Introduction

Gender inequality in education is a classic issue and a product of gender stereotypical notions, which make people think woman does not require (more) education since she has to play her gender roles as a full time mother, a devoted full-time housewife, a skillful cook, and a faithful lover. Stereotypes as such put women in an inferior status compared to her male counterpart and result in gender inequality, woman’s subjugation, and gender division of labor. Socially constructed gender identity creates a male-female hierarchy. Education, training, and skills have been sometimes been thought to be of little value for women.

Thus, women can suffer from worse poverty due to a lack of educational qualifications for jobs and to patriarchal social practices. Women remain financially dependent on men and considered inferior to them. In Lee’s words, “patriarchal restrictions on women’s capacity earning…widows are the poorest among the poor” (2006, p. 1). Lee’s critical comment reflects the patriarchal system that deprives women of their rights to education, resulting in a lack of earning opportunities. It is also an attempt to imply how education has a strong relationship with women empowerment as education can enhance women’s capacity to deconstruct the unfair traditions and norms and is one of the most effective mechanisms to enable social mobility.

It is important to note that, historically, some women had the chance for education, but most of the time only those from the upper class and those with religious obligations could enjoy such social privilege. For instance, nuns were educated and allowed to teach new novices. Upper class people’s daughters’ education could enhance their marriage potential. Thus, the purpose of education was more likely “to produce skilled a housewife than an educated person” and education was more “moral rather than intellectual”, (Parker, 1972). In other words, such education eventually reproduced the social class and worsened the exploitation of women. From the conflict theoretical point of view “education served the interest of the dominant class” (Saha, 2001).

Some countries such as the United States, South Korea, and India have initiated gendersegregated classrooms and gender-segregated schools with clear and convincing objectives to avoid gender stereotypes in classroom. However, a study indicated that “gender segregated classrooms reinforced and strengthened gender stereotypes” (Fabes et al., 2013). This means that separating people based on gender to mitigate gender stereotypes does not necessarily produce better outcomes.

Even though the issue has been just slightly improved over recent years, there is a lack of reliable data on women’s leadership. However, a recent study that was conducted in South Asian countries revealed that women viewed leadership as associated with masculinity and it was not popular among women (Morley & Crossouard, 2016). Underrepresentation of women in education leadership definitely leads to a lack of strong support from their representatives at the top policy making levels. To tackle gender stereotypes, there is urgent work, which needs to be done, including revision of curricula, rethinking school structure, closing the rural-urban development gap, policy initiations, and public awareness (Morley & Crossouard, 2016).

Theoretical Frameworks

Sociological perspectives define education as “a social fact, a process, and an institution, having a social function and being determined socially” (Shimbori, 1979). The concept “social facts” embraces terms including values, cultural norms, and social structures. Durkheim thought that the function of education was to transmit social values and norms; these norms and values bring about essential similarities, co-operations, and social solidarity (Haralambos & Heald, 2003). Education acts as a socializing agent and connection between family and society. What students literally learn during the schooling process is the self-preparations for adult roles, a transaction, and a shift in roles.

To feminists, equal distribution of educational opportunities opens the door for women’s empowerment. Gender division of labor gives excuses that women do not need to acquire more education, more knowledge, and skills. What women need to do is to perform their gender roles as expected by society. Women learn to replicate their roles from mothers and reproduce and reinforce gender stereotypes. They also try to internalize their roles when they become mothers through the reproduction of their mothers’ behaviors and roles through everyday life experiences (Davis, 2012). More importantly, gender socialization lessons have been taught by mothers to their daughters.

Equal opportunity in education becomes essential, as it has the potential power to liberate women from gender roles and improve their social status. Male subjugation over women should be eliminated and women’s active partaking in their natural rights should be strongly motivated (Wollstonecraft, 2014). Women should have the same potential as a men do. Wollstonecraft believed educated women would significantly contribute to society’s welfare. Tong also states that a woman needs to be autonomous and free herself from being a slave to her passion, her husband, and children (Tong, 2014). This view is a clear argument against gender roles played by women and imposed on women by family, school, and media. However, sociologists of education think that liberal feminists and democratic reforms have failed to essentially solve the social inequality problems (Arnot, 2002). Such failure gives room to reproduce deeper and stronger social class stratification, unfair exploitation, and mistreatment of women.

Many educated women are kept at home and expected to perform their gender roles. Furthermore, based on various studies, in South Korea and India, sex role expectations prohibit women from participating in the workforce by making education one of the most required qualifications for a girl’s marriage (Cho, 2012; Gautam, 2015). Thus, both men and women are caught in gender stereotypes and sex role expectations from an early age through the socialization process because the value of education was misinterpreted as a passport to marriage and not an empowering tool.

On the one hand, culture and religion eventually shape ways of thinking, actions, and behaviors of individuals; therefore, gender inequality in education is seen as a byproduct of culture and religion as well. Some religious beliefs restrict women’s right to education and employment (Cooray & Potrafke, 2011; Norton & Tomal, 2009). Social class status has an effect on women’s educational opportunities, and families, most often, prioritize investment in their male children’s education, although there has been a decrease in sexist views toward women’s education and employment (Pavolini & Ranci, 2010; Spitze, 1988). Then again, reducing sexist views against women’s education and employment can be driven by the inevitable needs of family’s economic survival in a changing society, especially among the lower class.

In short, theories of gender inequality in education involving the feminist theories, which see women are constantly exploited, oppressed, subjugated, and stereotypically socialized, state that social institutions are responsible for women’s exploitation.

Women’s Education and Employment

Education as an institution plays the role of a socializing agent, qualified workforce producer, and so on. In other words, education is inevitably linked to employment. However, a large percentage of educated women are still unemployed or employed in traditional occupations, which women are generally believed to do better. For instance, expecting that female teachers are good at caring for children, preschools have more female teachers than male teachers. Previous studies show that more women are employed as early childhood education teachers than men. “Social status, stereotypes, and cultural expectations” result in few men being attracted to the occupation of early childhood education teacher (Gamble & Wilkins, 1998, p. 64). From this literature, it seems women’s employment only shifts her role from nurturing and caring for children at home to the workplace.

The studies have drawn our attention to gender stereotypes regarding proper roles played by women. Negative portrayal of women regarding gender roles are shown through media such as movies, children’s programs, advertisements, plays, etc. where women are usually portrayed as mothers taking care of children, nurturing children, and feeding children (Bretl & Cantor, 1988; Das, 2011; Tsai, 2010). From these theoretical perspectives, we can see how stereotypes about women’s roles can have both direct and indirect influences on societies (Shanahan & Morgan, 1999). Therefore, the media is also one of the three important socializing agents today.

To feminists and sociologists, equal opportunity in education provided to women is an effective tool to empower them, make them independent, and reduce gender inequality to a large extent. Furthermore, women’s educational qualifications can have important effects on childcare, child education, and women’s personal health awareness beyond acting as a promising tool to empower women, women’s education can be a motivating force behind child’s education, childcare, family income, and social benefits. A similar finding was found in Australia about the effects of parents’ education level, which can influence the education completion of both female and male children (Chesters & Watson, 2012). It is right to say that if you educate a woman, she will surely educate her children tomorrow and become a role model for other women.

However, after education attainment, societies need to put women in the job market because many scholars believe education should be linked to improved employment opportunities. In many cases due to sexual division of labor in a family, women were placed in gender specific occupations even in public sectors. Women were thought to not be as productive as their male counterparts. Women were believed to not be ready, not productive, and not motivated (Core, 1994). Similarly, maternity leave is thought to decrease a company’s productivity. During the economic crisis period, Korean women got fired faster than men. In the 1997 economic crisis, female workers’ lay off rate was 1.5% higher than men (Cho, 2012). Furthermore, the pay gap among the mothers and nonmothers is significantly different (Crittenden, 2011).

The pay gap is another issue that women are facing in the workplace. Though women perform the same jobs and have the same positions, they still get less pay.

Loucopoulos et al. (2002) highlighted the results from their analysis on classification models (linear discriminant function “LDF,” quadratic discriminant function “QDF,” mixed-integer programming model “MIP,” mixed Integer Quadratic Program “MIQP”) that the pay discrimination in the workplace can create gender classifications. In addition, work benefits were also selectively distributed. In some cases, promotion is not based seniority and meritocracy, but based on gender. Such issues restrict women’s career development (Baxter & Wright, 2000). Women can face these almost common problems: discrimination, unequal pay, sexual harassment, and a glass ceiling.

As mentioned earlier, in order to have equal status comparable to men, women need education and skills. Education is not only for the job, but also for the betterment of their everyday lives. Educational, family, and economic changes contribute to the increasing trend of gender equality (Cotter et al., 2011). However, instead of improvement in opportunity for women in education, a considerable percentage of educated women in developed countries are missing from the labor market, which is the result of men being afraid of losing the authoritative roles and power (Spitze, 1988).

Cultural and religious factors are among the factors undermining women’s opportunities in education. This issue leads to discrimination against women in receiving education and freedom to work (Becker & WoBmann, 2008; Cooray & Potrafke, 2011).

In recent decades, gender inequality has been reduced, and gradually there seems to be promising steps for woman having an equal chance in education; however, gender stereotypes have still significantly influenced women’s career and class mobility. The theories and literature provide an overview on gender inequality in education and education related issues.

Objective

The objective of this study is to explore the current perceptions of the public on women’s higher education and employment.

Data and Empirical Strategy

We used the data from 60 countries that the World Values Survey using random sampling techniques with the objective to find what the things/choice that people value and was published in 2016 (Inglehart et al., 2014). The World Values Survey questionnaire included 258 variables. However, we excluded irrelevant variables and included only those related to our study. We took eight independent social-demographic variables: gender, age, social class, income, education attainment, religion, marital status, and number of children.

We recoded two dependent variables, which are the perception on whether a university education is more important for a boy than a girl (V52) and whether being a housewife is just as fulling as working for pay (V54). We used SPSS to re-code and compute by reversing the scales of the question from 1-strongly agree, 2-agree, 3-disagree, 4-strongly disagree to 4-strongly agree, 3-agree, 2-disagree, 1-strongly disagree.

For the independent variables we re-coded and computed as following:

Gender (V240): 1=>0-male, 2=>1-Female

Recoding was not done on the Age (V241) and Highest level of Education (V248)

Social class (V238): 1=>5-Upper class, 2=>4-Upper middle class, 3-Lower middle class, 4=>2-Working class, 5=>1-Lower class

Calling themselves as (V147): 1.Religious person, 2 and 3=> 0-No religion/atheist.

Marital status (V57): 1=>0-married and living together as married, "3-divorced, 4- seperated, 5-widowed, 6=single =>1).

Children (V58): 0-No child, 1-from one child to eight or more.

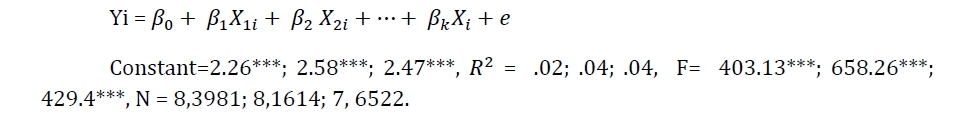

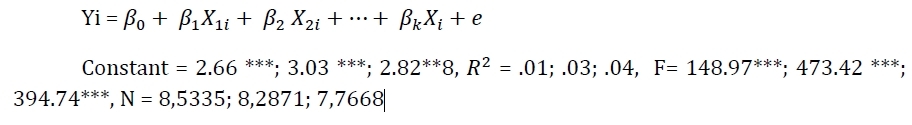

After computing and recoding, we constituted the multiple regression analysis using a hierarchical model structure to find out the correlation between our new formulated dependent variables and new independent variables. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 were used to predict the correlations. We have regression equation models as

Demographic Details

The results of this study are based on multiple regression analyses that were executed on a sample of 90,350, of which 48.03% (N= 43,391) were male, 51.87 % (N=46,878) were female, and 0.1% (N=91) were missing values and unknown.

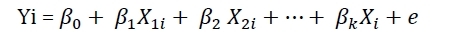

The findings (Table 1) on the influence of socio-demographic factors on perceptions on women’s education have indicated a strong statistical significance with all socioeconomic backgrounds of respondents in all three hierarchical models (*** < .001), except the social class variable which changed its significant value from p < .001 in the first model, to p < .01 in the second model, and p < .05 in the third model.

In the first table, there are three stages of hierarchical models,

In Table 2 , all variables have a strong statistical significance with p < .001 in all three hierarchical models. This means that any change in the value of independent variables, will trigger a change in the dependent variables’ values.

In the second table, there are three stages of hierarchical model,

Discussion

According to the findings, social class, income, and age do not have significant influence on attitudes of the public toward women’s university education and employment. However, gender, level of education, being a religious person, and marital status has a strong influence on the dependent variables, especially being a religious person.

Gender

Education is always viewed as a solution to social problems, including eradication of gender discrimination. Moreover, education plays a vital role in promoting social values and forming opinions to bring about gender equality (Council of Europe, 2016). The findings on women’s education showed strong statistical significance in all three regression models (p< .001). Thus it indicated that women are more likely than men to hold stereotypical attitudes towards the significance of university education and believe that university is more important for males than females. This theoretically means that they are still caught in sex role expectations and gender stereotypes. One of the important factors which might influence women’s decision to pursue higher education is the male supremacy in the family, where men are exercising decision making power (Gautam, 2015). The findings reflected how society is still governed by the patriarchal system and women are still considered dependent and subordinate to men. Women are still the victims in the suppressive social system, which they may not be fully aware of.

Age

In this study, the youngest respondent is 16 and the oldest is 99. Based on statistical significance in all regression models, younger respondents were more likely to have a sexist perception toward women’s education and employment. This is due to factors such as exposure to media, education, culture, society, and other early socializing factors (Browne, 1998). There are people carrying out the practices of gender stereotype without realizing they are. Such practices influenced adolescents’ future education and career choices to a large extent (Ginevra & Nota, 2015).

Marital Status

University education is a passport to employment and women’s empowerment. Denying a woman higher education can mean denying her financially independent status, by imposing or accepting the gender role ideology where man is a breadwinner and woman is a housewife. Men are reluctant to allow women to receive an education, but women are indecisive about accepting higher education as the results of culture, gender stereotypes, and social norms.

However, findings have shown that being married and having children can be sexist or against gender inequality in education. Two reasons can explain these phenomena. The first is family’s financial difficulties. Financial difficulties can make family choose whether family resources should be allocated to a son or daughter, and most of the time a family would prioritize a son’s education. A study in Germany pointed out girls would be less likely to complete higher education if they had older brothers during times of financial hardship (Jacob, 2011). From the World Economic Forum (2016), poor countries have more women in the workforce, but less in education attainment than men. Second, social norms such as culture, patriarchy, socialization, and religion may compel parents to prioritize son’s education. In some countries, higher education is not found to be useful for daughters since marriage life would begin as early as 13 years old (Obiageli & Paulette, 2015).

Social Class

The findings indicated the education variable presented the gradually declining relationship from the first model to the third model (p < .001*** to p < .01** and to p < 05*). However, the results of the regression on women’s employment pointed out that the dependent variable “women’s employment” has a strong relationship with the independent variables in all models. Therefore, we found an interesting result that there is a different attitude toward women’s education and employment among social classes, indicating upper class people are more likely to have sexist views against women’s employment and education. This means that the gender division of labor and gender stereotypes are strong among the upper class can be a result of the family’s wealth strength motivating men to place less importance on women’s education and employment.

In the global context, over two decades (1995-2015) female workforce participation decreased from 52.4% to 49.6%. The gender gap slightly increased. However, continent wide, female participation in the work force in Northern, Southern, and Western Europe increased by 2.4%, in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific it increased by 0.8%, in Latin America and the Caribbean it increased by 8.1% (ILO, 2016).

Moreover, in a patriarchal society, man is the sole breadwinner while the woman is a full-time housewife doing the unpaid household work such as childcare, cooking, cleaning, and other gender specific roles, permitting society to overlook the significance of women’s education. Man was socialized as a protector, a hero, and an income maker. The economic advantages have forced male breadwinners roles to shift and to acknowledge women’s economic contribution. The rate of dual breadwinner households is increasing. An increasing trend of dual earning couples gives women a place in family’s financial decision making (Winkler, 1988). In return, an earning housewife can be a threat to the male breadwinner role and cause problems (Spitze, 1988). Therefore, the economically independent woman would reduce the male privilege and authority (Hanlon, 2012).

Declining gender stereotypes on sex roles leads to a better share of family resource for a daughter’s education. But it should be noted that the UNESCO reported that “31 million girls of primary school age and 34 million girls of lower secondary school age were not enrolled in school in 2011” (Hutchison, 2014).

Religion

The findings show that being a religious person is likely to influence perception toward sexism and gender stereotypes against woman’s university education (*** p < .001). However, each religious group has different attitudes about women’s education and employment. The global average in education of women is 7.2 years compared to 8.3 years for men. According to the Pew Research Center, on average, Jewish women received 13.4 years of education, Christians received 9.1 years, unaffiliated groups received 8.3 years, Buddhists received 7.4 years, Muslims received 4.2 years, and Hindus received 4.2 years (Pew Research Center, 2016, p. 6).

Similarly, empirical studies across 97 countries conducted by Norton & Tomal (2009) found that Buddhist, Protestant, and nonreligious adherents do not have considerable discrimination against women’s education, whereas Catholicism has a weak effect, and ethno-religions and Muslims have the strongest effects on female education with the lowest percentage of women attaining the education. Cooray & Potrafke (2011) found in their study that culture and religion are the influencing factors that lead to discrimination against women’s education, especially among Muslims. The different degree of sexual freedom in those religious practices leads to a gender gap in education (Becker & WoBmann, 2008) and under-representation of women in other fields. More or less, religion has influence on each individual since some religion has become a cultural part of life.

Conclusion

Most of the findings are not different from what are seen in societies where women’s education and employment are restricted. Sexism is associated with young people, women, religious devotees, married people, and upper class. These factors lay out the restrictions on women’s social mobility and create gender inequality from childhood (Browne, 1998). We do not want to blame the individual’s socialization as the source of influence on the general perception of women’s right to education, but social, economic, cultural, and political factors should be collectively held responsible. More importantly, we also do not try to generalize the whole situation of women’s employment and education by this study.

However, the improvement of women’s education has not been much improved over the last decade as pointed out by UNESCO (UNESCO, 2016, 2018). The report from ILO (2016) indicated that labor participation of women declined only 1.4% over the past decade. This means that urgent tasks have to be carried out to improve the women’s education and employment.

Although our study has not categorized any specific country for analysis, we will look at some specific countries and socio-cultural difference of respondents in future studies to see if there is any difference in the results.

Acknowledgement

The results of the analysis are derived from recoded variables from the World Values Survey’s data. Therefore, I credit all value aspects to the World Value Survey for the data source and my professor for his guidance. I, Vannak DOM take all the errors and failings as my responsibilities alone.

Biographical Notes

Vannak DOM, PhD, is a research assistant at the Institute of Research and Advanced Studies and an adjunct professor at the College of Education, University of Cambodia, CAMBODIA.

He can be reached at The University of Cambodia, Northbridge Road, P.O. Box 917 , Sangkat Toek Thla, Khan Sen Sok, Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia 12000 or by email at <vannak.dom@gmail.com.>

Gihong YI, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Sociology, Hallym University, SOUTH KOREA. .

He can be reached at Hallym University 1 Hallimdaehak-gil, Okcheon-dong, Chuncheon, Gangwon-do, South Korea or by email at gihong@gmail.com

Date of Submission: 2018-02-19

Date of the Review Results: 2018-04-03

Date of the Decision: 2018-08-19