Introduction

A number of people often believe that corporations’ misbehavior, including malfeasance and embezzlement, causes serious social problems and results in anti-corporate sentiment among citizens. However, corporations’ sincere commitment to community values can enhance trust in a democratic society and furthermore provide positive financial outcomes for corporations. In other words, corporations’ active engagement in community, as citizens in civil society, means that all corporations should also serve the community by maintaining ethical and legal standards. This allows corporations to gain public approval of their existence in the society by operating in a socially responsible manner, such as through community outreach or philanthropic programs.

Notably, the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has emerged as a prominent term in scholarship on the social role of business. Social responsibility is “a value that specifies that every situation – from family to firm is responsible for its members’ conduct and can be held accountable for its actions” (Boynton, 2002, p. 243). Applied to the corporate setting, CSR suggests that corporations should address social issues, such as improving the welfare of society, protecting the environment, overcoming poverty, and enhancing employees’ well-being. A growing body of research in organization-public relationships is exploring how CSR activities can affect the relationship between a profit company and its public, such as consumers. For example, CSR activities are more likely to make a positive impact on sales, employee attitudes, management support, media coverage, and working relationships with stakeholders (Yankey, 1996).

Yet CSR-related research has paid little attention to the social relations involved in practicing CSR. It has also barely attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of CSR practices in terms of the relationship between an organization and its publics (Kim & Choi, 2013). By focusing on the importance of the relationship, this study aims to investigate whether individuals’ perceptions of CSR activities affect their attitudes toward for-profit companies and intent to purchase products in a South Korean context. Specifically, the study further explores the effects of individuals’ perceptions of communal and exchange relationships with companies. Examining these two types of relationships adds an important theoretical dimension of CSR to not only sustain a civil society and build community, but also enhance organizational effectiveness. Moreover, additional theoretical implications are offered by understanding how business outcomes can result from the perceptions of communal and exchange relationships between companies and their publics.

Theoretical Frameworks: Communal and Exchange Relationships as OPR

As one of the societal actors, corporations also need to consider certain relationships with other publics, including consumers, employees, governments, community residents, and media. In other words, corporations build and nurture relationships with other societal actors to enhance organizational effectiveness. Corporations manage an organization-public relationship (OPR) in which the actions of either entity impact the economic, social, political, and/or cultural well-being of the other entity (Ledingham et al., 1997). The patterns of interaction, transaction, and exchange between corporations and their publics occur through such relationships.

Although a relationship is an abstract and elusive construct (Ki & Hon, 2012), OPR researchers have attempted to conceptualize and develop its dimensions, which are considered the perceived quality of an OPR. By identifying its critical dimensions, corporations can use measurable indicators that effectively show the evaluation of CSR programs. While relationship dimensions have been identified by OPR researchers (e.g., Grunig et al., 1992; Hon & Grunig, 1999; Ledingham & Bruning, 1998), some of the most selected key dimensions include six measures proposed by Hon & Grunig (1999): control mutuality, satisfaction, trust, commitment, communal relationship, and exchange relationship.

Control mutuality refers to “the degree to which parties agree on who has the rightful power to influence one another” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 3). When a corporation needs to make a certain decision regarding its consumers, the opinion of each party may be reflected. Control mutuality assesses which party has more power over the other to decide relational goals. While control mutuality covers a cognitive dimension, the second measure of relationship quality, satisfaction, is more concerned with affection and emotion (Grunig & Huang, 2000). Satisfaction is defined as “the extent to which each party feels favorably toward the other because positive expectations about the relationship are reinforced. A satisfying relationship is one in which the benefits outweigh the costs” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 3). It is critical that a corporation should be able to identify and satisfy publics’ needs. The third dimension includes trust, which refers to “One party’s level of confidence in and willingness to open oneself to the other party” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 3), while consisting of three variables: integrity, dependability, and competence. A public’s trust in a corporation relies on the extent to which the corporation keeps its word (Ledingham & Bruning, 1998). The fourth dimension of OPR is commitment. This indicator is defined as “the extent to which one party believes and feels that the relationship is worth spending energy to maintain and promote” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 3). Commitment is multidimensional and is comprised of affective, continuance, and normative attributes.

This study pays more attention to communal relationship and exchange relationship to evaluate CSR practices. Hon & Grunig (1999) conceptualized communal and exchange relationship as follows:

In a communal relationship, both parties provide benefits to the other because they are concerned for the welfare of the other — even when they get nothing in return. For most public relations activities, developing communal relationships with key constituencies is much more important to achieve than would be developing exchange relationships. (p. 3)

In an exchange relationship, one party gives benefits to the other only because the other has provided benefits in the past or is expected to do so in the future. In an exchange relationship, a party is willing to give benefits to the other because it expects to receive benefits of comparable value to the other. In essence, a party that receives benefits incurs an obligation or debt to return the favor. Exchange is the essence of marketing relationships between organizations and customers and is the central concept of marketing theory. However, an exchange relationship often is not enough. The public expect organizations to do things for the community for which organizations get little or nothing in return. (pp. 20-21)

These days, such publics as customers and community residents often expect corporations to do things for community for which corporations get little or nothing in return through a variety of CSR practices. This suggests that communal relationship between a corporation and its publics is particularly ‘‘important if organizations are to be socially responsible and to add value to society as well as to client organizations’’ (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 21). When value and common good are created and shared in a community, its members will be more likely to experience the importance of collaborative value.

The Importance of Communal Relationships between Corporations and Community OPR researchers and practitioners have been interested in how CSR practices can best serve organizations and the community. In particular, researchers have examined whether CSR practices, such as corporate giving, could contribute to organizational development (Bae & Cameron, 2006; Hall, 2006). CSR activities make a contribution to the development of a democratic society and community. They also play a socially responsible role for the well-being of employees and the community (Molleda & Ferguson, 2004). This viewpoint implies that corporations should highlight the creation of business values, as well as making profits.

CSR practices may enhance a philosophy of collaboration and lead to positive cooperative behaviors among community members (Jin, 2015). In the process of collaborating with local governments, nonprofits, activist groups, and community members, CSR practices enable for-profit companies to play one of the essential roles of a social bridge by connecting with those societal actors. This means that as society members, corporations also should bear responsibility and participate in problem solving. For example, when the entire community faces an environmental problem, all the societal actors need to resolve it through collective action and cooperation.

Importantly, communal relationships can become the core value of CSR practices through which corporations and their publics communicate with one another in a pluralistic system. OPR researchers argue that communal relationships are more likely to decrease the likelihood of unsupportive behaviors towards organizations, such as unfavorable litigation, regulation, strikes, boycotts, and the like (Grunig, 2000; Hon & Grunig, 1999). However, exchange relationships never lead to the same levels of trust, control mutuality, satisfaction, and commitment as communal relationships do (Hon & Grunig, 1999). Whereas communal relationships are always concerned for the publics’ social welfare, exchange relationships are not. This indicates that stronger communal relationships will be more likely to lead to supportive situations, such as forming positive attitudes among its key public toward a corporation.

In this study, considerable attention is paid to the communal relationship because it helps researchers and practitioners evaluate the effectiveness of CSR practices from the OPR perspective. By looking at the communal relationship between a for-profit company and its key public (i.e., community residents), one will be able to know what positive outcomes can emerge from the communal relationships through CSR activities. For example, if the outcomes include key public positive attitudes and supportive behaviors toward an energy company, then they will be able to enhance the capacity of the company. Moreover, by comparing this with exchange relationships between the company and its public, the study also examines the impact of communal relationships on business effectiveness. By doing so, it can discover whether a communal relationship generates a stronger capacity for organizational development than an exchange relationship. Therefore, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ: To what extent does a communal relationship positively affect a key public’s attitudes and supportive behaviors toward an energy company, compared to the exchange relationship?

Method

Data collection

The data for this study was collected using a web-survey, which is quite convenient given that 97% of South Korean households have Internet access and 65% of citizens aged 16 to 74 use the Internet at least once a day (SK and ES, 2012). On behalf of one South Korean national web-survey company, proportional quota sampling was utilized to recruit 726 respondents residing in Incheon metropolitan city, with eight quotas based on residential location. The respondents were asked to report their opinion about one large energy corporation located in the city that they reside in.

The survey questionnaire includes questions regarding demographics (sex, age, level of education, occupation, time lived at their residence, and residential location), the level of awareness of the energy corporation, and the following major variables.

Survey Instrumentation

The survey questionnaire measured the following key variables on a seven-point Likert scale, except for questions eliciting demographic information.

Communal relationships. Communal relationships between the energy company and Incheon city residents were measured with a valid item developed by using Hon & Grunig (1999) relationship indices. It included two items using a 1- (very strongly disagree) to 7- (very strongly agree) point Likert scale: “The energy company is very concerned about the welfare of people like me” and “The energy company listens to carefully what our community residents say” (α = .854, M = 4.067, SD = .986).

Exchange relationships. Exchange relationships between the energy company and Incheon city residents were also assessed by adopting items from Hon & Grunig (1999) indices. It included three items, using a 1- (very strongly disagree) to 7- (very strongly agree) point Likert scale: “Whenever this company provides a corporate social responsibility activity to the citizens, it generally expects something in return”; “This company takes care of people who are likely to reward the company”; and “This company will compromise with people like me when it knows that it will gain something” (α = .828, M = 4.309, SD = 1.083).

Attitudes. Reflecting that residents are an important public part of an organization, this study developed four statements that were measured on a seven-point Likert scale. Items state: “This company is honest/young/enterprising/respected” (α = .861, M = 4.616, SD = .836)

Supportive behavioral intent. Scholars have often used behavioral intentions rather than measures of an individual’s actual behavior, given that intentions are the most immediate antecedent of behavioral change (Ajzen, 1991). Based on prior studies (Bortree, 2007; Ki, 2006; Zeithaml et al., 1996), the questionnaire measured supportive behavioral intent with the three following statements: “I will be more likely to purchase the products of the company next time”; “I will keep purchasing the products of the company in the future”; and “I will be more likely to purchase the products of the company compared to other competitors” (α = .891, M = 4.807, SD = 1.188).

Level of awareness. Awareness of the company was measured with one item using a three-option scale: 1) well aware (28.8%); 2) just heard (35.3%); 3) don’t know (36.0%).

Results

Participants

This study recruited survey participants by including 726 Incheon metropolitan city residents. Respondents were asked to provide their gender, age, occupation, time lived in the city, and residential location, as well as major variables. Among Incheon city residents, the respondents of this study consisted of 50.6% males distributed across the following age ranges: 28.9% in their 20s; 26.2% in their 30s; 22.4% in their 40s; and 22.5% in their 50s or older. Distribution across the following levels of education is as follows: a high school diploma or lower (26.8%) and college students or higher (73.2%). The amount of time respondents have lived in the city is as follows: 22.4% with 9 years or less; 22.0% with 10 to 19 years; 31.3% with 20 to 29 years; and 24.3% with 30 years or more.

The research question involved assessing whether a communal relationship could positively affect a key public’s attitudes and supportive behaviors toward an energy company, compared to an exchange relationship. To explore the effects of exchange and communal relationships on the two dependent variables after eliminating control variables, two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed.

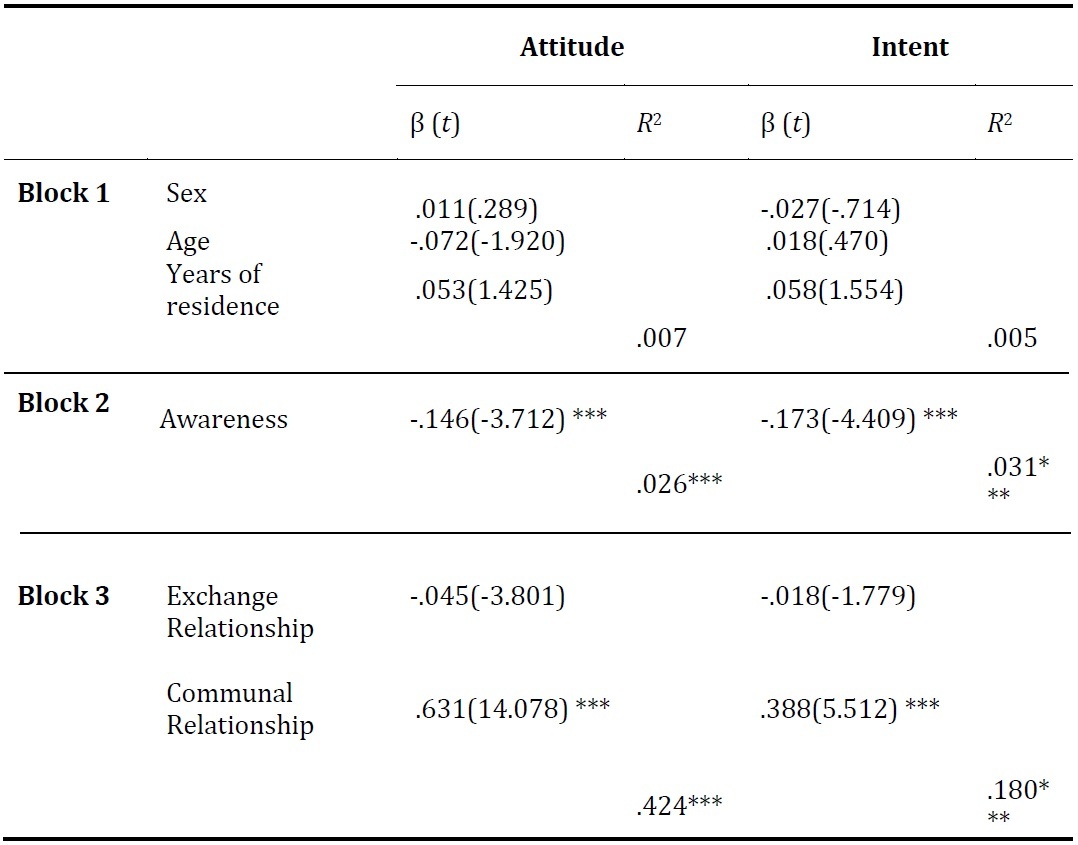

Table 1 demonstrates that the regression model accounted for 42.4% of the total variance in attitude toward the company, reported by its total R2. The first block included the variables of sex (β = .011, p > .773), age (β = -.072, p > .055), and years in residence (β = .53, p > .155), which contributed only 0.7% explanatory power. The second block of variables was awareness (β = -.146, p < .001), which added 1.9% of explanatory power for attitude toward the company. In other words, the more an individual is aware of the company, the more positive attitude they have toward it. The final block addressed the exchange relationship (β = -.045, p > .114) and the communal relationship (β = .631, p < .001) variables, which also significantly increased the R2 change from .026 to .424. Therefore, controlling for awareness and demographics, communal relationships showed their unique effects on attitudes toward the company. Specifically, the more positively individuals perceive communal relationship with the company, the more likely they are to shape good attitudes toward the company. However, an exchange relationship with the company does not tend to shape any attitudes toward the company.

In the second hierarchical regression analysis, the order of variables entered from block one to block four was made congruent with that of the first hierarchical regression analysis. Table 1 shows that the regression model accounted for 18.0% of the total variance in the intent to be supportive toward the company, indicated by its total R2. The first block included sex (β = -.027, p > .475), age (β = .018, p > .639), and years of residence (β = .058, p > .121). These variables contributed only 0.5% explanatory power. The second block of variables was awareness (β = -.173, p < .001), which added 2.6% in explaining the intention to be supportive. In other words, an individual’s awareness tends to play a role in increasing intention. The final block addressed the exchange relationship (β = -.018, p > .603) and the communal relationship (β = .388, p < .001), variables which also significantly increased the R2 change, from .031 to .180. Therefore, controlling for awareness and demographics, communal relationship showed unique effects on the intention to offer supportive behavior toward the company. Specifically, the more positively individuals perceive the communal relationship with the company to be, the more likely they are to be supportive of the company. However, an exchange relationship with the company is not more likely to make people be supportive of the company.

Discussion

This study attempted to investigate how South Korean citizens evaluate CSR practices based on communal and exchange relationships. In particular, it examined whether their evaluations of the two types of relationships are related to their supportive opinions, such as positive attitudes toward corporations and behavioral intentions to purchase products. The findings show that a communal relationship between an energy corporation and its local residents is more related to their supportive opinions than an exchange relationship. That is, a communal relationship tends to generate more positive business outcomes than an exchange relationship. These findings suggest critical implications for the development of corporations and enhancing collaborative values.

Researchers can develop relevant theoretical frameworks for community outreach and CSR programs. CSR practices often aim to engender supportive behavior among employees and community residents. A strong communal relationship can offer several useful benefits to CSR activities. By bridging with other external entities, corporations can create a public dialogue and further a norm of reciprocity and communal relationships. By playing such a role, corporations would realize collaborative values, including alliance, partnership, and solidarity with their local community. If they fulfill their responsibility to be a good citizen, community members will be more likely to perceive the positive aspects of the corporations and do supportive behaviors, such as purchasing their products.

Moreover, this study found that an exchange relationship between a company and the community residents tends to negatively affect their attitude and intention to be supportive toward the company. However, Hon & Grunig (1999) noted that the exchange relationship does equate negatively for organizations and could serve as an antecedent to developing communal relationships. Consumers today expect more than an exchange relationship with suppliers like corporations and expect them to be concerned about the welfare of consumers. Therefore, it would be helpful to identify what factors build exchange relationships and communal relationships between an organization and its public.

For CSR programs, practitioners also should prepare for useful community relations and CSR programs for their local place. They need to focus on building communal relationships with community members through a variety of strategies and tactics. If they can fully satisfy community members and offer a high level of trust by making a solid commitment to the community, they will be more likely to have a strong communal relationship. At the very least, they should not act as if they are only interested in exchange relationships with publics. Perceived exchange relationships between a corporation and its publics can sometimes increase the likelihood of unsupportive behaviors towards it, such as boycotts, unfavorable litigation, strikes, and the like.

Biographical Notes

Soobum Lee, Ph.D. (University of Oklahoma, U.S.), works as a professor in the Department of Mass Communication at Incheon National University, Incheon City, South Korea. His research areas include political communication and public relations.

He can be reached at 119 Academy-ro, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon City, South Korea, 22012 or by e-mail at soolee@incheon.ac.kr.

Bumsub Jin, Ph.D. (University of Florida, U.S.), works as an assistant professor in the School of Advertising and Public Relations at Hongik University, Sejong City, South Korea. His research areas include community-building and public relations, health communication campaigns, and media effects. His works have appeared in such journals as Asian Journal of Communication, Public Relations Review, Communication Quarterly, Journal of Public Relations, and The Korean Journal of Advertising and Public Relations, among others.

He can be reached at 2639 Sejong-ro, Jochiwon-eup, Sejong City, South Korea, 30016 or by email at gabrieljin@hongik.ac.kr.

Correspondence

All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Bumsub Jin at Hongik University, 2639 Sejong-ro, Jochiwon-eup, Sejong, South Korea, 30016 or by email at gabrieljin@hongik.ac.kr.