Background and Literature Review

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) “Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended up to 6 months of age, with continued breastfeeding along with appropriate complementary foods up to two years of age or beyond.” It has been estimated that if nearly everyone breastfed their children, the deaths of 823,000 children under the age of 5 could be prevented every year, along with deaths of 20,000 deaths from breast cancer (Victoria et al., 2016). Therefore, increasing breastfeeding rates should be a public health priority. Fortunately, breastfeeding rates in South Korea have been improving since 2000, but further improvement is still desirable (S.-H. Chung et al., 2013). One first step toward improving breastfeeding rates and duration is understanding attitudes toward breastfeeding and potential barriers to optimal breastfeeding duration.

One potential barrier to successful breastfeeding is the attitude toward breastfeeding in public in a society (Morris et al., 2016; Russell & Ali, 2017). If women are to continue to interact in society while breastfeeding their children according to the WHO guidelines, they will almost certainly need to breastfeed outside the privacy of their homes. While some women may choose to use already established private spaces in public, for example, public bathrooms, or specially designed nursing rooms, doing so can be an unnecessary disruption to social interactions. Therefore, many women need to find a way to feed their children while in public. If a woman feels that breastfeeding in public is acceptable in her culture, she may be more likely to breastfeed and to breastfeed exclusively per the WHO guidelines, but if she feels like she is expected to use a bottle in public, she may be less likely to breastfeed or more likely to stop breastfeeding to use formula exclusively. It is reasonable to assume that public opinion can influence a woman’s decision to breastfeed or to continue breastfeeding.

To test that assumption, we decided to compare public opinion about breastfeeding in public with breastfeeding rates in different countries. We therefore formulated our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Cultures where breastfeeding in public is more acceptable will have higher breastfeeding rates at 6 months and 1 year.

We also wanted to test whether individuals’ opinions about breastfeeding in public would affect their own feeding behaviors. A study of four European countries (Sweden, Scotland, Italy, and Spain) found that women who breastfed in public were less likely to stop breastfeeding in their baby’s first year of life (Scott et al., 2014). A correlation in this case could further support the importance of normalizing public breastfeeding to increase breastfeeding duration.

Hypothesis 2: People with positive attitudes toward breastfeeding in public may breastfeed for longer durations.

If attitudes about breastfeeding affect breastfeeding rates and duration, it logically follows that it would be valuable to understand how people’s experiences were likely to affect their attitudes. A recent study in China found that 65% said it was acceptable to breastfeed in public, and “80% felt that breastfeeding in public was appropriate and decent and did not violate social morality” (Zhao et al., 2017, p. 316). They also found that women, married people, and those with children were more likely to be supportive of breastfeeding in public (Zhao et al., 2017). We hypothesized that the same might be true in Korea. In addition, we expected that those with breastfeeding experience and with experience breastfeeding in public were more likely to have positive attitudes toward breastfeeding in public.

However, it should be noted that people’s attitudes about what is acceptable for other people and what is acceptable for their own family are not always the same. For example, fathers in Ireland were much more likely to be uncomfortable with their partner breastfeeding in public than someone else (Bennett et al., 2016).

Hypothesis 3: People with children will be more likely to support breastfeeding in public.

Hypothesis 4: People whose children were breastfed will be more likely to support breastfeeding in public.

Hypothesis 5: People whose children were breastfed in public will be more likely to support breastfeeding in public.

There may be demographic variables that are correlated with attitudes toward breastfeeding in public and awareness of these correlations may help with the planning of future public health campaigns. For example, men in the US were found to be less supportive of a stranger or their partner breastfeeding in public than women (Roche et al., 2015). Another study found that about half of New York City, NY, USA residents are not supportive of breastfeeding in public, but that younger and more educated people were more likely to support breastfeeding in public (Mulready-Ward & Hackett, 2014). It seems likely that there may be a generation gap in attitudes toward breastfeeding in public in the case of South Korea too.

Hypothesis 6: Different generations may have different attitudes about breastfeeding in public.

Based on rhetoric online about modesty that was tied in with religious ideals, we formulated our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: Religion may affect attitudes toward breastfeeding in public.

Campaigns to Encourage Comfort with Breastfeeding in Public

It has been suggested that, because issues like breastfeeding in public pose a barrier to optimal breastfeeding, aiming public health campaigns at the general public rather than only mothers and expectant mothers may be beneficial (McIntyre et al., 2001). Fathers’ prenatal education on breastfeeding has been found to have a positive impact on breastfeeding initiation (Wolfberg et al., 2004). There have been some recent attempts to improve people’s comfort level with breastfeeding in public. For example, young adults were found to be more comfortable with breastfeeding images shortly after watching a parody music video promoting breastfeeding in public (Austen et al., 2017). Posters aimed at the general public have also been shown to be helpful in rural parts of Canada (Vieth et al., 2016).

Korean Experience

Attitudes toward breastfeeding have been positively correlated to breastfeeding duration in Korea (Kang et al., 2015). Other factors have been linked to breastfeeding duration in Korea including delivery method, birth weight, maternal age (with mothers over 35 breastfeeding longer), education (with more educated women breastfeeding for a shorter time) (Hwang et al., 2006), income, maternal employment (both negatively correlated with breastfeeding), attending a breastfeeding class (Kim et al., 2002), the amount of prenatal care received (with more prenatal care being surprisingly correlated with lower durations) (W. Chung et al., 2008), stress (Ahn & Kim, 2015), and rooming-in (with mother’s who stayed in the same room as their baby after birth being more likely to still be breastfeeding 8 weeks postpartum) (Shin, et al., 2002).

The most common reasons women site for stopping include “a lack of breast milk (40.2%), reaching the right time to stop breastfeeding (26.0%), and returning to work (11.8%)” (Kang et al., 2015). Our work is focused on one aspect, attitudes toward breastfeeding in public, of a much more complex and multi-faceted issue. However, it is an area that has not been researched much in Korea.

Methodology

Survey Methodology

Several items related to breastfeeding experience and attitudes toward breastfeeding in public were added to a section titled “Public Health” on the omnibus Korean Academic Multimode Open Survey for Social Sciences (KAMOS). KAMOS is a nationwide, representative survey of Korean nationals over the age of 18 who are living in Korea. Our items were included on the survey conducted May 16, 2017-July 10, 2017. KAMOS uses the same two-stage probability sampling methods as Korean government- approved statistics; the primary sampling units were created by Statistics Korea (KOSTAT) based on the 2015 Census. All adult members of selected households were interviewed. The response rate was 65.8% (2000/3040). The sampling error was ± 2.2% p at 95% confidence level. Post-stratification weighting was performed on the basis of gender, residential area, and age.

Questionnaire Design

The survey items related to breastfeeding in public were meant to fully capture people’s attitudes and also create some basis for comparison to other countries. For this reason, we included one slightly modified item from the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) and another slightly modified item from the HealthStyles Survey. The item from IIFAS reads “Women should not breast-feed in public places such as restaurants” (De La Mora et al., 1999). The HealthStyles item reads “I am comfortable when mothers breastfeed their babies near me in a public place, such as a shopping center, bus station, etc.” (CDC, 2017). The examples of “public place” were different in the two examples mentioned above. We were concerned that, when these two items were asked consecutively on KAMOS, keeping the examples the same as they were in their sources may have caused some confusion, as if we were asking about whether a restaurant was an acceptable place to breastfeed compared to a shopping center or bus station. People’s attitudes may not be the same across all public places. For example, in Western Australia, it was found that 78.5% of people thought breastfeeding in a shopping center was acceptable, while only 68.2% found it acceptable in a restaurant (Meng et al., 2013). We considered asking about a variety of distinct public locations like Meng et al., but ultimately decided that modifying the IIFAS and HealthStyles items would best serve our purposes. Since we did not want to confuse our respondents by seemingly defining “public place” differently in two consecutive questions, we simply said “open, public place” for most of our items without defining the location more precisely. The first time “public place” was mentioned in the survey, we mentioned the examples used in both of the other questionnaires.

We considered the possibility, as mentioned above, that people could claim to not object to public breastfeeding while personally refusing to or, in the case of men, objecting to a close family member doing it. While people may claim to not be bothered by something, their willingness to do it themselves can often provide a more nuanced insight into their true feelings about the topic.

Our final attitude item asked people to consider a likely alternative to breastfeeding in public: allowing a child to cry and disturb others around him. We assumed that, when framed in this way, people would be more likely to support breastfeeding in public.

Another difference between our scale and the other scales mentioned (IIFAS and HealthStyles) was the use of a 4-point Likert scale instead of a 5-point Likert scale. While using a 5-point scale would have enabled a more direct and persuasive comparison between our survey and ones already conducted, we were concerned about a potential overuse of the neutral point. A study comparing results from a standard questionnaire and an unmatched count technique suggested that there may be some social desirability bias affecting the way people answer questions about their attitudes toward breastfeeding in public (Lippitt et al., 2014). Johns (2005) found that using a 4-point scale rather than a 5-point scale increases validity when people are likely to have a basis for an opinion but may be hesitant to express an unpopular opinion. The use of a 4-point scale to measure opinions about breastfeeding in public, given the likelihood of social desirability bias, especially during a face-to-face survey, seemed to be appropriate.

Analysis

Where appropriate, statistical analysis, either linear regression or ANOVA, was applied to the five questions related to attitudes toward breastfeeding in public (Question 31 in the questionnaire; see Appendix) to test for statistical significance. Since one of these five questions was only for men and one was only for women, there were no respondents who answered all five questions. Therefore, each item was analyzed independently. The 4-point Likert scale was considered as a “continuous” response variable in our analysis.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

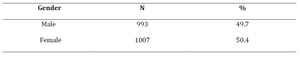

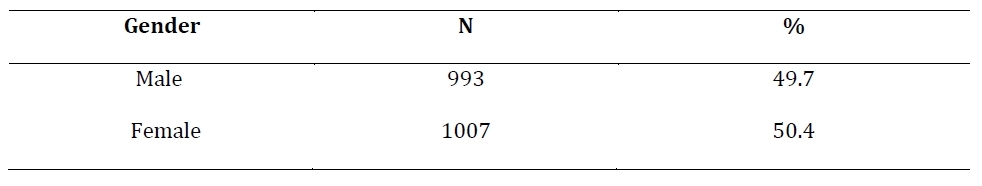

Of the 2,000 respondents, 50.4% were female.

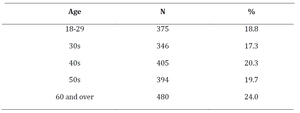

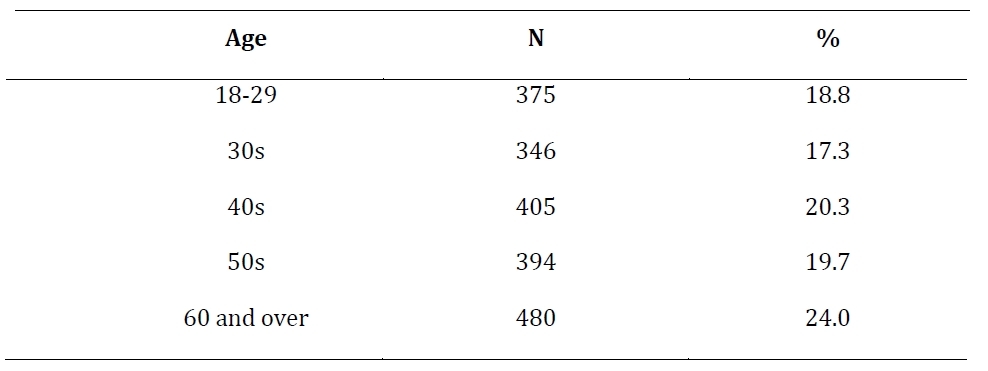

The ages of participants was spread as expected as18.8% were ages 18-29, 17.3% were in their 30s, 20.3% in their 40s, 19.7% were in their 50s, and 2a4.0% were 60 or older.

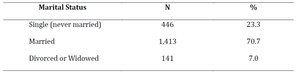

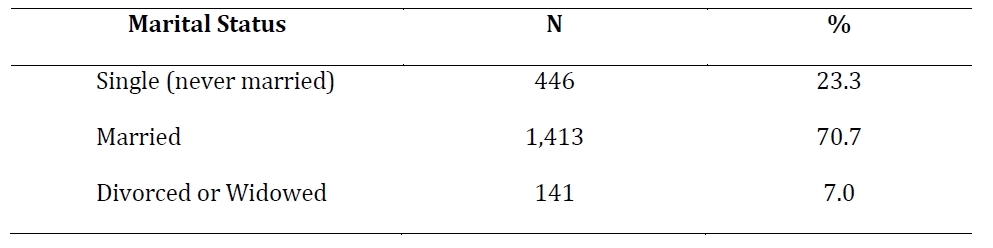

The majority (70.7%) were married, with 23.3% single (never married), and 7.0% divorced or widowed.

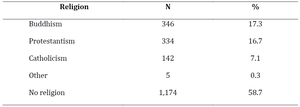

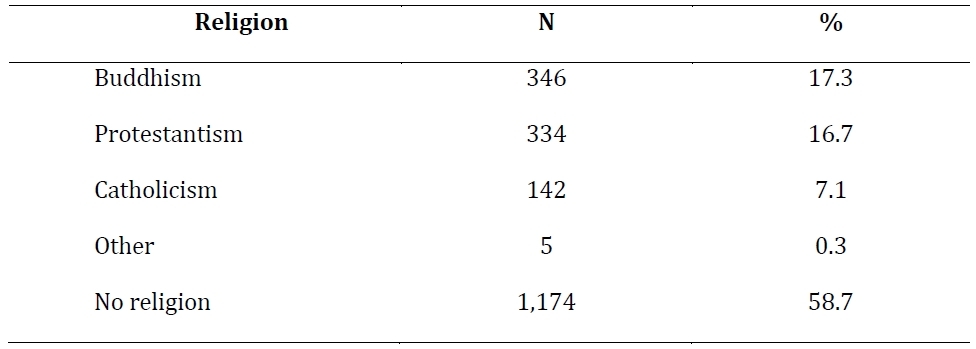

More than half did not practice any religion (58.7%), while 17.3% were Buddhist, 16.7% were Protestant, 7.1% were Catholic, and 0.3% practiced another religion.

Information was also collected about the region of participants’ hometown and current town, the size of their current town, education level, employment status, family size, income level and perceived social class, and type of home (apartment, single family house, etc.).

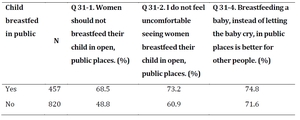

Attitudes Toward Breastfeeding in Public

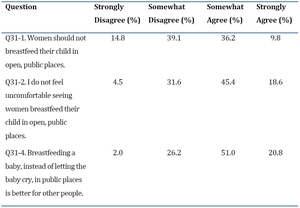

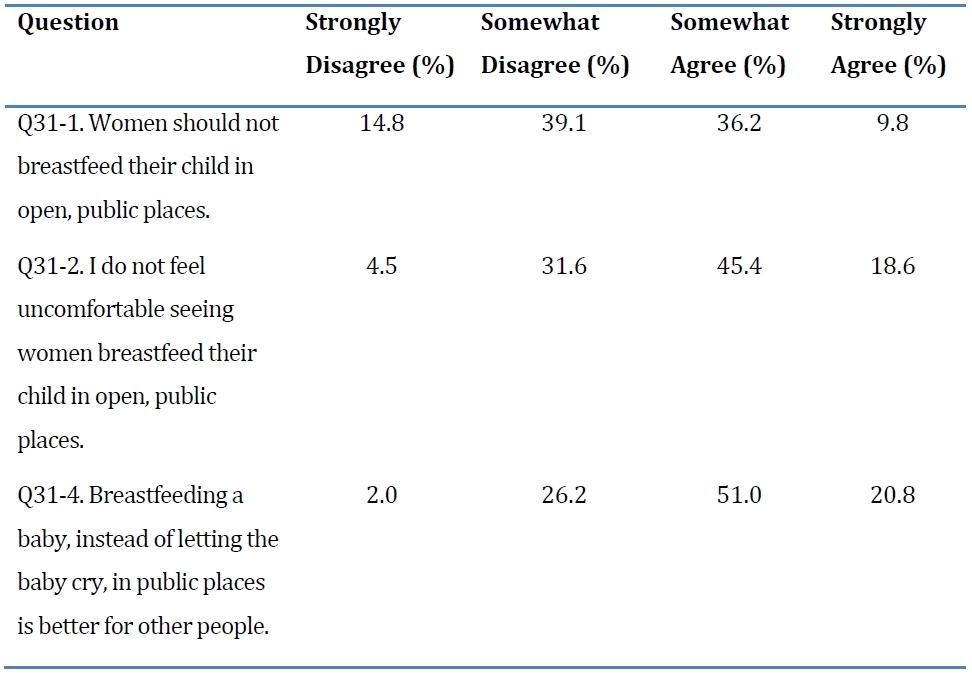

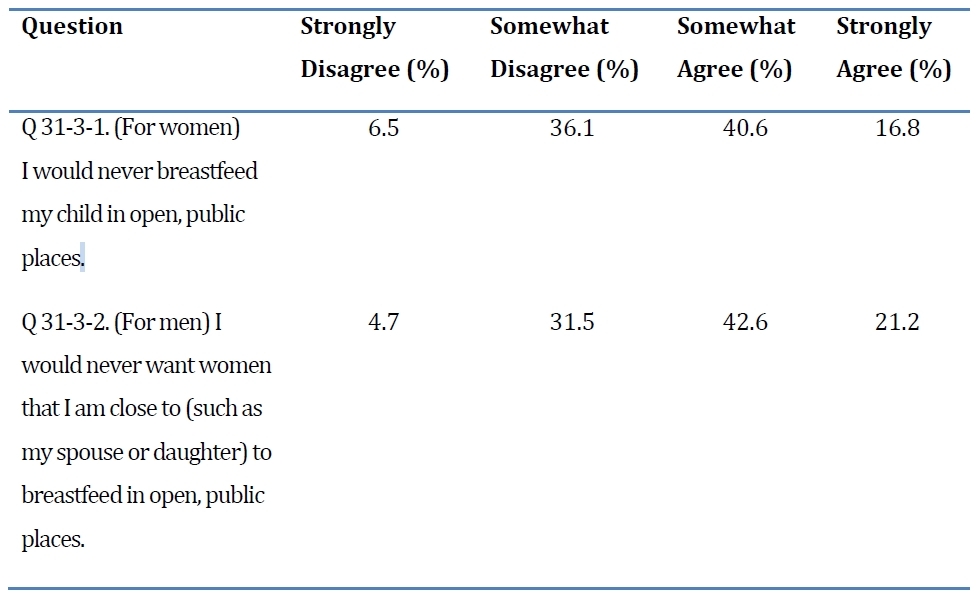

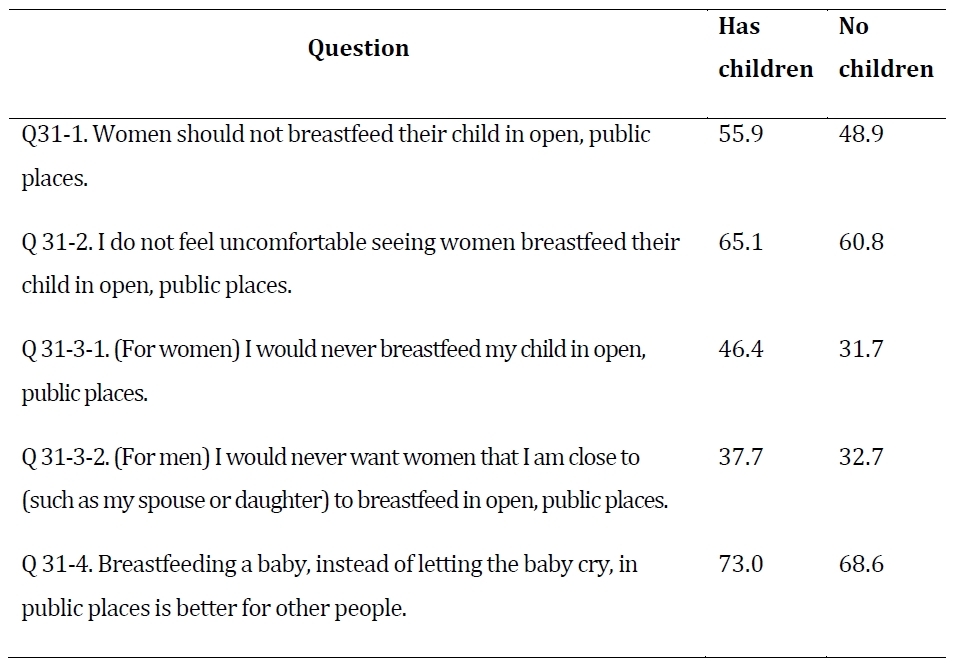

A majority of Koreans expressed positive attitudes to breastfeeding in public generally. That is, a majority either disagreed (1 or 2 on a 4-point scale) with the statement “Women should not breastfeed their child in open, public places” (53.9%) and agreed (3 or 4 on the 4-part Likert scale) with the statements “I do not feel uncomfortable seeing women breastfeed their child in open, public places” (64.0%) and “Breastfeeding a baby, instead of letting the baby cry, in public places is better for other people,” (71.8%). Most people did not express strong opinions, that is, they chose either 2 or 3 on the scale instead of 1 or 4. As predicted, positive attitudes were highest when the issue was framed with the alternative of letting a child cry in public rather than feeding him.

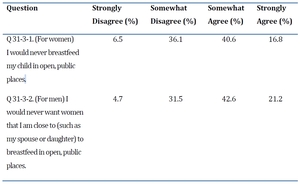

However, despite these generally positive attitudes, the majority also said that they would not breastfeed in public (57.4% of women) or, in the case of men, would not want a close female relative to do so (63.8% of men).

Hypothesis 1: Cultural Attitudes and National Breastfeeding Rates

Testing Hypothesis 1 presents some challenges. There is no perfectly comparable data. As discussed above, slight changes in the question wording can have an effect on responses. In addition, even when a Likert scale was used with an almost identical question, as in the case of the HealthStyles Survey in the USA, the scale was not the same; the HealthStyles Survey used a 5-point scale, while KAMOS used a 4-point scale. So, there was a neutral point available to American respondents that was not available to Korean respondents. There may be some non-attitude bias, that is, it is possible that Koreans who may have chosen a neutral point if it had been available were forced to choose a side, or conversely, there may have been Americans who actually had an opinion that they would have expressed if they had felt compelled to decide one way or the other. If we divide the 23.13% who chose the neutral point in the USA equally, the percent of Americans who agree with the statement “I am comfortable when mothers breastfeed their babies near me in a public place, such as a shopping center, bus station, etc.” would increase from 57.75% to 69.315%, which means it would reverse who was more comfortable witnessing public breastfeeding: Koreans or Americans. This closeness remains for the actual breastfeeding durations as well. It is not possible to say who has better breastfeeding rates: Korea has a higher initiation rate of 96.1% compared to America’s 81.1% and remains slightly higher at 6 months (55% to 51.8%), but Americans exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months is higher than Koreans (22.3% to 9.4%). Given that neither country can be said to clearly have the better breastfeeding rates and durations and the comfort levels of breastfeeding are similar, a comparison for the purpose of ascertaining the effect of attitudes about breastfeeding in public between these two countries does not seem feasible.

While not exactly asking about “comfort,” a survey from China asked respondents if they feel embarrassed when they see someone breastfeeding in public; 47% said yes (Zhao et al., 2017), which implies 53% did not feel embarrassed. Based on this, we can say that more Koreans and Americans feel comfortable with others breastfeeding in public than Chinese people. Americans and Koreans have higher breastfeeding initiation rates and higher breastfeeding rates at 12 months compared to China, which supports Hypothesis 1. However, China has higher exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months than Korea (although they are slightly lower than the exclusive breastfeeding rates in the USA).

We also attempted to compare the question about the acceptability of breastfeeding in public. Some of the areas we could find data for were smaller areas rather than whole countries, such as Western Australia and the city of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada. The survey from China also had a similar question. All three of those surveys showed more positive attitudes than Korea did. Ottawa and Western Australia both showed better rates of any breastfeeding at 6 months compared to Korea and Western Australia had better breastfeeding rates at 12 months, lending some support to Hypothesis 1, but did not do better than Korea in any of the other measures.

Hypothesis 2: Attitudes and Breastfeeding Duration

Women who disagreed with the statement “I would never breastfeed my child in open, public places,” that is, women who were willing to breastfeed in public, were more likely to breastfeed for longer, with 62.2% of those who breastfed for 25 months or longer and 56.4% who breastfed 19-24 months disagreeing. These results were statistically significant; among mothers with some (at least 1 month) experience breastfeeding, linear regression showed that those who disagreed with that statement breastfed for longer durations (adjusted R-squared = 0.01088). Surprisingly, mothers who did not breastfeed at all were (hypothetically) more willing to breastfeed in public (53.6%) than mothers who breastfed for shorter durations (42.2% for 1-6 months feeding; 40.1% 7-12 months, and 47.6% for 13-18 months), but generally, those with no breastfeeding experience (mothers who did not breastfeed and women who are not mothers) were less likely to be willing to breastfeed in public than women who breastfed (37.3% vs. 45.4%).

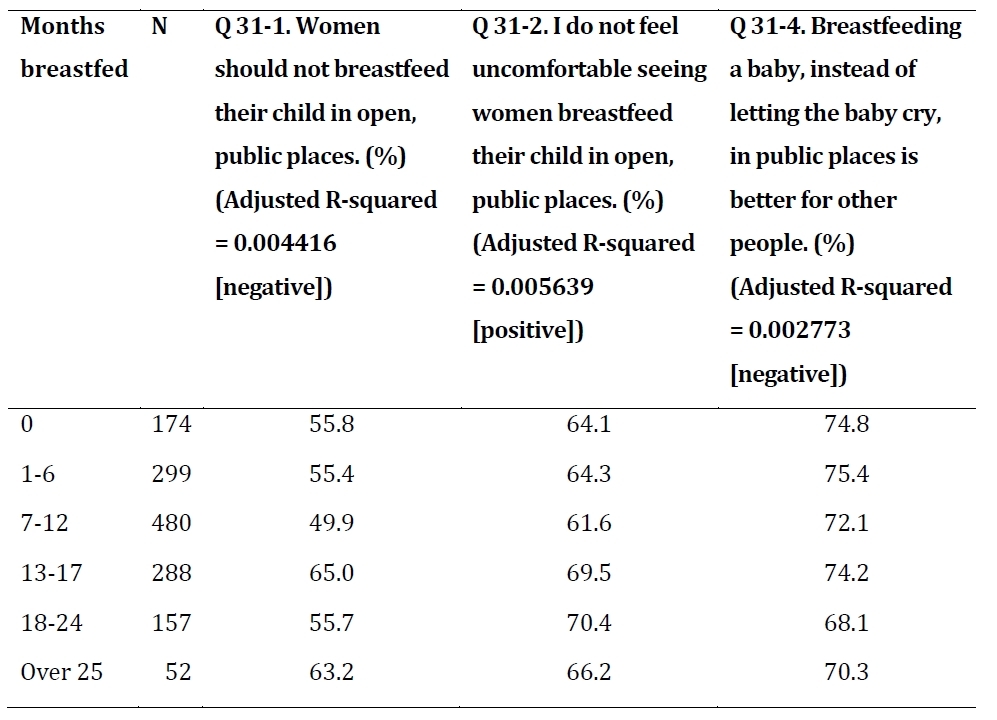

The positive association between a willingness to breastfeed in public and the duration of breastfeeding supports Hypothesis 2. A similar pattern was faound with men and their attitudes toward their partner feeding (adjusted R-squared = 0.01061). However, it should be noted that the relationship between breastfeeding duration and attitude toward breastfeeding in public was not always so clear. All of the attitude questions had a statistically significant relationship to duration of breastfeeding (among parents whose children were breastfed). Most were in the direction that supported Hypothesis 2, except the final item: “Breastfeeding a baby, instead of letting the baby cry, in public places is better for other people,” that is, people who breastfed for shorter durations were more likely to agree with the statement than those who had breastfed for longer durations. This relationship was not as strong as the others (adjusted R-squared = 0.002773).

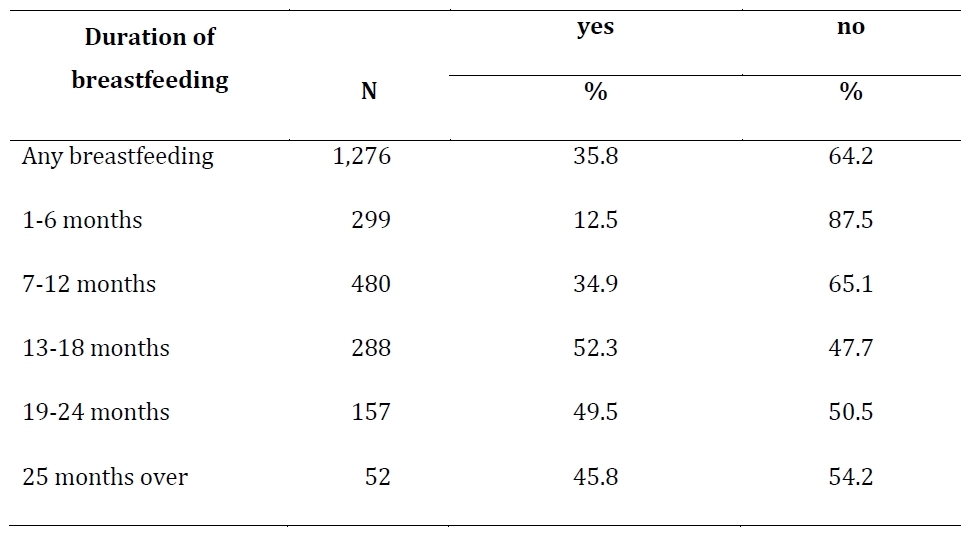

Actual behaviors toward breastfeeding in public also seem related to breastfeeding duration, with parents whose children were breastfed in public being more likely to have breastfed for 13 months or longer. This behavior may even more clearly reflect people’s true opinion about whether they would breastfeed in public than the question about their intention to breastfeed in public (31-3 discussed above). Nevertheless, this relationship does not prove that breastfeeding in public necessarily enabled a longer duration of breastfeeding; it is also possible that, as mothers breastfed for longer, the likelihood of them being in a situation where breastfeeding in public felt necessary increased. However, whatever the cause of this relationship, tolerating or even encouraging breastfeeding in public seems like an important element toward increasing breastfeeding rates (i.e., if breastfeeding in public allows women to breastfeed for longer, we should encourage it, or if women who breastfeed for longer are more likely to breastfeed in public and we want longer breastfeeding durations, we should also support breastfeeding in public).

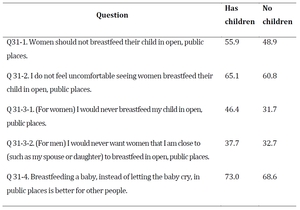

Hypothesis 3: Parenthood and Attitudes

As predicted, people who have children have more positive attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. The largest difference was in women’s willingness to breastfeed in public (14.7 percentage points). This suggests that women may change their attitudes and behavior after giving birth and that parents may be sensitive to the needs of children and families. Using linear regression analysis, all attitudinal questions were found to be significantly related to the number of children someone had in the direction expected (p <.05), that is, people with more children were more likely to support breastfeeding in public. Hypothesis 3, that Koreans with children were more likely to have positive attitudes about breastfeeding in public, was supported by the results.

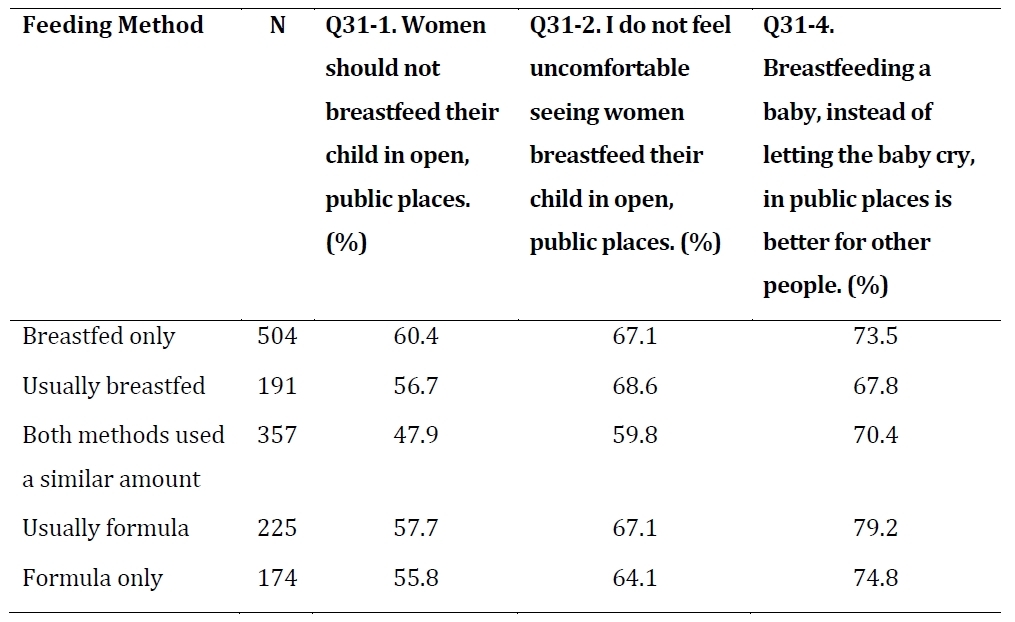

Hypothesis 4: Breastfeeding Experience and Attitudes

The method parents used to feed their baby was also related to their attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. It may be surprising to note that parents who fed their children formula only or mostly formula were not the most negative toward breastfeeding in public. Those who used both feeding methods a similar amount were the most negative. This may be explained by these families feeling the greatest level of flexibility; if both feeding methods are used equally, it may seem easy to avoid breastfeeding in public. Families that used only one or mainly one feeding method may have been more sympathetic to the difficulties of using a bottle in public for a primarily breastfed baby.

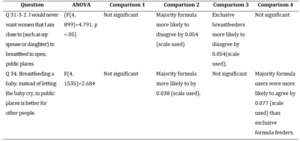

An ANOVA test showed the way people fed their children had a statistically significant effect on attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. Then comparisons were made between different variations between the five groups. There were significant differences on all questions, but not between all groups and all questions. The comparisons made were:

Comparison 1: (Breastfed only & usually breastfed) vs. (Equal breastfeeding and formula, formula more, & exclusively formula)

Comparison 2: (Breastfed only, usually breastfed, and equal breastfeeding and formula) vs. (formula more & formula exclusively)

Comparison 3: (Breastfed only) vs. (Breastfed more)

Comparison 4: (Formula more) vs. (Formula only)

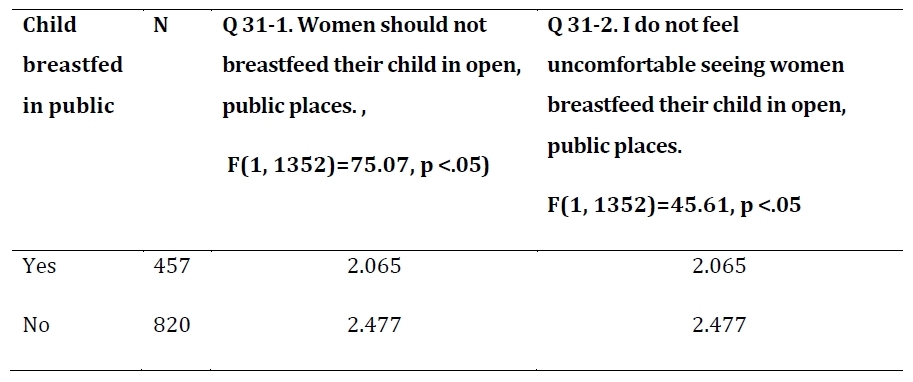

Hypothesis 5: Experience Breastfeeding in Public

Among respondents who were mothers who had ever breastfed, 245 had the experience of breastfeeding in public while 414 did not; 212 fathers had children who were breastfed in public, while 406 fathers of breastfed children said their children were not breastfed in public. As predicted, parents whose children had been breastfed in public were more positive about it, generally. An ANOVA test showed no significant difference in the final attitudinal question, “Breastfeeding a baby, instead of letting the baby cry, in public places is better for other people,” but all other attitudinal questions were significantly related to whether the respondent’s child had ever been breastfed in public (p<.05).

It was surprising that 37.6% of mothers who had previously breastfed a child in public said that they would not do so. This suggests that breastfeeding in public in Korea may have been an uncomfortable experience. Still, mothers who had breastfed in public were significantly more likely to say that they would do so (F(1, 791)=79.19, p<.05). When mothers rated the statement, “I would never breastfeed my child in open, public places,” on a 4-point scale, where 4 was strongly agree, those who had breastfed in public had a mean score of 2.264, compared to 2.78 among mothers who had not breastfed in public.

Men whose children had been breastfed in public were less likely to wish that women they were close to not breastfeed in public, with fathers whose children had been breastfed in public having a mean score of 2.417, and fathers whose children had not been having a mean score of 2.897. Men whose children were not breastfed in public were also more likely to have strong opinions. The causality of this is not clear. It may imply that men have a significant influence on their wife’s decision to breastfeed in public, so that those who object more strongly have partners who are less likely to breastfeed in public. On the other hand, it could also mean that after witnessing their wife breastfeed in public, men became more comfortable with the idea.

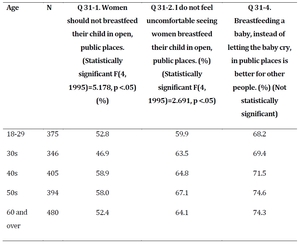

Hypothesis 6: Generational Differences

There appeared to be generational differences. In general, age was positively correlated with attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously; age was also positively correlated with having children, which, as discussed above, was positively correlated with attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. In addition, breastfeeding rates in Korea decreased dramatically in the second half of the 20th century as Korea became more industrialized and wealthier. This was reflected in our results, as parents who are now age 60 or older were much more likely to have exclusively breastfed their children (64.6% compared to 11.4% of parents who are now in their 30s)[1] or to have mainly breastfed their child, including both exclusive breastfeeding and mainly breastfeeding with some supplementation with formula (78.8% compared to 20% in their 30s). Parents in their 30s were much more likely to exclusively formula or mainly formula feed (52.2% compared to 8.6% who are in their 60s).

Age was also positively associated with having had a child who was breastfed in public, although the difference was not as dramatic (39.6% of parents with experience breastfeeding in the 60 and over age group had breastfed in public compared to 28.2% in their 30s). It should also be noted that, of the 10 parents with breastfeeding experience who were under 30, 57.6% had breastfed in public, suggesting that both breastfeeding rates and breastfeeding in public are on the rise, but with such a small number of parents in this age group, the results should not be generalized too much.

The older generation was also more likely to breastfeed for longer durations, with 57.3% of breastfeeding parents over the age of 60 having breastfed for 13 months or longer, compared to 18.5% of parents in their 30s. Breastfeeding parents who are now in their 60s breastfed for an average of 16.71 months compared to 8.83 months of parents in their 30s.

Despite being more likely to have had a child breastfed in public, those over 60 were not the most likely to disagree with the statement that women should not breastfeed in public (52.4%); people in their 40s and 50s were the more likely to disagree (58.9% and 58.0% respectively). People under 30, who were also more likely to not be parents and so may have less experience seeing breastfeeding, are the most likely to feel uncomfortable when seeing someone breastfeed in public (40.1%). There were significant differences in the responses of those age 18-29 compared to 30s and over in the first 4 questions, with the older group expressing more positive attitudes about breastfeeding in public. There were no statistically significant differences by age on the final question about the choice between letting a child cry or breastfeeding in public.

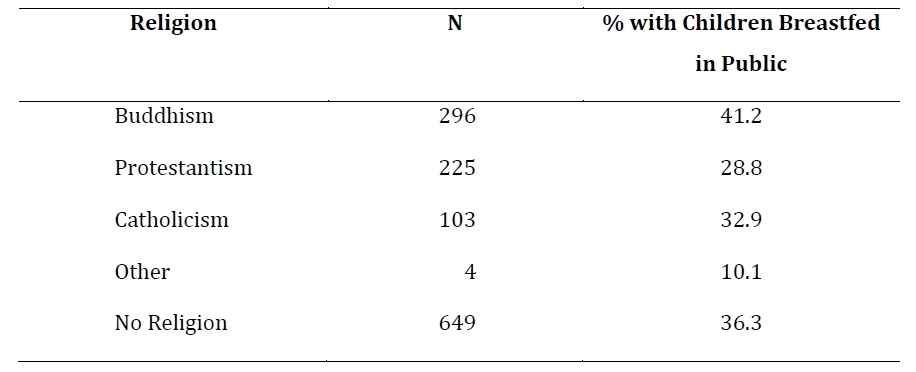

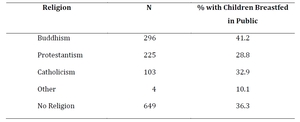

Hypothesis 7: Religion and Attitudes

Religion seemed to be related to breastfeeding in public attitudes and behavior. Buddhists were the most likely to have breastfed in public (41.2%) and, of the major religions in Korea, Protestants were the least likely (28.8%).

Part of the difference in attitudes toward breastfeeding in public may be explained by the parenthood factor: parents are more likely to have positive views, as noted above, and Buddhists included in this survey were more likely to be parents; 91.7% of Buddhists interviewed had at least one child compared to 77.5% of Protestants, 82.8% of Catholics, and 64.1% of those with no religion. However, when looking at only parents and their experience breastfeeding, the difference persists, which supports Hypothesis 7.

Christians (Catholics and Protestants combined) were less positive toward breastfeeding in public than Buddhists on two of the questions: 31-1 (about whether women should breastfeed their child in the open, by 0.05288) and 31-3-1 (about women’s intentions to breastfeed in public, by 0.06230). This may imply, as expected, that Christians in Korea have stricter personal definitions of modesty compared to Buddhists and those with no religion. However, there was no statistically significant difference between Christians and Buddhists on the questions about comfort when seeing others breastfeed in public or about breastfeeding being a better alternative to letting a child cry in public. This suggests that, in Korea, Christians apply their personal modesty code mainly to themselves rather than to others. There were no significant differences between Catholics and Protestants or between those with no religion and those with a religion.

Discussion, Conclusion, and Future Research Directions

Our results show that, although the majority of Koreans are not bothered by seeing others breastfeed in public and would prefer to see a breastfeeding baby in public rather than a crying one, they are unwilling to breastfeed in public themselves. Our results also show breastfeeding in public is correlated with longer durations of breastfeeding. Of course, it is not certain whether this is a causal relationship. It is possible that women who intend to breastfeed for longer may also be more willing to breastfeed in public or that there is some other factor affecting both duration and willingness to breastfeed in public. However, based on previous research from other countries, it seems likely that women

who feel comfortable breastfeeding in public will continue to do so for longer durations. This is further supported by many women citing insufficient quantities of breast milk as a reason for discontinuing breastfeeding; skipping feeds (e.g., due to being in public and unwilling to breastfeed the baby until getting home) will decrease a woman’s milk supply. Scott et al. (2014), found that breastfeeding in public was more related to perceived cultural norms than the mother’s personal attitudes toward seeing breastfeeding in public. This may also be the case in Korea; while Koreans do not object to breastfeeding in public, they may not perceive it as a culturally normal thing to do and so are uncomfortable doing it.

A next step in our research would involve conducting a public health campaign to normalize breastfeeding in public. Our survey items could then be repeated in a few years to see if breastfeeding rates, durations, and attitudes toward breastfeeding in public change. A few things should be taken into account in planning this kind of campaign. Korean culture emphasizes caring about other people’s comfort. It may be that, while people are not offended by seeing breastfeeding in public, they fear offending others and so are not willing to do so themselves. It may therefore be useful to emphasize in future public health campaigns that the majority of Koreans would not be uncomfortable seeing breastfeeding in public and would prefer it to hearing a child cry. It may also be useful to consider the demographic variables related to breastfeeding attitudes and behavior when planning a campaign. For example, young, educated, and childless people were less likely to have positive attitudes toward breastfeeding in public; normalizing breastfeeding in public may involve campaigns directed at these groups.

In addition, we would like to continue to pursue international comparisons. At this time, we did not have any perfectly comparable data; question wording and scales were different from country to country. However, we hope to eventually have comparable data. This kind of cross-cultural comparison has many uses. Having data about perceptions in more breastfeeding-tolerant cultures may help support those in cultures less tolerant of public breastfeeding, (i.e., women may feel more empowered to assert their right to breastfeed their baby in public if they can point to other countries where it is accepted as a normal part of life). Cross-cultural comparisons also help improve understanding how different attitudes may influence breastfeeding rates and therefore help with future efforts to meet the WHO guidelines worldwide.

Biographical Notes

Sarah Prusoff LoCASCIO is an associate editor and journal coordinator for the Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research (AJPOR) and researcher at the Center for Asian Public Opinion Research & Collaboration Initiative. She earned her master’s degree from Indiana University in Bloomington, IN, USA and her bachelor’s degree from Bard College at Simon’s Rock in Great Barrington, MA, USA.

She can be reached at Center for Asian Public Opinion Research & Collaboration Initiative, Chungnam National University, Department of Communication 99, Daehak-ro, Yuseong- gu, Daejeon, 305-764 or by email at <sprusoff@umail.iu.edu.>

Hee Won Cho is affiliated with Department of Psychology, College of Social Science, Seoul National University, Republic of Korea. She can be reached by email at joys0214@gmail.com

Date of submission: 2017-08-21 Date of the review result: 2017-08-27 Date of the decision: 2017-08-28

Only 11 respondents under the age of 30 were parents.

_to_b.jpg)

_to_b.jpg)