Background

There were about 16 million women between 15 to 19 years old give birth each year, about 11% of all births (WHO, 2011). About 16 million women between 15 to 19 years old give birth each year, about 11% of all births (WHO, 2011). Children of adolescent mothers had lower cognitive and language abilities than children of adult mothers. Compared to adult mothers, adolescent mothers demonstrated lower levels of positive parenting behaviors and higher levels of negative regard during interactions with their children (Rafferty et al., 2011).

Adolescent mothers are still developing physiologically and psychologically and the maternal role may conflict with their own developmental trajectory. Adolescent mothers are likely to seek prenatal care later than adult mothers and make poorer nutritional choices, putting them at high risk of having a preterm baby (Ryan et al., 2011). There are many maternal and infant factors that may contribute to the adolescent mother’s difficulty in adapting to the maternal role.

Adolescent Motherhood Development

The normal cognitive and psychological development of an adolescent plays an important part in adapting to the maternal role, influencing both the mother’s integration into the role and the infant’s development (Furstenberg et al., 1987; Patel et al., 2012). However, motherhood has been considered as a developmental task of adulthood because of the intrapersonal transition period. Motherhood occurs when changing from non-parent to parent, and adolescent mothers may not be able to intuitively make this transition (Mercer et al., 1986). Rubin originally described the maternal role as a complex cognitive and social process that is learned, reciprocal, and interactive. Maternal role is the product of culture and development and refer to acts a mother is expected to perform in relation to her child (Rubin, 1967). Moreover, the egocentric nature of an adolescent may conflict with the development tasks of motherhood (Black et al., 2012). The egocentricity of an adolescent may also adversely affect her ability to parent, because many mothering tasks draw on an adult woman’s level of social and cognitive abilities to respond, guide, and make choices for her child in appropriate ways. Interactions between adolescent mothers and their infants have been found to be intrusive, insensitive, or inappropriate with little reciprocal interaction between the mother and infant (Mayers, Hager-Gundy, & Buckner, 2008). They have also been found to talk less, be less expressive, show less enjoyment, and be more controlling than adult mothers (Culp, Applebaum, Osofsky, & Levy, 1988), when interacting with their infants.

Infant feeding is one of the significant tasks of parenting where mothers interact with their infants. Interactions between mothers and infants can be seen during early mother-infant feeding interactions. Adolescent mothers are at a higher risk to be less sensitive and responsive in the early months (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2000). Researchers have found that an adolescent mother who lacks knowledge about normal child behavior has unrealistic expectations and misinterprets her child’s behavior (Dallas et al., 2000). These expectations may lead to the adolescent mother raising a difficult child because she was unprepared for the responsibility (Dallas et al., 2000). However, Rentschler (2003) found that motherhood may be a positive experience for some adolescent mothers. Having a baby improved their lives, and the experiences of being a mother helped them to feel more mature, self-reliant, and self-confident (Spear, 2004). During feeding, mother and infant begin to learn about each other and build up their relationship (Neu & Robinson, 2008). Therefore, infant characteristics are also a significant aspect of interaction and building the relationship.

Preterm Infant

An infant born preterm (babies born before 37 weeks gestation) may present a significant challenge to the transition to parenting for an adolescent mother and this transition may be overwhelming when compared with adult mothers. Infants born preterm have shown a more limited range of interactional skills and lower quality interaction with their mother compared with full-term infants (Barnard et al., 1984; Korja et al., 2008). During early infancy, many preterm infants provide unclear distress signals, and in general, they are less alert, active, and responsive and more easily stressed and over stimulated than low risk full-term infants (Eckerman et al., 1995; Muller-Nix et al., 2004). Being born premature puts the infant at risk for maladaptive feeding behaviors as well as being maladaptive in the social and emotional aspects of the feeding interaction (Schmid et al., 2011).

Adaptiveness Feeding Behavior

For a mother, adaptive feeding behavior refers to her ability to be sensitive, responsive, nurturing, comforting, and protective of her infant and supportive of the infant’s participation in feeding (Fonagy, 1998; Pridham et al., 1999). Adaptiveness may be a result of organized care from a mother’s perspective. The implicit goal of adaptive maternal behavior is to support the infant’s nutritional intake, development, growth, physical health, and develop a significant relationship. Moreover, the adaptiveness of the infant may reflect the conditions that the infant brings to the activity. These include biological conditions such as maturity at birth, health conditions, and temperamental characteristics (Pridham et al., 1999). For a preterm infant, adaptive feeding behavior refers to organization for and participation in feeding, expressed in such behaviors as orienting, alerting, and signaling to reduce or increase stimulation (Sroufe, 1995). It is related to the infant’s abilities and preference to interact with the mother (Schore, 2000).

Researchers have shown links between maternal feeding behaviors and infant feeding behaviors (Brown & Pridham, 2007); in particular, the adolescent mother’s potential to accept the change and responsibility of being a mother may also influence the quality of maternal and infant feeding behaviors (Benson, 1996; Hannon et al., 2000). As a result, adolescent mothers were less sensitive to their infant (Percy & McIntyre, 2001), provided less verbal stimulation, responded less often in a way that is contingent to the needs of their infant, and were more negative (McDonald Culp et al., 1996). In the present study, the purpose was to examine the adaptiveness of early maternal feeding behavior and adaptiveness of infant feeding behavior between adolescent mothers and adult mothers at three time periods (discharge, 1 and 4 months corrected age [CA]). Corrected age is the infant’s chronological age minus the number of weeks the infant was born before 40 weeks gestation (Engle et al., 2004).

The hypotheses were as follows:

-

Adolescent mothers will score lower than adult mothers on the Positive Affective Involvement and Sensitivity/Responsiveness (PAISR) scale and Regulation of Affect and Behavior (RAB) scale at each data collection point (discharge, 1, and 4 months corrected age).

-

Infants of adolescent mothers will score lower than adult mothers on the Infant Positive Affect, Communication, and Social Skills (IPACS) scale and the Infant Regulation of Affect and Behavior (IRAB) scale at each data collection point (discharge, 1, & 4 m onths corrected age).

-

Adolescent mothers will score lower than adult mothers on factors associated (comfort and experience with physical contact) with adaptiveness at each data collection point (discharge, 1, and 4 months corrected age).

Methods

This descriptive study was a secondary analysis of data from a longitudinal study conducted by Brown & Pridham (2007) to assess the adaptiveness of the mother’s early feeding behavior on the infant’s later feeding behavior. This study identified adaptiveness using videotape to record mother and infant behaviors in periods of feeding and also compares feeding behaviors and adaptivenees between bottle-feeding and breastfeeding. The institutional review board approved both the original and the current study. The total of 37 samples was collected in the previous study.

For this study an adolescent was defined as a woman 19 years of age or less, a young adult between 20-24 years old, and an adult as > 25 years old. Researchers have shown behavioral similarities between adolescent and young adult mothers (Kingston, Heaman, Fell, & Chalmers, 2012). Therefore, this study only examined data from the adolescent and adult mothers. The sample consisted of 12 mother-infant dyads. All six adolescent mothers and their infants from Brown & Pridham (2007) were included in the study and six adult mothers and their infants were randomly chosen. The inclusion criteria for the mother were 17- 19 years old for the adolescent mother group and 25 years or older for the adult mother group. They were all able to speak and read English. Inclusion criteria for the infants were 35 weeks gestation or less. The infants were an appropriate weight for their gestational age. There were no major congenital abnormalities and no known drug exposure. The sample included both breastfeeding and bottle feeding infants.

Measure

Adaptiveness of maternal and infant feeding behaviors was measured from video recordings and coding by research assistants at a school of nursing in the US, using the Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA). The PCERA includes a 65-item observational rating scale that was designed to assess the mother and the infant’s feeding behaviors. It contains six scales: two maternal, two infant, and two dyadic. This study only uses the maternal and infant scales. Each item was rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 indicating behavior that is adaptive in quality, and 1 indicating behavior that is maladaptive (Clark, 1999).

The first of the two maternal scales measured the mother’s interactive behaviors and was labeled Positive Affective Involvement and Sensitivity/Responsiveness (PAISR). There were 16 items in this scale. The items included sensitivity and responsiveness to the infant’s cues, warmth and kindness of voice tone, expression of positive affect and enjoyment, competence in structures and mediation of the environment to support nutrient intake and a positive feeding experiences, visual regard, and mirroring of infant’s feeling. The second scale was Regulation of Affect and Behavior (RAB). Items included in this scale describe how competently a mother structures a feeding, mediates the infant’s feeding environment, and provides a positive and well-regulated social-emotional experience for her infant. Items in the RAB scale also describe a mother’s sensitivity and responsiveness to her infant and her curtailment of such behaviors as talking with an angry tone of voice, expressing a negative attitude toward the baby, behaving intrusively, handling the infant roughly or abruptly, and responding inflexibly.

The first of the two infant scales was Infant Positive Affect, Communication, and Social Skills (IPACS) and included 12 items to rate the quality of attention, motoric and communicative skills, social initiative, and responsiveness. The second scale, Infant Regulation of Affect and Behavior (IRAB), includes 11 items for describing the infant’s expression of negative effect, fearfulness or tension, irritability, soberness, avoiding or averting behavior, attention to feeding, and interest in the environment (Brown & Pridham, 2007; Clark, 1999).

The composite variables demonstrated high levels of internal consistency, measured by the Cronbach alpha, ranging from 0.93-0.97 for the two maternal scales and 0.85-0.89 for the two infant scales (Brown & Pridham, 2007). In addition, the PCERA has been used with preterm infants (Pridham, Lin, & Brown, 2001) and discriminate validity between high-risk and well-functioning mothers has been demonstrated (Clark, Paulson, & Conlin, 1993). Inter-rater reliability ranged from 79% to 84% agreement across codes, with a mean of 81% agreement.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to examine the distribution of maternal and infant feeding behaviors. The demographic characteristics of mother and infant were described using frequency and percentage. The data were described as mean and standard deviation. The comparison between adolescent and adult mothers used a non-parametric statistical test, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as there was a limited sample size. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP version 9 software. Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

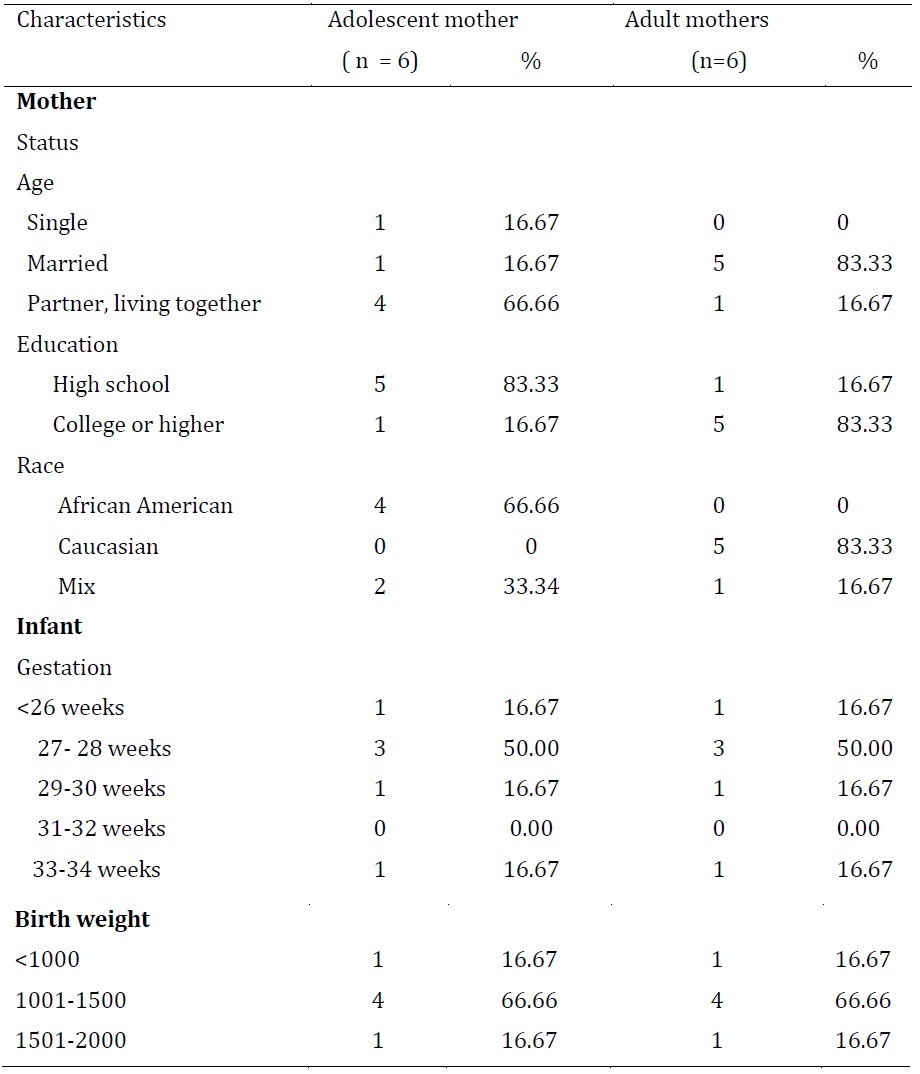

Data for 12 mother-infant dyads were analyzed. Most of the adolescent mothers were living with their partner (66.6%), while most of the adult mothers were married (83.33%). On average the adult mothers had more years of schooling (12.66 years for adolescent mothers versus 15.33 years for adult mothers). The adult mothers had at least a high school diploma. Most adolescent mothers were African-American (66.6%) while most of the adult mothers were Caucasian (83.3%). Infants were matched for birth weight and gestational age for the two groups. Sixty-seven percent of the infants weighed 1001-1500 grams and 50% were born at 27-28 weeks gestation as shown in Table 1.

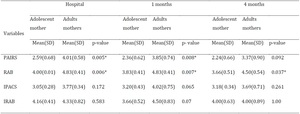

The adolescent mothers had significantly lower scores of adaptiveness of maternal feeding behaviors than adult mothers. Adolescent mothers’ PAISR scores were significantly lower than the adult mothers’ scores just before hospital discharge (p=0.005) and at 1 month corrected age (p =0.008). However, there was no significant difference in PAISR scores at 4 months corrected age between adolescent and adult mothers (p =0.092). Adolescent mothers’ RAB scores were significantly lower than adult mothers’ scores at all three time periods; just before hospital discharge (p=0.006), 1 month corrected age (p=0.007) and at 4 months corrected (p=0.037).

There were no significant differences in IPACS at just before hospital discharge, 1 month corrected age, or 4 months corrected age when comparing infants of adolescent mothers and infants of adult mothers. There were also no significant differences in IRAB at just before hospital discharge, 1 month corrected age, or 4 months corrected age when comparing infants of adolescent mothers and infants of adult mothers as shown in Table 2.

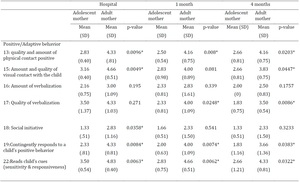

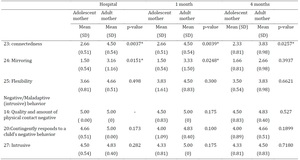

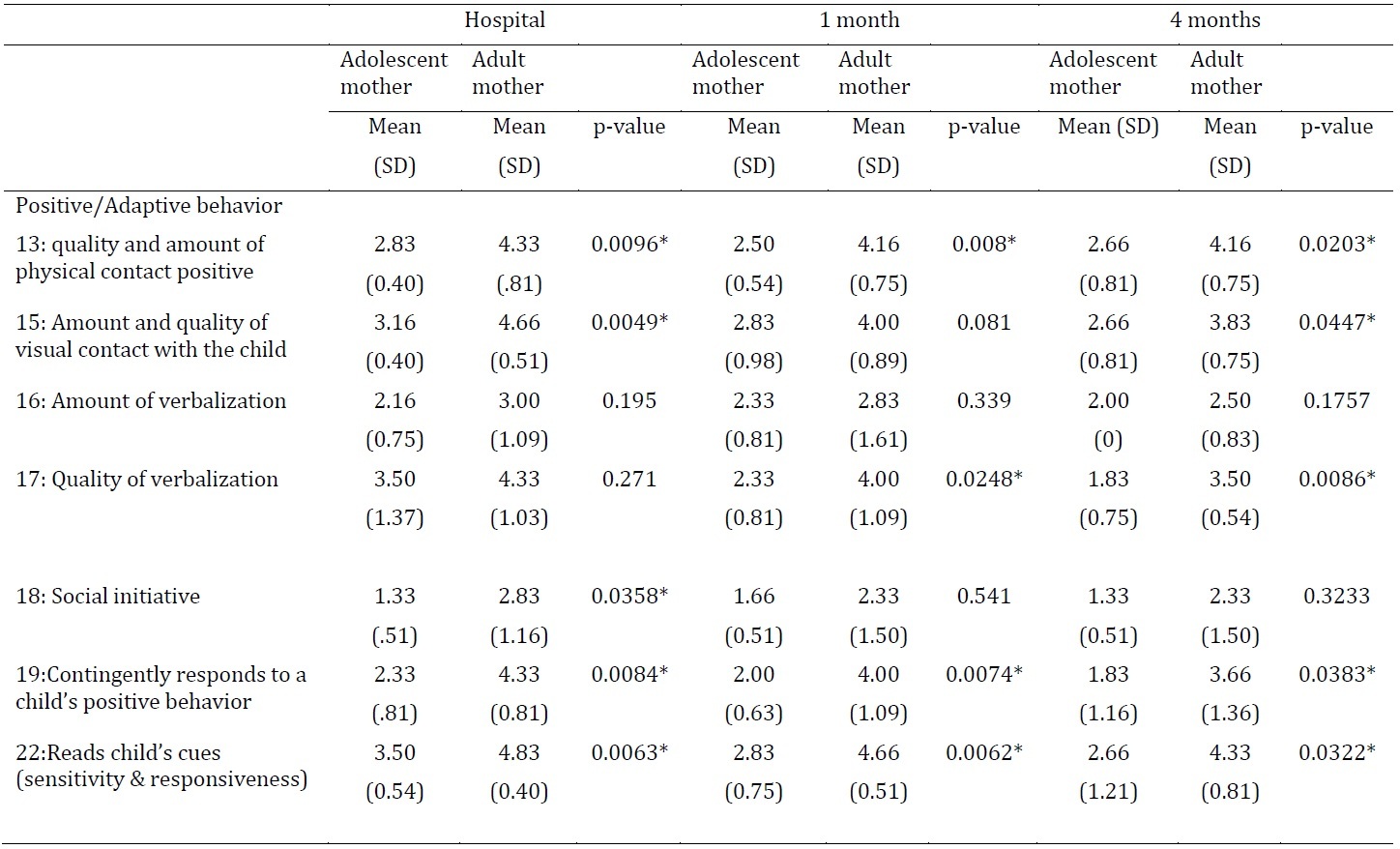

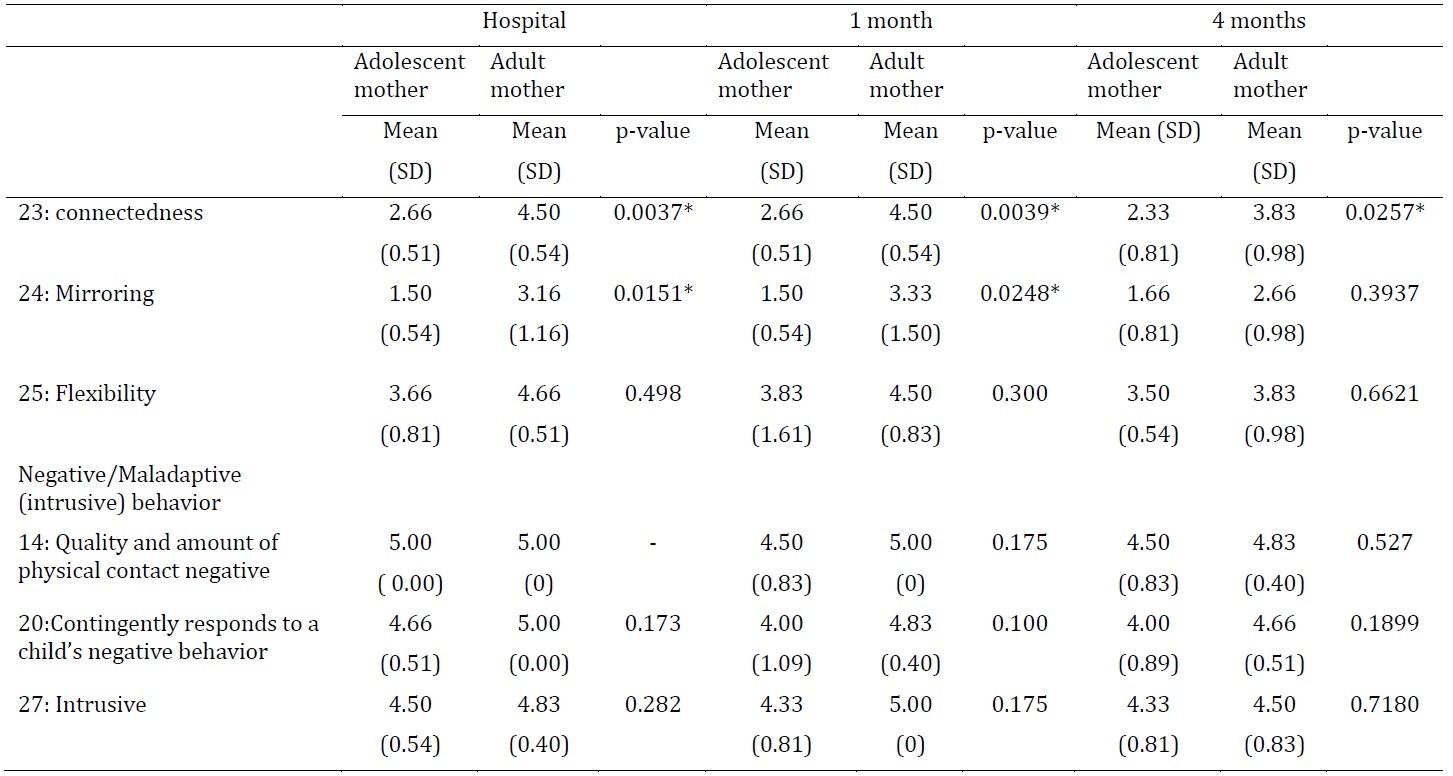

When the factors that are associated with adaptiveness were compared between adolescent and adult mothers, there were some positive (adaptive) and negative (maladaptive/intrusive) factors that were significantly different between the two groups. The quality and amount of positive physical contact for adolescent mothers was significantly less than in adult mothers just before hospital discharge (p=0.009) and at 4 months corrected age (p=0.023). Adolescent mothers looked at their infants significantly less often and had significantly less visual regard for their infants (amount and quality of visual contact with the child) than adult mothers just before hospital discharge (p= 0.004) and 4 months corrected age (p=0.044). The quality of the adolescent mothers verbalizations were significantly less meaningful and developmentally appropriate when compared to the adult mother at 1 month corrected age (p= 0.024) and 4 months corrected age (p=0.008). Adolescent mothers initiated social interactions significantly less often than the adult mother just before hospital discharge (p=0.035). The adolescent mother contingently responded to their child’s positive behavior significantly less often than adult mothers at all three time points; just before hospital discharge (p=0.008), 1 month corrected age (p=0.007), and 4 months corrected age (p=0.038). Adolescent mothers read their child’s cues significantly less often than adult mothers at all three time periods; just before hospital discharge (p=0.006), 1 month corrected age (p=0.006), and 4 months corrected age (p=0.032). Adolescent mothers were significantly less connected to their infant than adolescent mothers at all three time periods; just before hospital discharge (p=0.003), 1 month (p=0.003), and 4 months corrected age (p=0.025). Adolescent mothers were also able to mirror the child’s affect and/or behavior significantly less often than adult mothers just before hospital discharge (p=0.015) and at 1-month corrected age (p=0.024) as shown in Table 3.

There was no significant difference in quality and amount of verbalizations, negative physical contact, contingently responding to the child’s negative behavior, flexibility, and intrusive behavior at any time point for adolescent or adult mothers as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The study aim was to compare the adaptiveness of early maternal feeding behavior to adaptiveness of infant feeding behavior between adolescent and adult mothers. The adolescent mothers had significantly less positive affective involvement, sensitivity, and responsiveness than adult mothers just before hospital discharge and at 1 month corrected age. However, the adaptiveness of maternal feeding behavior between adolescent mothers and adult mothers were not significantly different at 4 months corrected age. Thru feeding, the mothers learn to communicate with their infants, and respond to their infant’s agenda, and interpret their feeding behavior. The lack of significant findings at four months may indicate the adolescent mother has come to know her infant, particularly her infant’s feeding skills. Future studies could examine the development of the adolescent mother’s feeding behaviors. Adolescent mothers had significant less regulation of affect and behavior than adult mothers at all three time periods; just before hospital discharge and at 1 and 4 months corrected age.

Typically, adolescent mothers have less healthy relationship skills related to their infant than adult mothers (Andreozzi et al., 2002). Maternal sensitivity is challenging for many adolescent mothers because of their developmental stage (Flaherty & Sadler, 2010). The findings of this study were consistent with previous researchers who reported that adolescent mothers were significantly less sensitive to their infant than adult mothers (Percy & McIntyre, 2001).

The mother-infant relationship depends on the infant’s ability to give clear communication cues and the mother’s ability to read respond quickly and sensitively to her infant (Ainsworth et al., 1978). Maternal responsiveness includes appropriate maternal behaviors that are prompt in the situation, identifiable, and direct antecedents to the behavior of the infant (Bornstein & Tamis-Lemonda, 1997; Lewis, 1999). Another attribute of maternal responsiveness is the mother’s ability to recognize her infant’s cues consistently and to act on those cues. Adolescent mothers were found to be significantly less contingent to the needs of their infant’s positive behavior than adult mothers. However, no difference was found between adolescent mothers and adult mothers in the ability to respond contingently to their infant’s negative behavior. This is contrary to Ruff (1990) who found that adolescent mothers showed a decrease in their response to distress in their infants.

Quality and amount of positive physical contact was significantly less in adolescent mother than adult mothers. There were no previous studies comparing physical contact between the infants of adolescent and adult mothers. However, the physical contact in the study of Oswalt et al. (2009) found adolescent mothers indicated low levels of comfort and experience with physical contact. Adolescent mothers have also been shown to be less knowledgeable about child development (Mann et al., 2004). The initiation of social contact was also significantly less in adolescent mothers. Although there have been no studies about this aspect of infant behavior with adolescent mothers, in a study of adult mothers, social contact was significantly linked to infant attachment behaviors (Lowinger et al., 1995). Infant feeding behaviors are associated with a secure attachment style of mothers (Wilkinson & Scherl, 2006); thus, adolescent mothers need more support to let them attach with their infant more, starting with physical and social contact.

Quality of verbalization was also significantly less in adolescent mothers. When compared to older mothers, adolescent mothers were characterized as less sensitive to infant cues and less verbal with and responsive toward their infants (Barnard, 1997; Ruff, 1987; von Windeguth & Urbano, 1989). Connectedness and mirroring were significantly less in adolescent mothers; these behaviors in both adolescent and adult mothers may need more evidence to support maternal adaptiveness in infant feeding behaviors. Flexibility and intrusiveness were not significantly different in adolescent and adult mothers; however, we have found no evidence supporting the idea that they relate to infant feeding behaviors.

Study Implications

This part of the feeding interaction could be played back and discussed with the mother as part of a feeding intervention, especially in adolescent mothers. The identification of maternal behaviors that are regulating or dysregulating for a specific infant provides a means of individualizing care. For health care professionals, supporting feeding behaviors in adolescent mothers is needed to encourage them to adapt to their role as a mother in feeding their infant.

Limitations

Despite the small sample size, the results show promise. Across two groups of the same sample size, repeated measurements of PCERA, using non-parametric statistics, significant differences between groups were found. Perhaps with a larger sample size, the adaptiveness of maternal feeding behaviors and infant feeding behaviors may become more apparent.

Conclusion

Maternal sensitivity is the center for many challenges for many adolescent mothers regarding their developmental stage and the multiple stresses in their lives. Adolescent mothers caring for infants may not have achieved the stage of formal operational stage. Maternal feeding behavior as a task of parenting is difficult when the adolescent mothers cannot view that their actions, feeling, and attitudes directly affect their infants. Results showed adolescent mother had significantly less amount and quality of visual contact with the child, quality of verbalization, social initiative, quality and amount of physical contact positive contingently responds to a child’s positive behavior, reading child’s cues, connectedness, and mirroring than adult mothers. Thus, early-preterm infant-feeding adolescent mothers require more help to adapt quality maternal feeding behaviors.

Although the study of early preterm infant feeding in adolescent mothers was conducted in the US, and there is no evidence of preterm infant feeding based on observation tool in Asian counties, we recognized that cultural differences affect individual and collective experiences and behaviors (Leininger & McFarland, 2002). Based on the findings of the study with a limited sample size, it still demonstrated an important point of view as to how feeding in adolescence is more difficult than it is for adult mothers. This study should be considered as a pilot data of a population based survey to establish and identify problems of maternal-infant feeding behaviors in adolescent mothers in Asian countries. The results of a population-based survey should display a scale of feeding behavior problems in adolescent mothers. It will also become a set of necessary information to encourage health care policy to support successful infant feeding in adolescent mothers and help adolescent mothers achieve a level of competence in interaction with their babies

Biographical Notes

Supannee Kanhadilok is a senior lecturer at Boromrajonnani College of Nursing, Phraputthabat, Saraburi, Thailand. Her research trajectory focuses on maternal competence using breastfeeding behaviors especially in group of adolescent mothers. She can be reached at e-mail: supannee@bcnpb.ac.th

Lisa Brown is an assistant professor at the School of Nursing, Virginia Commonwealth University, USA. Her program of research focuses on maternal competence by assessing mother-premature infant feeding interactions and designing interventions to support competence. She has developed a method of assessing mothers’ sensitivity and responsiveness to their infants’ feeding.