001, 2002) employs the uses and gratifications perspective to determine people’s motivations for using media news. Eveland focused on the surveillance motive, which is the act of seeking out information “about some feature of society and the wider world” (Blumler, 1979, p. 17). Eveland (2001) argues that a number of uses and gratifications studies have failed to detect direct links between surveillance and knowledge acquisition from media. He therefore argues that surveillance “should have an indirect effect on learning through the information processing behaviors they instigate” (Eveland, 2001, p. 572). Media surveillance brings information to a person’s cognition for processing and eventual learning.

The surveillance motive does not suffice to generate learning from media (Eveland, 2001); “Whether or not one intends to learn really does not matter. What matters is how one processes the material during its presentation” (Anderson, 1980; p. 197). Therefore, Eveland (2001) notes that the uses and gratifications literature indicates “two types of information processing—attention and elaboration—should be employed by those who seek surveillance gratifications” for learning to happen (p. 576). Attention is the mental concentration given to a media message, and elaboration is the thinking style that mnemonically connects, through cognitive retrieval, new information on an issue to older information stored in memory. Eveland (2001) argues that attention is more effective in explaining variance in media effects than mere exposure to media content. Elaboration induces learning by connecting connotative and associative meanings to the information obtained and generating inferences from that information (Eveland, 2002).

Interpersonal discussions is an additional cognitive process this study explores. It is a form of collective elaboration and “a reasoning behavior because exchanging opinions inherently entails mental elaboration” (Jung et al., 2011, p. 409). Deliberations of individuals in interpersonal discussions instigate a collective integrative reflection through which individuals weigh an opinion’s pros and cons, grasp topics, process complex concepts, and draw logical inferences and conclusions (Jung et al., 2011; T. H. Zhang et al., 2024). This process also leads to gaining knowledge (T. H. Zhang et al., 2024).

The final stage in Eveland’s CMM is learning, which he defines as the “general act of movement or manipulation of information in memory” (Eveland, 2002, p. 28). Scholars divide learning into three knowledge dimensions: factual, procedural, and structural knowledge (Lee et al., 2016). Factual knowledge consists of the facts, historical accounts, and background of an issue. Procedural knowledge refers to the ability to apply knowledge in problem solving. Structural knowledge indicates the level of relatedness between an issue and other issues. While factual knowledge represents different mental information nodes, structural knowledge represents the linkages between those nodes (e.g. relating a political issue to economics).

Eveland (2011) operationalized learning as the factual knowledge a person gains. Yang et al. (2017) employed perceived familiarity as an alternative indicator of learning. Findahl (2001) argues, “The fact that so little specific information can be remembered from a news story does not mean that no learning takes place. The informative base from which conclusions are drawn can be forgotten while the conclusions remain” (p. 119). The present study employs perceived familiarity because it stays longer in memory. This study also uses procedural knowledge because individuals who gain such knowledge develop deep understanding. Those who propose solutions to problems go beyond knowing basic facts and background. They know the different nuances affecting the problem and the solutions that may or may not work (Burgin, 2017). Our study also employs structural knowledge because studies indicate that individuals who link multiple lines of information and news stories together develop a cognitive complexity (Eveland & Schmitt, 2015) that generates a variety of justifications and rationales (Brundidge, 2010) for effective use in expressing viewpoints (Al-Kandari et al., 2022).

This study advances Eveland’s CMM by incorporating cognitive aspects of decisions into this model. This study argues that people do not arbitrarily and hastily enter conversations. They assess their knowledge in relation to two aspects that help them in making decisions about speaking out about a topic. First, information instrumentality is a personal level of certainty and confidence about the information an individual has to support expressing an opinion. Past research examines similar concepts, such as political efficacy and political information efficacy (Oh et al., 2021). Those concepts, which refer to the level of self-confidence in personal abilities and knowledge, were found to predict social and political behaviors (Oh et al., 2021). The second decision aspect is counter-arguing. A person evaluates persuasive messages, comparing them with arguments that refute them and assesses each argument’s degree of validity, flawlessness, and consistency. Research indicates that individuals who resist persuasive messages usually produce counter-argument strategies and tactics in order to immunize their attitudes and neutralize the effects of persuasive messages (Fransen et al., 2015).

Recent studies have advanced CMM by examining its influence on people’s behaviors, specifically in offline situations (e.g. Guo & Chen, 2022; Jiang et al., 2021). Our study advances CMM by exploring it in relation to SOS’s main output concept of opinion expression in offline and online settings. Opinion expression is a social behavior rather than a personal behavior, taken in isolation. The intensity of undertaking a social behavior is greater as it is more often subject to the evaluation, criticism, and social sanctions of others.

While there is ample SOS literature on offline settings, the SOS online literature is modest by comparison. To relate this study’s objective to SOS’s online expressions, four perspectives on online opinion expression are discussed (Al-Sumait et al., 2021). First, the “cyber optimist” perspective argues that online media increase the likelihood of opinion expression because there are specific online media factors that free individuals from the discomfort of standing alone in the face of a majority and its social repression. Those factors are online anonymity, lack of social cues and social pressures in online settings, and availability of like-minded people in online networks. The “online lurking” perspective suggests that online media are not conducive to opinion expression because the majority of online media users passively go online to read and observe opinions rather than interact and discuss. The “neutral online” perspective suggests that online environments are objective conduits that only reflect the true offline nature and identity of individuals. People who by their nature are expressive or inexpressive of opinions offline will remain the same online. Finally, the “online enculturation” perspective argues that online settings form their own unique virtual cultural dynamics and socialization conventions that affect opinion expression. For example, people who follow specific online groups or accounts for reinforcement purposes come to the conclusion that they have a supportive opinion climate that in turn increases their likelihood of expressing opinions.

Hypotheses

SOS

FSI

To avoid expressing deviant opinions that cause social ostracism, people “try to find out which opinions and modes of behavior are prevalent”. They “constantly observe their environment very closely” (Noelle-Neumann, 1977, p. 144) because “the effort spent in observing the environment is apparently a smaller price to pay than the risk of losing the goodwill of one’s fellow human beings—of becoming rejected, despised, alone” (Noelle-Neumann, 1993, p. 41). Hayes et al. (2013) confirmed this conclusion in their study of eight nations and found that FSI triggered people to seek information to assess “what the public thinks” (p. 404).

Opinion Congruency

Noelle-Neumann (1977) argues, “Individuals who, when observing their environments, notice that their own personal opinion is spreading and is taken over by others, will voice this opinion self-confidently in public. On the other hand, individuals who notice that their own opinions are losing ground, will be inclined to adopt a more reserved attitude when expressing their opinions in public (p. 144).” Accordingly, individuals consume media information to ascertain if their opinions are still on “the rise” to continue speaking out unreservedly or “losing ground” to be less forthcoming about expressing their opinions.

Based on the previous discussion, the following hypotheses are posited:

H1a: FSI will predict the motivation of individuals for media surveillance.

H1b: Opinion congruence will predict the motivation of individuals for media surveillance.

Information Inputs

Surveillance

People update their cognitive awareness system with media news and information according to the perceived accuracy of the news. People perceive the news as a reflection of reality that impacts aspects of their daily life. To know the events’ impact on their life and ways to react (Bennett, 2016), people integrate media information into their cognitive decision-making system. This integration is a prolonged process that starts with paying attention to media messages. When paying attention to messages, people reduce cognitive interference to clear a cognitive space for receiving message details. Then, they regulate cognition to concentrate on messages and aspects that lead to a greater mental processing.

Because media information content consists of more complex cues than other media content, processing information requires greater attention to process sufficiently for understanding (Guo & Chen, 2022). Eveland (2002) argues, “Surveillance gratifications-seeking should lead those who expose themselves to the news media to pay greater attention and process the content more deeply than those who do not endorse surveillance gratifications” (p. 22).

Since elaboration is the process of thinking of new news and information in conjunction with information already stored in memory, a greater reception of information means making more information available for cognitive elaboration by retrieval of stored information from memory (Jensen et al., 2020; Li & Bautista, 2021).

Finally, individuals who have more information about an issue engage in discussions with others about that issue because they know things to say. Research confirms this fact. People who expect to participate in future conversations frequently consume media information to use in conversations (Al-Kandari et al., 2022; L. Zhang & Yang, 2021).

Based on the previous literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a: The media surveillance motivation will predict individuals’ attention to media messages.

H2b: The media surveillance motivation will predict individuals’ cognitive elaboration of media messages.

H2c: The media surveillance motivation will predict individuals’ interpersonal discussions of issues.

Cognitive processing activities

Attention

Research confirms that attention leads to more cognitive elaboration (Li & Bautista, 2021; Yang et al., 2023). When individuals pay closer attention to messages, they grasp many of their details and features. This forces cognition to actively retrieve stored information for elaboration with the new incoming details and features.

For many reasons, paying attention makes people knowledgeable about an issue (e.g. Jensen et al., 2020; Li & Bautista, 2021) even if they do not elaborate on it. First, paying attention results in an automatic storing of information with little or no elaboration if incoming information is repetitive or has few new details. Second, cognition stores information directly, with little or no elaboration, and when cognition reaches saturation, there is a feeling that further elaboration about a topic is unnecessary. Finally, people who already endorse an attitude or have made up their mind about an issue elaborate new information very little because they store information that enhances cognitive consistency and reinforces attitudes.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: Attention to media messages will predict cognitive elaboration.

H3b: Individuals’ attention to media messages will predict perceived familiarity.

H3c: Individuals’ attention to media messages will predict procedural knowledge.

H3d: Individuals’ attention to media messages will predict structural knowledge.

Elaboration

People need to elaborate media messages to comprehend the messages and make decisions about what impacts them and their community (Bennett, 2016). The more information people receive about an issue, the more they elaborate, which helps in constructing a “cognitive framework for acquiring and processing additional information” (Clarke & Fredin, 1978, p. 145). This cognitive framework enhances knowledge acquisition by facilitating storage where additional information can be stored in memory quickly. The frequent exercise of elaboration extends and expands mental pathways in the cognitive framework for storing information (Eveland, 2001). Recent CMM research confirms that elaboration leads to gaining knowledge (Jiang, 2024; L. Zhang & Yang, 2021).

In the light of the previous review, the following hypotheses are posited:

H3e: Cognitive elaboration will predict perceived knowledge.

H3f: Cognitive elaboration will predict procedural knowledge.

H3g: Cognitive elaboration will predict structural knowledge.

Interpersonal Discussions

In discussion contexts, people do not often have the privilege of selective exposure as they have when using media. Therefore, their possibility of exposure to new information and different perspectives will be higher, which enhances their knowledge of various facets of an issue. In addition, interpersonal discussions represent a collective form of elaboration. People who listen to information from others elaborate them with the information they retain in memory. This also enhances knowledge (Lee et al., 2016; T. H. Zhang et al., 2024).

As a result, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3h: Interpersonal discussions about an issue will predict individuals’ perceived familiarity.

H3i: Interpersonal discussions about an issue will predict individuals’ procedural knowledge.

H3j: Interpersonal discussions about an issue will predict individuals’ structural knowledge.

Cognitive Storage

Perceived Familiarity

People with more knowledge about an issue will believe their information supports their expression of opinion. Research indicates that people who are knowledgeable about an issue frequently engage in reflection and deliberation about it (Ziegele et al., 2020). This in turn enables them to produce more arguments and justifications that they can utilize in sharing opinions (Al-Kandari et al., 2022).

Also, a greater perceived familiarity with a topic enables a cognitive critical and analytical assessment of the faults and weaknesses of other people’s viewpoints. Booth-Butterfield and Welbourne (2002) state that, “High levels of knowledge about a topic encourage greater elaboration on a persuasive message pertaining to that topic. Conversely, if a person has very little knowledge about a topic, thoughtful scrutiny of the arguments in a message might not be possible” (p. 160).

Procedural Knowledge

People who retain a detailed and deep understanding of a problematic issue can go beyond knowing its facts to propose ways of resolving it. Those people experience an issue firsthand and observe its impact on people in their social circles. The result is a greater emotional involvement that makes them think about the issue’s various aspects and ways of responding (Burgin, 2017). With such emotional involvement in and knowledge about an issue, people feel their information is instrumental for an opinion exchange.

In addition, people who gain procedural knowledge understand an issue’s different nuances because they hear different perspectives about it. Gaining diverse knowledge leads to knowing why certain solutions may or may not work. This forms critical knowledge that produces counterarguments.

Structural Knowledge

People who tie multiple lines of information and news together develop cognitive complexity and cognitive maps (Eveland & Schmitt, 2015) that can generate rationales, justifications, and sophisticated reasoning (Brundidge, 2010) that they can use to supplement their opinions (Al-Kandari et al., 2022).

Also, people with structural knowledge are more likely to counter-argue and dispute what others express. Exposure to complex messages that connect different issues together enables viewers to unpack flaws and inconsistencies in different perspectives and develop counterarguments (Polk et al., 2009). Also, evaluating an issue’s different aspects contributes to structural knowledge that people use to defend their views (Petty et al., 2014).

Based on the previous literature, the following hypotheses are posited:

H4a: Perceived familiarity will predict individuals’ information instrumentality.

H4b: Perceived familiarity will predict individuals’ counter-arguing.

H4c: Procedural knowledge will predict individuals’ information instrumentality.

H4d: Procedural knowledge will predict individuals’ counter-arguing.

H4e: Structural knowledge will predict individuals’ information instrumentality.

H4f: Structural knowledge will predict individuals’ counter-arguing.

Cognitive Decision

Information Instrumentality

For various reasons, it is expected that instrumentality will predict opinion expression offline and online. First, people with more knowledge engage in discussions with others (Al-Kandari et al., 2022) because they believe they know about an issue more than others, which makes them feel confident to exchange opinions (Lee et al., 2016). Second, the amount of retained information induces cognitive reflection and deliberation (Al-Kandari et al., 2022) that generates complex conclusions, arguments, and sophisticated rationales (Brundidge, 2010; Eveland & Schmitt, 2015) that individuals can use in conversations. Third, people who frequently follow news media to learn about the news also learn arguments they can use in conversations. Eveland et al. (2001) discuss “knowledge in use” and Noelle-Neumann (1993) discusses the “articulation function” of media, referring to the communication styles people learn from media and can use to articulate their own arguments.

Counter-Arguing

For different reasons, individuals who counter-argue will feel more self-assured about their ability to exchange opinions. First, those who inspect other’s arguments to find their flaws and contradictions indirectly reinforce their own attitudes as morally correct and deserving of protection and defense in conversation. Second, individuals who tend to counter-argue eventually become equipped with critical and analytical skills that make them less inclined to accept opposing opinions and this triggers them to counter other arguments in conversation. Third, people who retain many counterarguments will feel secure that they can prevail in conversation. In one study, Meirick (2002) found that people who generated counter-arguments contested others’ arguments more often than those who generated fewer counter-arguments. Another study found that those who thought of an issue in order to generate counter-arguments against it were more likely to speak out against it in conversation (Lin, 2022).

Given the previous review of the literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a: Controlling for demographics, information instrumentality will predict opinion expression in an offline setting.

H5b: Controlling for demographics, counter-arguing will predict opinion expression in an offline setting.

H5c: Controlling for demographics, information instrumentality will predict opinion expression in an online setting.

H5d: Controlling for demographics, counter-arguing will predict opinion expression in an online setting.

Methods

Sampling Procedures

For both samples, two sampling techniques were employed to attain a representative sample. First, a simple random sampling technique based on university identification numbers was employed at two universities in Kuwait to recruit students who would later participate in a network sampling technique. The sampling frame was initially set to randomly select 1,000 students from each university to participate in questionnaire distribution. This large number was determined to account for those who might decline participation. Selected students were emailed, and the email provided a full description and instructions on the entire process. To secure a target of at least 1,000 respondents for each sample, the researchers kept recruiting and emailing new randomly selected students. Of all contacted students (Sample 1 = 2,000, Sample 2 = 3,000), 187 (response rate = 9%) students actually participated in the first sample and 218 (response rate = 7%) participated in the second.

For the network sample, the students administered the questionnaire to first-degree family members (father, mother, and siblings). They were instructed to allow family members aged 18 years and over to participate in the questionnaire. In Kuwait, the culturally Arab and Muslim conservative state, surveying respondents from the opposite gender is difficult. Allowing students to administer the questionnaire in a network sample overcomes this cultural difficulty (Cohen & Arieli, 2011). On average, a student was able to secure the response of 5-6 respondents. This average number reflects the size of the collective and traditional Kuwaiti family (Wang, 2023).

One-thousand-fifty respondents answered the questionnaire about dual-nationality and 1,289 answered the one about women’s freedoms. These sample sizes from a country of five million people are adequate. Of the 1,050 respondents in the first sample, 546 were male (53%) and 484 (47%) were female. Also, 448 (42%) were aged 18 to 25, 226 (22%) 26 to 33, 165 (16%) 34 to 43, 153 (15%) 44 to 55, and 51 (5%) were more than 55 years of age. In the second sample, 526 (41%) were male and 754 (59%) were female; 485 (38%) were aged 18 to 25, 289 (22%) 26 to 33, 188 (15%) 34 to 43, 206 (16%) 44 to 55, and 112 (9%) were at the age of 56 or more.

Predictor Variables

FSI

The FSI index was adopted from Al-Kandari et al. (2022). The items were, “I worry about being isolated if people disagree with me,” “I avoid telling other people what I think when there is a risk that they will avoid me if they know my opinion,” and “I feel annoyed if nobody wants to be around me because of my personal opinions.” Respondents responded on a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .885, M = 2.5, SD = 1.3; Study 2: α = .909, M = 2.5, SD = 1.2).

Opinion Congruence

From Matthes (2015) an index of two items was used. The items were: “My opinion about (issue) is similar to the opinion of the majority of people in our society” and “I have a similar opinion regarding (issue) to most people in our society.” Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .881, M = 3.5, SD = 1.2; Study 2: α = .949, M = 3.1, SD = 1.1).

Mediator Variables

Surveillance

Surveillance was developed using three items. They were, “I often search for information about (issue),” “When I hear or see a news story about (issue), I go online to read more about it,” and “I very much seek information about (issue) to know more about it.” Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .906, M = 3.0, SD = 1.2; Study 2: α = .927, M = 3.2, SD = 1.1).

Attention

Attention included two items: “How much focus do you give to news and information about (issue)?” and “How much attention do you pay to news and information about (issue)?” Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale (5 = high focus/attention, 1 = low focus/attention) (Study 1: α = .934, M = 2.9, SD = 1.3; Study 2: α = .965, M = 3.2, SD = 1.1).

Elaboration

The measurement of elaboration was adopted from Eveland (2001). The items were: “I often think about the news I receive from media about (issue),” “I think about how what I receive from the media about the (issue) links to other things I know about this issue,” “I try to relate the news and information I receive from the media about the (issue) to my own past experiences,” and “I frequently link new news about the (issue) to my own prior personal experiences.” Respondents used a five-point scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .899, M = 3.288, SD = 1.1; Study 2: α = .913, M = 3.5, SD = 1.1).

Discussion

Discussion was measured using two items: “How much do you discuss the issue of (issue) with other people?” and “How much do you converse with others about the (issue)?” Responses were on 5-point scale (5 = very much, 1 = very little) (Study 1: α = .947, M = 2.7, SD = 1.2; Study 2: α = .945, M = 2.9, SD = 1.1).

Perceived Familiarity

This measure was adopted from Yang et al. (2017). Items were: “How familiar are you with about the (issue)?” “How much understanding do you have about all aspects surrounding the (issue)?” and “How much detail do you know about the (issue)?” Respondents used a 5-point scale (5 = very much, 1 = very little) (Study 1: α = .937, M = 3.0, SD = 1.1; Study 2: α = .937, M = 3.2, SD = 1.0).

Procedural Knowledge

We created different indices of items to assess procedural knowledge, structural knowledge, information instrumentality, and opinion expression. Initially, multiple statement items were written to reflect each concept. Then, the items were tested in a pilot study of 121 individuals who expressed their level of agreement with the statements using 5-point scales (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree). An index of items was employed in the final survey if it met the criteria of a Cronbach’s alpha score of .70 or above.

For procedural knowledge, the final survey items were: “I can think of many solutions that can reduce differences about the issue of (issue),” “I have solutions that can contribute to resolving challenges resulting from the issue of (issue),” and “I can think of many ways to diminish problems emerging from (issue).” Respondents used a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .911, M = 3.4, SD = 1.1; Study 2: α = .919, M = 3.4, SD = 1.0).

Structural Knowledge

This measure consisted of four items: “My knowledge about the (issue) is linked to other issues in the society,” “I am aware of the different impacts of the (issue) on the society,” “For me, (issue) is multifaceted and I cannot think of it in isolation from other issues in the society,” and “My understanding of (issue) relates it to various social and political aspects in our society.” Respondents used a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .779, M = 3.5, SD = 1.2; Study 2: α = .856, M = 3.5, SD = 1.0).

Information Instrumentality

This index consisted of three items: “To what extent do you trust that your information about the (issue) will enable you to convince others about your viewpoint in conversations about this issue?”, “To what extent are you certain that the information you know about the (issue) will benefit you in your discussions with others about this issue?”, and “To what extent do you trust that your knowledge about the (issue) will help you to exchange your opinions in conversations with others about this issue?”. Respondents used a 5-point scale (5 = very great extent, 1 = very little extent) (Study 1: α = .888, M = 3.3, SD = 1.2; Study 2: α = .934, M = 3.5, SD = 1.0).

Counter-Arguing

This measure was adopted from Moyer-Gusé et al. (2022). Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement to statements describing their reactions if they were in a conversation with people expressing opinions that differed from their own. The items were: “I find myself wanting to respond to what is being discussed,” “I find myself thinking that the discussants offer inaccurate information,” “I find myself looking for flaws in the way information is discussed,” and “I find myself wanting to correct what is being said.” Respondents used a 5-point scale (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) (Study 1: α = .832, M = 3.4, SD = 1.1; Study 2: α = .847, M = 3.4, SD = 1.1).

Criterion Variable

Opinion Expression

This variable was created from three responses. Respondents were asked to estimate their likelihood of getting involved in a social gathering’s discussion about the explored issues for the following reasons: “To express your opinion about the issue,” “To defend your view about the issue,” and “To convince others about your own opinion about the issue.” For expressing an opinion online, the respondents answered the same questions about getting into an online discussion about the explored issues. Respondents answered using a 5-point scale (5 = extremely likely, 1 = extremely unlikely) (Study 1: α = .904, M = 3.6, SD = 1.4; Study 2: α = .894, M = 3.7, SD = 1.2).

Results

Statistical Analyses

Two structural equation modeling (SEM) processes were performed for each sample using SmartPLS 4. Different statistical methods were employed to assess construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Calculating statistical significance for SEMs was achieved by calculating path coefficients of a 5000 resampled bootstrapping technique (Hair et al., 2021). Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR), while convergent and discriminant validity were confirmed through average variance extracted (AVE) and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Indicator loadings exceeding .70 further validated the constructs. The structural model was analyzed using path coefficients, t-statistics, and p-values, with model fit assessed via standardized root mean square residual (SRMR <.08). A bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples ensured robust results.

Study 1 (Dual-Nationality Issue)

Measurement Model

Construct Reliability. Values of composite reliability for each construct ranged from .78 to .95. They were higher than the acceptable threshold values of .70 (Hair et al., 2021) (Table 1).

Convergent Validity. Values of factor loading ranged from .65 to .94 and AVE from .54 to .90. Both met the acceptable threshold values of .60 for factor loading and .50 for AVE (Hair et al., 2021) (Table 1).

Discriminant Validity. For cross-loadings, indicators of each construct loaded higher than that of its corresponding construct. The Fornell-Larcker criterion was met because the square roots of all AVEs exceeded their correlations with other constructs. As for HTMT, none of the construct values exceeded the threshold value criterion of .85 (Hair et al., 2021).

Results

Statistics confirmed all hypotheses except one. The results indicated that FSI (H1a) (β = .27, t = 9.28, p < .001) and opinion congruence (H1b) (β = .19, t = 5.85, p < .001) predicted surveillance.

Also, surveillance predicted attention (H2a) (β = .49, t = 18.99, p < .001), elaboration (H2b) (β = .53, t = 19.91, p < .001) and discussions (H2c) (β = .47, t = 17.32, p < .001).

In addition, attention predicted elaboration (H3a) (β = .23, t = 8.16, p < .001), perceived familiarity (H3b) (β = .29, t = 7.80, p < .001), procedural knowledge, (H3c) (β = .16, t = 3.82, p < .001), and structural knowledge (H3d) (β = .22, t = 3.73, p < .001). Elaboration predicted perceived familiarity (H3e) (β = .09, t = 3.193, p = .001), procedural knowledge, (H3f) (β = .29, t = 7.91, p < .001), and structural knowledge (H3g) (β = .38, t = 8.90, p < .001). Discussions predicted perceived familiarity (H3h) (β = .45, t = 11.94, p < .001) and procedural knowledge (H3i) (β = .18, t = 4.37, p < .001) but failed to predict structural knowledge (H3j) (β = -.03, t = 0.44, p = .658).

Furthermore, perceived familiarity predicted instrumentality (H4a) (β = .51, t = 17.57, p < .001) and counter-arguing (H4b) (β = .17, t = 5.06, p < .001). Procedural knowledge predicted instrumentality (H4c) (β = 0.26, t = 9.04, p < .001) and counter-arguing (H4d) (β = 0.26, t = 6.71, p < .001). Structural knowledge predicted instrumentality (H4e) (β = .09, t = 4.03, p < .001) and counter-arguing (H4f) (β = .29, t = 8.48, p < .001).

Finally, instrumentality predicted opinion expression offline (H5a) (β = .35, t = 10.36, p < .001) and online (H5b) (β = .27, t = 8.11, p < .001) and counter-arguing predicted opinion expression offline (H5c) (β = .23, t = 6.83, p < .001) and online (H5d) (β = .13, t = 3.88, p < .001) (Figure 2; Table 2). After controlling demographics (gender and age), demographics did not have significant influence except for gender on instrumentality predicting opinion expression online (β = .23, t = 3.39, p < .001) and counter-arguing predicting opinion expression online too (β = -.15, t = 2.19, p = .029).

Study 2 (Women’s Freedoms Issue)

Measurement Model

Construct Reliability. Composite reliability values for all constructs ranged from .85 to .97. They were higher than the acceptable threshold value of .70 (Hair et al., 2021) (Table 1).

Convergent Validity. Factor loading values for all items ranged from .70 to .97 and AVE for all constructs ranged from .67 to .93. Both met the acceptable threshold values of .60 for factor loading and .50 for AVE (Hair et al., 2021) (Table 1).

Discriminant Validity. For cross-loadings, indicators of each construct loaded higher than that of its corresponding construct. The Fornell-Larcker criterion was achieved as the square roots of all AVEs surpassed their correlations with other constructs. As for HTMT, none of the construct values exceeded the threshold value criterion of .85 (Hair et al., 2021).

Results

The statistical analysis of Study 2 confirmed all hypotheses. The results indicated that FSI positively predicted surveillance (H1a) (β = .29, t = 10.67, p < .001) and opinion congruence (H1b) (β = -.09, t = 2.36, p < .001) negatively predicted surveillance.

Also, surveillance predicted attention (H2a) (β = .58, t = 28.27, p < .001), elaboration (H2b) (β = .43, t = 14.80, p < .001), and discussions (H2c) (β = .51, t = 23.77, p < .001).

Furthermore, attention predicted elaboration (H3a) (β = .27, t = 9.62, p < .001), perceived familiarity (H3b) (β = .33, t = 9.59, p < .001), procedural knowledge (H3c) (β = 0.18, t = 5.11, p < .001), and structural knowledge (H3d) (β = 0.18, t = 4.98, p < .001). Elaboration predicted perceived familiarity (H3e) (β = .09, t = 3.30, p < .001), procedural knowledge, (H3f) (β = .23, t = 7.63, p < .001), and structural knowledge (H3g) (β = .37, t = 11.37, p < .001). Discussions predicted perceived familiarity (H3h) (β = .34, t = 10.39, p < .001), procedural knowledge (H3i) (β = .24, t = 6.74, p = .001), and structural knowledge (H3j) (β = .07, t = 2.20, p = .028).

In addition, perceived familiarity predicted instrumentality (H4a) (β = .56, t = 22.00, p < .001) and counter-arguing (H4b) (β = .10, t = 3.34, p = .001). Procedural knowledge predicted instrumentality (H4c) (β = .16, t = 5.71, p < .001) and counter-arguing (H4d) (β = .23, t = 7.16, p < .001). Structural knowledge predicted instrumentality (H4e) (β = .08, t = 3.04, p = .001), and counter-arguing (H4f) (β = .32, t = 9.99, p < .001).

Finally, instrumentality predicted opinion expression offline (H5a) (β = .36, t = 13.65, p < .001) and online (H5b) (β = .26, t = 9.26, p < .001) and counter-arguing predicted opinion expression offline (H5c) (β = .24, t = 8.47, p < .001) and online (H5d) (β = .14, t = 4.80, p = .001) (Figure 3 and Table 2). After controlling demographics, they did not have significant influence except for gender on instrumentality predicting opinion expression online (β = .16, t = 2.95, p = .003) and age on counter-arguing predicting opinion expression online too (β = .07, t = 2.82, p = .005).

Discussion

This study employs CMM to predict individuals’ expressions of opinions offline and online, using the SOS theory. The results confirmed almost all hypotheses. FSI and opinion congruence predicted media surveillance, which predicted elaboration, attention, and discussion. Elaboration predicted structural and procedural knowledge while attention and discussion predicted perceived familiarity. Also, structural knowledge predicted counter-arguing and perceived familiarity predicted information instrumentality. Procedural knowledge was a moderate predictor of information instrumentality and counter-argument. Finally, even after controlling, information instrumentality and counter-arguing predicted the majority of cases of opinion expression in offline and online contexts.

The following section provides explanations for the results and discusses the results in relation to social implications and a future research agenda. It concludes with the study’s limitations.

Explanations for the Findings

In both samples, FSI and opinion congruence predicted surveillance. Individuals who were afraid of other people’s sanctions were motivated to seek information. This is consistent with Hayes et al. (2013) who found that FSI stimulated people to seek out information in order to assess “what the public thinks” (p. 404). Opinion congruency was a predictor too but a positive predictor of surveillance of the dual-nationality issue and a negative predictor of surveillance of the women’s freedoms issue. The outcome on opinion congruency and surveillance of the dual-nationality issue is predicted. However, the results showed that individuals who perceived their opinion to be congruent with that of the majority on women’s freedoms also wanted to know further information about this issue. This can be attributed to the speed of social changes in a society (Noelle-Neumann, 1977). Noelle-Neumann (1977) argues, “In societies and in periods where social change is slow, no strenuous observation of the social environment is necessary to avoid isolation: the norms, expected and approved patterns of behavior, are known as well as the dominant opinions” (p. 145). The Kuwaiti culture is characterized by being collectivist and conservative where people are less likely to accept new ideas and change (Al-Sumait et al., 2021). And since women’s freedom is a culturally and religiously oriented issue, individuals can easily be familiar with what the public thinks regarding this issue without constant or meticulous observation. However, since dual-nationality is a politically oriented issue, it is subject to political negotiations and public opinion shifts.

Attention and interpersonal discussion were the strongest predictors of perceived familiarity according to the t-test value. Attention and interpersonal discussion also predicted procedural knowledge and structural knowledge, but with lower t-test values than that of perceived familiarity. On the other hand, elaboration was the strongest predictor of structural knowledge according to the t-test statistical values. Procedural knowledge and perceived familiarity were predicted thereafter by elaboration according to the statistics. These results shed light on cognitive elaboration, as a form of personal elaboration and interpersonal discussions as a form of collective elaboration (Ho et al., 2013). Paying attention and interpersonal discussions add to people’s perceived familiarity more than their structural and procedural knowledge. Paying attention to media messages and getting involved in interpersonal discussions are subject to personal selectivity and preferences. Individuals selectively pay attention to what they want to hear from media, and this can enhance their perceived familiarity. They selectively associate with like-minded people who have interests similar to their own. Thus, individuals obtain information that reinforces and extends the knowledge that they already have. In contrast, elaboration, as a personal form of elaboration, provides individuals with more cognitive complexity. It seems that people who are left alone to think quietly can produce links between different issues to enhance their structural knowledge and awareness of practical ways to solve problems.

Interestingly, the statistical strength of perceived familiarity predicting information instrumentality was higher than that of structural knowledge. The prediction of perceived familiarity for information instrumentality is self-explanatory. People who know a lot about an issue will perceive that their information will be conducive to opinion expression. As for the prediction of structural knowledge for counter-arguing, people who connect an issue with other issues develop a comparative and analytical knowledge that enables them to see strengths and weaknesses in an argument. Those people will have cognitive complexity and cognitive maps (Eveland & Schmitt, 2015) that make them generate counterarguments that they can use for opinion expression (Polk et al., 2009).

Except for a few cases, the order of predictions reflecting statistical strength of relationships was very similar for both samples (Table 2). The exceptions were when surveillance predicted elaboration first, then attention, and last interpersonal discussions for the dual-nationality sample and surveillance predicted attention first, then discussion, and finally elaboration for the women’s freedoms sample. The second exception was that procedural knowledge predicted instrumentality first then counter-arguing for dual-nationality while it predicted counter-arguing first and information instrumentality second for women’s freedoms. Apart from these 5 different orders in ranking, the other 20 direct effects all had the same ranking for both samples. These results confirm the model’s validity.

Additional outcomes also confirm the model’s validity. For example, instrumentality was a stronger predictor of opinion expression than counter-arguing in both opinion expression contexts, offline and online. In addition to this model validation, it is interesting to see that instrumentality is a stronger predictor of offline and online opinion expressions than counter-arguing. Individuals expressed their opinions by communicating information they know about an issue more than they counter-argued the opposite opinion. This could be attributed to three factors. First, counter-arguing entails analytic and complex cognitive effort. For people to counter-argue, they need to identify inconsistency within an argument to invalidate it. This demanding style of thinking cannot be embraced often by people. Second, since counter-arguing depends on finding discrepancies within an argument, it entails an awareness of different perspectives on an issue. In general, people tend to receive information for cognitive consistency and reinforcement, and few people would view heterogeneous perspectives on issues. Third, counter-arguing involves exposing contradictions of other people’s arguments and opinions while expressing opinions. This method may be considered harsh in many social and cultural contexts.

As for why instrumentality and counter-arguing predicted opinion expressions more strongly in offline contexts than online contexts for both samples, it seems that people in offline settings are obliged to confirm their personal presence and thus they need to express their opinions. Also, they have to abide by the etiquette of offline contexts and provide inputs in conversations. In contrast with this, the freedom people have online means they feel little pressure to evaluate their information instrumentality and counter-arguing abilities. Online, it seems other cognitive decision aspects are more important when deciding to speak out.

Implications of the Studies

The findings of this study can provide important practical implications and contributions to understanding the factors influencing opinion expression in a sociopolitical context. By integrating CMM and SOS, this study implies that individuals’ ways of cognitive internalization of information enables them to overcome FSI and become active participants in discussions about moral-laden and controversial issues. This implication can be important to policymakers in democracies who need to understand that uncensored, objective, and unbiased information can prepare individuals to become more active in discussing political matters.

Nationally, programs that foster open dialogue and tolerance for unrestricted information within society can reduce the prevalence of uniformity of ideas and concepts as well as pressures to conform. Such programs can be designed to include diversity of opinions and teach acceptance. These programs can encourage individuals and promote engagement among individuals who might otherwise remain silent due to perceived social sanctions. Such programs can be especially important if they start with people at a young age, including youths in schools and university. These programs can also be particularly useful in less democratic countries that are new to democratic rule. It seems that a combination of information affordability along with an atmosphere that encourages opinion diversity and opinion expression can be a great recipe for healthy political systems.

Recommendation for Future Studies

This study is one of the few that test CMM in an online environment. As information viewed online can be chosen by the individual, reflecting an echo-chamber effect, future studies need to look at how such an information atmosphere influences information consumption and learning. A media reinforcement motivation is probably important for the way people join or follow specific online groups presenting and circulating specific information. This may limit or expand learning from online media.

This study tested the concept of information instrumentality in relation to opinion expression. We suggest that this concept be examined in a more general way that can warrant its adoption in different behaviors, settings, and issues. For example, the survey items of this concept can be tailored to reflect confidence in retained information and knowledge in enabling individuals to vote better, make decisions about political and social engagement, and other matters. We believe that such a component about decisions relating to information can be very important in CMM and important in relation to the decisions individuals make in life.

To better reflect this model of CMM and SOS, a future study that is comparative in nature could provide more fruitful results. Testing the model in democratic and non-democratic societies across various political issues could show a more workable and adaptable model that can be developed for different political settings. Such a study would reflect the nature of received information, and of censorship, on the way people learn information and use it for expression.

Limitations of the Study

This study has some limitations that need to be considered. First, like other CMM studies, it is a cross-sectional study that indicates causality at one point in a time. Future studies need to adopt a longitudinal approach due to the fact that learning about an issue from mass media takes time to occur. Also, since this study depended on a survey responses, an experimental design could be an alternative research design in a controlled research setting. Second, this study controlled only for gender and age. The survey did not include other important demographic variables such as income and education. Furthermore, this study was conducted in Kuwait, a country that is collectivist in nature. The results may be limited in culturally individualist settings. Also, the study examined the issues of dual-nationality and women’s freedoms. For generalizability purposes, other issues need to be tested using national samples. Finally, the first sample in the study predominantly included young people aged between 18 and 25 and the second sample had more females than males. Even though the performed SEM controlled for gender and age, a generalization of the study’s results need to be carefully approached.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)