Background

The international community regards the rapid increase in the number of refugees displaced from countries in Africa and the Middle East as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, and human rights violations and the debate of their acceptance in Europe and Asia as a refugee crisis. Both scholars and policymakers have sought to explore and devise solutions and policies that address the issue (Choi, 2016; European Commission, 2015; Park & Suk, 2016; Shin, 2015). In Korea, the acceptance of refugees became a central theme in social discourse in 2018, after the sudden influx of Yemeni refugees to Jeju Island. The refugee debate has rapidly become widespread, spurring increasingly fervent political and social interest and conflict. In a July 2018 Realmeter survey, opposition to refugee acceptance was 53.4% (27.3% strongly oppose refugee acceptance, 26.1% moderately oppose refugee acceptance), up 4.3%p from their June 2018 survey (Realmeter, 2018b[1]; Realmeter, 2018a[2]). The favorable response (37.4%) decreased by 1.6%p between the two surveys (7.7%) strongly support refugee acceptance, 29.7% moderately support refugee acceptance). According to a survey by the Korea Research Institute,[3] 56% of the respondents said they objected to accepting the refugee status of people from Yemen, 24% said they approve of it, and 20% said they don’t (H. W. Chung, 2018). Demonstrations to express negative views on the acceptance of refugees also took place throughout Korea (B. Seo, 2018).

Yet, discussions on the acceptance of refugees in Korea have been limited. Studies on media communication and public opinion are still lacking and need broader and more diverse research. Because of limited opportunities for citizens to gather information through first-hand experience with refugees, information about the wartime plight of refugees and their local cultural background is mostly communicated by the media. Popular forms of digital media technology allow information to be easily shared, constructed, reconstructed, and to influence public opinion on refugee acceptance.

Our study focused on online discourse on YouTube that concerned refugee acceptance. Anyone can freely post their opinions and thoughts, as well as share and communicate with other users by writing comments, making YouTube a space for online media users to express opinions, share ideas, and engage in debate (Ahn & Park, 2007; Jang & Cho, 2014; Jeong & Kim, 2006; E.-M. Kim & Sun, 2006; J.-S. Lee & Lee, 2008; Yang, 2008). The purpose of our study was to understand the trends in public opinion concerning the acceptance of refugees by analyzing the content of refugee-related video commentary on YouTube. We conducted topic modeling to examine central themes, context, and opinions about information acquired through media. As recent research has revealed, Korean media coverage is generally biased against refugee acceptance (Citizens’ Coalition for Democratic Media, 2018). Given this social context, we examined how online users understand and consume video material on refugee acceptance. In so doing, this study aims to understand and evaluate the extent to which public opinion on refugee acceptance demonstrates sophistication, formed in a space where users flexibly and freely engage in communicative behavior.

Literature Review

The Emergence of the Refugee Debate in Korea

A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country to escape war, persecution, violence, or natural disaster. For these individuals, fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group is well-justified (UNHCR, 2019).

South Korea joined the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in December 1992, and its Refugee Act took effect in July 2013, making South Korea the first country in Asia with such a law. In spite of these measures, evaluations show that the country has responded negatively to the problem of refugees (H. Kim, 2018; B. H. Lee, 2018). The resettlement system began to be actively discussed in the 2000s as a form of burden-sharing in the international community and as a permanent solution to the refugee problem. In chairing the UNHCR Executive Committee through 2014, South Korea was expected to implement a refugee policy that would match the country’s economic and international status.

It is rare that the government actually accepts applications for refugee status. However, normative and diplomatic debates on refugees are increasing. The number of refugees entering Korea continues to increase each year. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Justice, 40,470 people applied for refugee status from April 1994 to the end of May 2018. So far, the government has reviewed 20,361 applications for refugee status; 839 of the refugee claimants have been recognized as refugees. This means that only 4.1% of asylum seekers receive refugee status. Humanitarian status was granted to an additional 1,540 foreigners, or 7.6% of the refugee applicants. Several European countries that have taken in refugees have relied on sections of their immigration laws about “humanitarian protection” or “supplementary protection” to guarantee basic medical care, labor permits, and sojourn rights to applicants even when they are not recognized as refugees. South Korea also issues miscellaneous sojourn rights (the G-1 visa) to humanitarian status holders – individuals who must be allowed to remain in South Korea for a long period of time – but unlike in other countries, these individuals do not receive any social support aside from the right to work. Humanitarian status holders are excluded from all kinds of public assistance, including social insurance and basic livelihood allowance. Since they are not issued travel certificates, family members who were unable to enter the country together must continue to live apart. South Korea’s Refugee Act has basically justified the separation of families (Korea Ministry of Justice Immigration and Foreign Policy Headquarters, 2018).

Although the refugee issue calls for a society-wide, in-depth discussion, discussions on the topic within Korea have historically been limited to academics or international diplomacy professionals. Furthermore, this discussion was confined to the concept and policy of migrant workers and refugees (Min, 2003; Y. H. Song, 2018; Yi, 2016), and legal review of refugee protection (H.-J. Kim, 2015; J.-C. Kim, 2014). Even after the refugee issue became important in Europe due to humanitarian crisis in Syria, studies fixated on policies and situations in EU countries (Choi, 2016; Kang, 2016; H. J. Kim & Moon, 2016; H.-K. Kim, 2015; Ko & Ha, 2011; Park & Suk, 2016; Seol, 2013; Shin, 2015).

Since June 2018, coinciding with the influx of Yemeni refugees to Jeju Island, the refugee problem has become a social agenda, spurring the development of more diverse approaches to the situation (H. Kim, 2018). Field research undertaken through direct interviews with refugees aims to better understand how interactions with refugees affect political outcomes (H. Kim, 2018). Other studies reveal the cruelty of human rights violations inflicted on refugee women and suggest policy improvements (H.-J. Song et al., 2018).

Given the low likelihood of the average Korean citizen interacting directly with refugees, the media plays a substantial role in communicating with the public about refugees. However, there is a dearth of research that scrutinizes press coverage on the refugee issue. According to one report, domestic discourse on refugees found in Korean media is restricted to the matter of whether or not to accommodate refugees, who are generally depicted in negative terms. Furthermore, in-depth reporting on the Yemeni Civil War is hard to find, whereas coverage on the so-called refugee side-effects, including public concern about destabilization of employment among Koreans and crimes (or fake news about crimes) involving refugees abound (Citizens’ Coalition for Democratic Media, 2018). As such, accurate information about refugees is needed to form a healthy public opinion. In order to make this possible, we must move beyond simply criticizing negative trends in public opinion polls, emphasizing classical humanitarianism (S. W. Lee, 2018), or lamenting the narrow-mindedness of public discourse on whether or not refugees should be accepted into Korea (Chae, 2018).

Research on the conflicts in public opinion about refugee acceptance and social discourse, particularly from a media communications perspective, is also lacking. Since 2018, several research organizations have published survey results on refugee-related public opinion polls and media reports, but they are generally focused on asking about the pros and cons of accepting refugees and analyzing results through comparison. Therefore, extant research does not offer a nuanced understanding of public opinion on refugee acceptance (Gallup Korea, 2018; Realmeter, 2018b).

In this respect, a 2018 study by Byung-Ha Lee is notable for its analysis of the discursive characteristics of the refugee issue within Korean society following the Korean refugee crisis on Jeju. In recent years, refugee issues have been politicized as a security-oriented discourse among countries hosting refugees, particularly those in Europe. Some politicians and anti-refugee organizations have pointed to the surge in crime rates, the linkage with terrorism, and the burden on welfare systems. B. H. Lee (2018) remarked that it was difficult to say that the refugee issue in Korea had become a security concern, nor had it reached a level to justify extreme measures at the time of writing, but noted that the refugee problem was rapidly changing. He observed that the anti-refugee discourse might combine with the Banda culture discourse, which is based on anti-Islamic sentiment and security fears, and called for countermeasures to address potential politicization. Jef Huysmans (2006) called for attention to everyday life and interaction among immigrants and refugees with the native Korean people as a way to alleviate social fear and threats toward refugees

Public Sphere, Agenda Diffusion Theory, and Social Media

YouTube is situated at the intersection of media production and social networking (Hanson et al., 2011) as a platform on which audiences can easily create media and interact with content. At a basic level, users search for videos and news. In addition, users can reproduce video content or share and disseminate videos to other platforms. The process of content creation and sharing creates a participatory culture, wherein users develop new friendships and communities. This participatory culture fosters social consciousness and social contribution and is characterized by a low barrier to citizen participation and artistic expression (Chau, 2010).

YouTube’s networking capabilities allow for transnational and transcultural communication (J. E. Song & Jang, 2013). More than a billion people globally search for YouTube content in 76 different languages and view billions of videos, accumulating hundreds of millions of hours of daily viewing time (YouTube, 2019). Furthermore, YouTube’s networking capabilities contribute to the formation of international solidarity and public opinion (Pantti, 2015). The comments section catalyzes the formation of public opinion driven by an audience of ordinary citizens, based on citizen experience and popular discourse. Thus, it offers a space for citizens to partake in discussion (Pantti, 2015) and absorb new information (Jenkins, 2006). Furthermore, unlike mainstream media, there are no gatekeepers on YouTube. Rather, the forums that emerge within the space are as diverse as the multiplicity of frames in the video content (Church, 2010; Mosemghvdlishvili & Jansz, 2012).

YouTube also enables dissemination of fresh information and viewpoints on issues such as political conflict (Evans, 2016). The public sphere is “the common world” that “gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other” (Arendt, 1958). The idea of the public sphere of universal enlightenment, participation, and social unity is limited because of the capitalistic nature of mass media production that creates public opinion. The public sphere of social media is the public sphere of difference. It is the new public sphere of various individuals, not the dominant public opinion created by the domination system like mass media. It is a contradictory “'difference of public spheres”’ formed from a small discussion group to a discussion concert, and from blogs and social networks. In the digital convergence era, the contents of the public sphere are “'public societies”’ that have the simultaneous character of standardization and diversification, uniformity and personalization, adaptation and isolation, standardization and mixing, direction and authentication, repetition and variation (M. J. Seo, 2014).

However, the multiple complexities of YouTube also create the potential to adversely affect the direction and depth of YouTube public opinion if it fixates on the negative (Citizens’ Coalition for Democratic Media, 2018). The free conditions within YouTube, combined with the influence of the comments sections and bolstered by confirmation bias, may foreground extreme and unreasonable arguments and violent speech. Such possibilities indicate the need for a mature attitude in the public sphere: specifically, an understanding of the nature of YouTube and an awareness of the influence that a personal level of exchange commands.

Comments Analysis Through a Literature Review of Public Opinion Research

Once formed, public opinion does not dissipate over time but rather enters a cycle in which public opinion influences relevant policy and then reacts to the change in policy (J. Lee, 2014). Without an accurate understanding of public opinion, no social issue can move toward a goal and it is difficult for any policy to be enforced effectively (J. Lee, 2014; Oh, 2005). Thus, analyzing the mechanism through which certain articulations are foregrounded in the media, how certain terms link with other terms, how these articulations are amplified, and the parameters of interpretation these articulations establish enables us to understand how communication takes place within a society.

As demonstrated above, YouTube commentary is a significant research subject in societal communication cycles. The characteristics of comments sections in which users freely express personal opinions to engage in public discussion facilitate researchers’ ability to grasp the social-psychological orientation of the speaker (Lee & Jang, 2009). In a shifting media environment, Internet users influence one another even when they do not directly engage in posting and sharing comments. Users gauge the trends in the comments posted by other users to establish their own position and attitude toward a particular issue (Ahn & Park, 2007; Jang & Cho, 2014; Jeong & Kim, 2006; E.-M. Kim & Sun, 2006; J.-S. Lee & Lee, 2008; Yang, 2008). This means that media users can change their perspectives toward an issue based on their evaluation of the broader public opinion reflected in the comments. Therefore, exposure to a diverse range of perspectives enhances the prospects of informed opinion-making in multiple dimensions. When diverse opinions on conflicting agendas are shared democratically, the comments section serves as a wholesome site of social interaction.

In the case of public opinion on the acceptance of refugees, Korean media reports show a negatively biased view of refugee acceptance (Citizens’ Coalition for Democratic Media, 2018). Identifying how information is understood and consumed by YouTube users through comments left on the platform will help to identify more detailed and flexible aspects of public opinion. As many scholars point out, ordinary users freely expressing personal opinions, thoughts, beliefs, and feelings about news coverage and sharing them with a large number of people has become commonplace (Ahn & Park, 2007; Jeong & Kim, 2006; E.-M. Kim & Sun, 2006; J.-S. Lee & Lee, 2008; Yang, 2008). The provision of in-depth coverage through the introduction of relevant news, nonlinear news consumption using hyperlinks (Ahn & Park, 2007), and interaction among users as well as user-media interaction mediated by comments are the features of online journalism that are important to this study.

Even though conflicts have arisen due to refugees at home and abroad, there is a need to explore alternatives to news coverage that self-limits to emphasis on the presence of conflict itself, encouraging biased perspectives. Online platforms add an interpersonal communication element to the traditional mass communication form of news articles (Yang, 2008). Extremely personal and unpolished opinions are widely circulated and consumed alongside news articles, with almost no control or censorship — and unfiltered information tends to be biased. Existing research indicates that news consumers who access comments that diverge from the tone of the accompanying news tend to adopt the opinion of other online users based on the comments (Lange, 2019). In other words, users who are exposed to comments are more likely to be affected by public opinion, rather than forming their own opinions uninfluenced by others. Yet, as demonstrated in a recent German study, a level of direct experience can offer communication-based solutions to social conflicts involving refugees. Therefore, identifying the characteristics of comments that stem from individual and personal experiences may be an essential first step in finding solutions for the social integration of refugees (Lange, 2019).

Research Methods

Research Question

To analyze the characteristics of the refugee-related comments we developed the research questions as follows.

What are the characteristics of videos related to refugee acceptance?

-

Which types of refugee-related videos are primarily discussed?

-

What are the characteristics of the vocabulary in the videos?

What are the characteristics of refugee-related public opinion comments in the video comments?

-

What are the characteristics of the vocabulary in the comments?

-

What are the main topics of the messages that appear in comments?

-

In what context is the vocabulary of the comments used?

Research Procedures

In this study, data collection, pre-processing and analysis were conducted in respective order. We crawled uploaded YouTube videos and comments for six months starting in June of 2018. We chose this timing because the number of off-line discussions in which refugee cases have become issues in Korea had recently increased.

Big data research is not only large-scale data analysis but an inductive and interpretive form of analysis to better understand a phenomenon and draw a more comprehensive interpretation and discussion. The researchers continued deliberation and discussion while going through the research process.

Research Methodology

Text mining. Text mining is a big data analysis method used to extract meaningful information and assess the relationship of texts by analyzing various types of informal data such as online comments and Twitter messages (Korea Database Agency, 2016). It allows researchers to collect a large amount of text data and yields subject categories without having to define a topic a priori (Karrer & Newman, 2011) and is thus useful when categorizing content. Text mining consists of data collection, morphological analysis, semantic transformation and extraction, and keyword and topic analysis. In this study, data collection was implemented in a bottom-up collection method in which the data on the subject were first collected, then categorized, and the keywords corresponding to each category determined. Subsequently, data preprocessing was performed to remove unnecessary information and format the irregular data of the text. Morphological analysis was then performed after eliminating characters such as punctuation, symbols, and spaces. Morphological analysis is a process of separating the sentence into a meaningful minimum unit, or morpheme, and verifying the part of speech. In this study, we used the KoNLP analyzer and analyzed the morpheme, excluding nouns. Additionally, words that were unnecessary for analysis among nouns were treated as an abbreviation so that future topic modeling analysis could proceed more smoothly. Finally, we used Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) for the text data to determine the importance of specific words in the document.

Analysis of association rules. Association rule analysis is a technique of data mining, which finds a reasonable rule of fit between objects in a large set of data. It is also called affinity analysis or shopping cart analysis. It refers to the task of extracting interrelationships, such as “when an event occurs, another event occurs,” and first finds a frequent item set. Support and confidence are used as evaluation criteria of extracted association rules. Support is the ability to identify trends in transactions by indicating which transactions contain both X and Y in the entire transaction.

Reliability is the ratio of item Y included in a transaction that contains item X. If the degree of enhancement is equal to 1, then X and Y are independent of each other, if less than 1 a negative correlation, if more than 1 and has a positive correlation. If two items are adopted at the same time, they are independent. If the improvement value is 1, they are completely independent. The value of the enhancement must be greater than 1 (S.-Y. Chung & Kwon, 2008). The rules that satisfy both the minimum support and the minimum reliability are called strong rules. In this study, the support and reliability values are presented together with the related words.

Topic modeling. Topic modeling is a method of text mining as a statistical reasoning model used to find the subject of a document (Blei et al., 2003). Research is focused on analyzing and exploring trends according to the characteristics of data. The number of texts such as newspaper articles and unrefined social media is rapidly increasing, and research is being conducted to understand the opinions of users in the online ecosystem.

The topic modeling technique used in this study is latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). LDA is a topic modeling technique proposed by Blei et al. (2003), which refers to a probabilistic model in which subjects exist in a given text. LDA has several advantages, including the simplicity of the algorithm itself, the usefulness of data reduction, and semantically consistent subject production (Mimno et al., 2008).

LDA topic modeling is essentially an analysis based on the subject distribution of a text group and the probability of occurrence of thematic words. Therefore, the researcher sets the number of subjects that the text potentially has and the number of words representing the subject. The number of topics is determined by considering both the interpretability of the topic and the perplexity value by the estimation method. In this study, eight topics were set as the number of potential topics. To ensure both efficiency and accuracy, Gibbs sampling, which sets the appropriate number of iterations, is set to a repetition frequency of 1000 (Hornik & Grün, 2011). In this way, the topic model is generated efficiently, and the accuracy of the model is secured.

Results

Analysis of the Characteristics of the Videos

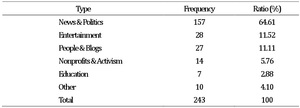

We first analyzed the frequency and type of videos related to refugee acceptance. The video type can be indicated as a genre on YouTube, which is specified on upload. The results of our video type analysis, shown in Table 1, indicate that videos related to refugee acceptance are most frequently handled in News & Politics (64.61%). Entertainment and People & Blogs followed in the ranking. Other areas included types of games, travel, cars, and movies.

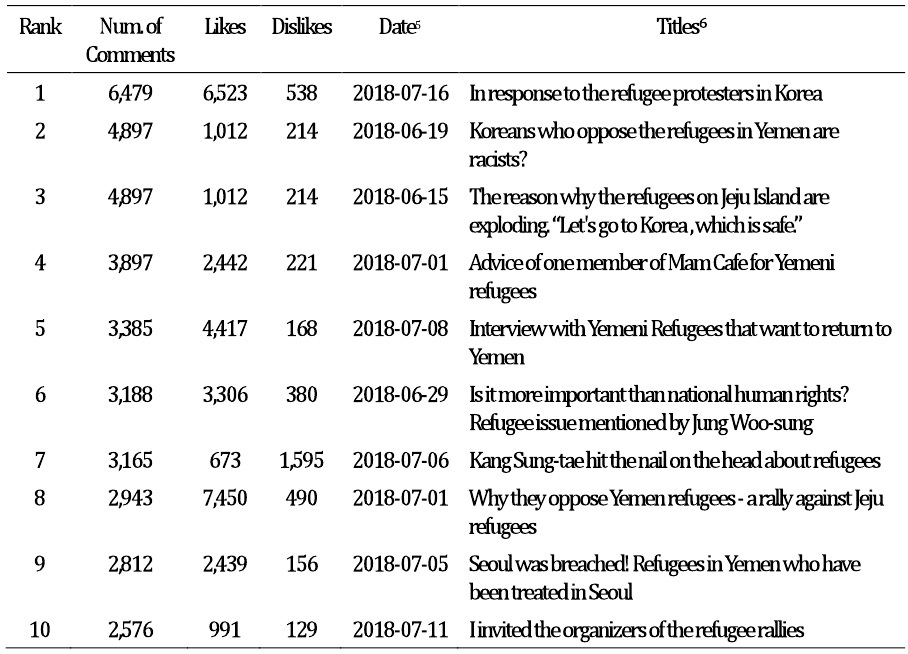

Among the videos included in our study, the ten with the greatest number of comments are listed below (Table 2).

Word Frequency Analysis

Through our research, we compiled a list of the top thirty words most frequently appearing in refugee-related videos. Within both the video title and the video text, “refugee” (209/204), “Jeju” (79/185), and “acceptance” (48/133) occurred with the highest frequency. In the video title, the words such as “Rally,” “Problem,” “Acknowledge,” “We,” “Fake,” “Permit,” “Petition,” “Humanitarian,” and “Muslim” also appeared frequently. In the video content, the words such as “Tip-off,” “The opposite,” “Human,” “Screening,” and “Entry” appeared frequently.

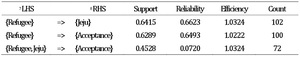

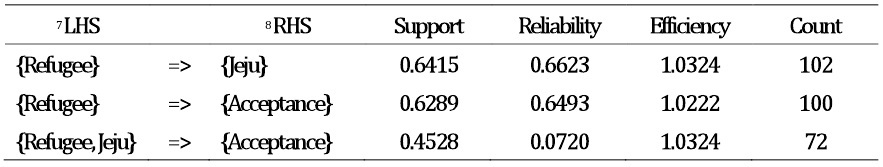

Analysis of Association Rules between Words in Video

We conducted an analysis of association rules to examine the meanings of the words used in the videos. A total of 47 rules were found at a support level of 0.1 and a reliability level of 0.77. As the results in Table 4 demonstrate, ‘Jeju’ and ‘acceptance’ appeared as the words most frequently related to ‘refugees.’ When ‘refugees’ were used together with ‘Jeju,’ there was a relationship with ‘acceptance.’ The results of the association analysis showed that refugee videos mainly dealt with the pros and cons of refugee acceptance on Jeju, reinforcing the findings of our earlier word frequency analysis.

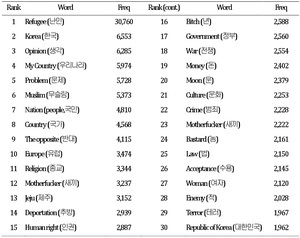

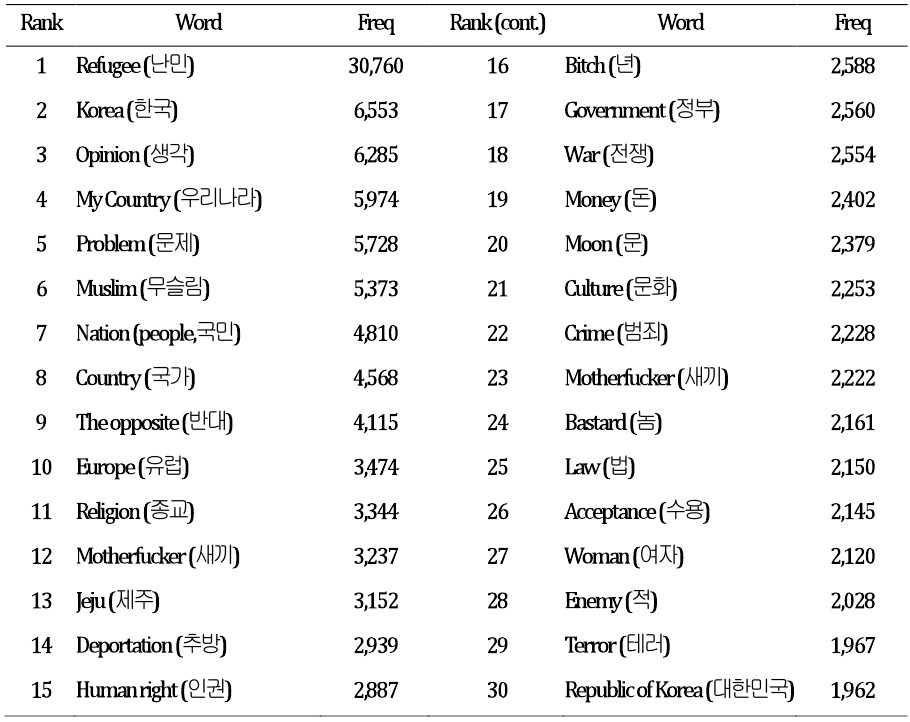

Word Frequency Analysis on Comments

To address our second research question, “What are the characteristics of refugeerelated public opinion in the video comments?”, we conducted text mining of comments to derive the frequency of common words, as shown in Table 5. Word frequency analysis of the comments section indicated that the words “refugee” (30,760), “Korea” (6,553), “opinion” (6,285), “my country” (5,974), and “problem” (5,728) appeared most frequently.

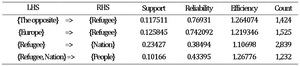

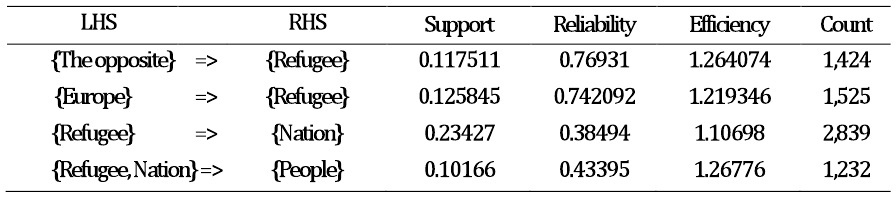

Analysis of Association Rules

Following our analysis of words that appear most frequently, we conducted an association rules analysis to examine the meanings of words used in the text of the videos. A total of 74 rules were found at a support level of 0.1 and a reliability level of 0.77, shown in Table 6.

Unlike the analysis of video content, “the opposite” and “Europe” appeared as the two most frequent words following the term “refugees.” The word that showed the highest degree of association with “refugees” was “country.” When “country” and “refugee” were used together, it was in relation to the word “people.” Furthermore, when complete sentences were examined, we often encountered a line of reasoning which presented the issue of refugee acceptance as a problem for “our country” and a problem for “our people,” and that opposing refugee acceptance is only a natural expression as a citizen of Korea.

Topic Modeling Analysis of User Comments

To further analyze the attitudes toward refugee acceptance in our earlier results, we conducted topic modeling analysis, tracing the keywords of each topic from the original text. Table 4 summarizes the results and keywords derived from appropriate topics through topic modeling. After extracting the 10 final topics, we integrated contextually similar topics. The findings enumerated the different forms of hate toward the refugees shown in the discourse, or different perceptions of hate projected onto the refugee issue.

First, hatred toward a region (“Regionalism”) appeared within the debate on refugee issues. Some of the main words that make up this topic are “Chosun,” “Jeolla[4] Province,” “Gwangju,” “Chun Doo Hwan,” and “Park Chung Hee.” Comments that did not have any direct relevance to refugee acceptance frequently occurred, such as “How can a country that has undergone the Gwangju People’s Uprising[5] accept refugees?” (Jaemin Choi, 7 months ago), “I do not care if they [refugees] are to go to Jeolla-do,” and “Do it like Jeolla-do” (Minsu Kim, 7 months ago). Other comments brought up the responsibility of Jeolla-do or criticized news coverage for misleading the public as it did for the Gwangju protest.

In the case of “Political Criticism,” those politicians who favored refugee acceptance were referred to as “advocates.” Users expressed a desire to ostracize those politicians or to hold accountable certain conservative or progressive parties. The “Protecting the People” topic, which consists of words such as “people,” “country,” “Islam,” and “Korea,” conveyed an extremist and closed national protectionist tendency that dichotomously divides the Korean people and refugees. In the comments, people only recognized refugees as terrorists and criminals. They also described refugees as “perpetrators of crime,” citing arrests and terrorism, mentioning the attempted hijacking of a Russian aircraft.[6] Another topic, “opposing actions” dealt with measures such as petitions, signatures, and voting.

In the case of the topic involving words such as “Disaster,” “God,” “Unity,” “Bible,” “Jesus,” “Communism,” and “Destruction,” religious hatred or religious exclusion figured heavily. Finally, the topic of “Hatred for immigrants” consisted of the terms “Islam,” “War,” “Temple,” “Breeding power,” “Rear,” and “Expansion.”

Conclusions

In this study, we examined how the current debate about refugees has been triggered and sustained by online media. For our analysis, we conducted text mining to collect and analyze videos related to refugee acceptance in Korea and the comments on these videos. We employed topic modeling analysis to collect words from a set of documents, to extrapolate groups of words associated with specific subjects relating to the refugee situation, and to infer the topic of the video.

We found that the videos concerning refugee acceptance were mainly dealt with in the genre of news and politics, and that these videos tended to generate words such as refugees, Jeju, pros and cons, and acceptance. In the comments sections, Jeju and acceptance appeared frequently as words associated with refugees, while refugees and Jeju were associated with acceptance. These findings indicated that the media tends to focus on the pros and cons of refugee acceptance, while public opinion also tends to fixate on the issue of whether or not to accept refugees, in the case of the Yemeni refugees of Jeju Island. We employed topic modeling to examine the context of each word, and derived associated topics such as regionalism, immigrant hate, and religion. The discourse of refugee acceptance was scattered across various forms of hate toward refugees.

Through our research, we compiled a list of the top thirty words most frequently appearing in refugee-related videos. Within both video title and video text, “refugee,” “Jeju,” and “acceptance” occurred with the highest frequency. In the video title, the words such as “Rally,” “Problem,” “Acknowledge,” “We,” “Fake,” “Permit,” “Petition,” “Humanitarian,” and “Muslim” appeared frequently. In the video content, the words such as “Tip-off,” “The opposite,” “Human,” “Screening,” and “Entry” appeared frequently. Overall, public opinion on refugee acceptance showed that the intersection between extreme discussions and nuanced opinions was insubstantial, that evidence supporting the arguments were not visible, and that violent forms of language and hate speech comprised the majority of the texts of these videos.

These features of online platforms shown in YouTube comments sections undesirably limit the participation of diverse perspectives that could reduce ignorance and instead allow blind hatred to proliferate. Social media, which should be the public sphere of differences in the new media era, is meaningful for the public opinion field.

In particular, by grouping refugees into a collectively oversimplified dichotomy of national or religious background, the extent and depth of public discourse about refugee acceptance become constricted. Therefore, it is imperative that we diversify and rationalize public discussions. In other words, we must adopt a new approach to address the refugee issue in a way that transcends a securitization approach (Buzan et al., 1998), to be negotiated across a diverse range of political and everyday cultural realms. To this end, the media, the government, and citizens should be alert to the detrimental effects of hate and boundary-marking as perpetuated in online comments sections. Each entity faces the challenge of entering the public sphere with a mature attitude, seeking to understand and empathize with different positions and perspectives.

Limitations

The purposive sampling of keyword selection process for data collection, driven by the intent of our research, was one limitation of our study. Furthermore, the data selection period was limited to six months in consideration of the abundance of refugee discussions. The gap between the period in which the research was being completed and the time frame of our study may have somewhat affected the timeliness of our results.

Conclusions

In this study, we examined how the current debate about refugees has been triggered and sustained by online media. For our analysis, we conducted text mining to collect and analyze videos related to refugee acceptance in Korea and the comments on these videos. We employed topic modeling analysis to collect words from a set of documents, to extrapolate groups of words associated with specific subjects relating to the refugee situation, and to infer the topic of the video.

We found that the videos concerning refugee acceptance were mainly dealt with in the genre of news and politics, and that these videos tended to generate words such as refugees, Jeju, pros and cons, and acceptance. In the comments sections, Jeju and acceptance appeared frequently as words associated with refugees, while refugees and Jeju were associated with acceptance. These findings indicated that the media tends to focus on the pros and cons of refugee acceptance, while public opinion also tends to fixate on the issue of whether or not to accept refugees, in the case of the Yemeni refugees of Jeju Island. We employed topic modeling to examine the context of each word, and derived associated topics such as regionalism, immigrant hate, and religion. The discourse of refugee acceptance was scattered across various forms of hate toward refugees.

Through our research, we compiled a list of the top thirty words most frequently appearing in refugee-related videos. Within both video title and video text, “refugee,” “Jeju,” and “acceptance” occurred with the highest frequency. In the video title, the words such as “Rally,” “Problem,” “Acknowledge,” “We,” “Fake,” “Permit,” “Petition,” “Humanitarian,” and “Muslim” appeared frequently. In the video content, the words such as “Tip-off,” “The opposite,” “Human,” “Screening,” and “Entry” appeared frequently. Overall, public opinion on refugee acceptance showed that the intersection between extreme discussions and nuanced opinions was insubstantial, that evidence supporting the arguments were not visible, and that violent forms of language and hate speech comprised the majority of the texts of these videos.

These features of online platforms shown in YouTube comments sections undesirably limit the participation of diverse perspectives that could reduce ignorance and instead allow blind hatred to proliferate. Social media, which should be the public sphere of differences in the new media era, is meaningful for the public opinion field.

In particular, by grouping refugees into a collectively oversimplified dichotomy of national or religious background, the extent and depth of public discourse about refugee acceptance become constricted. Therefore, it is imperative that we diversify and rationalize public discussions. In other words, we must adopt a new approach to address the refugee issue in a way that transcends a securitization approach (Buzan et al., 1998), to be negotiated across a diverse range of political and everyday cultural realms. To this end, the media, the government, and citizens should be alert to the detrimental effects of hate and boundary-marking as perpetuated in online comments sections. Each entity faces the challenge of entering the public sphere with a mature attitude, seeking to understand and empathize with different positions and perspectives.

Limitations

The purposive sampling of keyword selection process for data collection, driven by the intent of our research, was one limitation of our study. Furthermore, the data selection period was limited to six months in consideration of the abundance of refugee discussions. The gap between the period in which the research was being completed and the time frame of our study may have somewhat affected the timeliness of our results.

Appendix: Original, Untranslated Data

Biographical Notes

Sook Choi is an academic research professor in the Media Communication Research Institute at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. She received her PhD in Media Communication from HUFS.

She can be reached at Media Communication Research Institute at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, 107, Imun-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 02450, Korea or by e-mail at sookchoi@hotmail.com

Si Yeon Jang is a doctoral candidate at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, working as a lab researcher at Media and Communications Research Institute.

Correspondence

All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Si Yeon Jang at Media Communication Research Institute at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, 107, Imun-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 02450, Korea or by e-mail at siyeonjang@gmail.com.

Date of submission: 2019-05-09

Date of the review results: 2019-07-24

Date of the decision: 2019-07-31

Sampling Method: Proportional allocation by region, gender, age, education, and occupation. Sample size: 500 people. Sampling error: 4.4% at the 95% confidence level. (2018 Jun 20).

Sampling Method: Proportional allocation by region, gender, age, education, and occupation. Sample size: 500 people. Sampling error: 4.4% at the 95% confidence level. (2018 Jul 4).

Sampling Method: Proportional allocation by region, gender, age, education, and occupation. Sample size: 1000 people. Sampling error: 3.1% at the 95% confidence level.

Jeolla-do is the name of the region where the Gwangju People’s Uprising took place. This word is used as a regional derogatory word in South Korea.

The Gwangju People’s Uprising was a pro-democracy demonstration in 1980 leading to the deaths of 200 people. For more information see Korean Resource Center (n.d.).

For more information about this incident, see Quackenbush (2019).