The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been profound, marked by widespread political polarization. This polarization has led to significant divergence in public perceptions of COVID-19 severity and responses to infection prevention and control measures along partisan and ideological lines. Such divergence often stemmed from varying responses of political leaders to the pandemic. Some leaders prioritized public health measures such as wearing face masks and practicing social distancing, while others downplayed the virus’s severity and focused on reopening the economy (Gadarian et al., 2021; Green et al., 2020; Merkley et al., 2020). Notably, voters often followed these elite cues, with discernible consequences for health outcomes.

Elite divergence in attitudes toward COVID-19 was also reflected in media coverage. In the United States, media outlets aligned with Democrat elites emphasized healthcare professionals’ views, while conservative outlets tended to downplay the pandemic’s severity, aligning with Republican elite narratives (Allcott et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Media divergence had a tangible effect on public perceptions; studies in the United States indicated that individuals relying on conservative media were less likely to believe in COVID-19 risks and comply with prevention guidelines (Clinton et al., 2021; Gollwitzer et al., 2020; Simonov et al., 2020), contributing to higher death rates among those perceiving the disease as less serious (Chen & Karim, 2022; Sehgal et al., 2022). This political polarization extended to European and Latin American countries, resulting in varying levels of compliance with public health measures (Aruguete et al., 2021; Calvo & Ventura, 2021; Vlandas & Klymak, 2021) and higher death rates in polarized regions (Charron et al., 2023).

Despite extensive research in this area, there remains a notable gap in understanding how news coverage of COVID-19 varies based on the political orientation of media outlets, particularly in countries such as South Korea, where the pandemic’s impact resulted in relatively lower death rates among countries severely impacted by COVID-19. In addition to effective government measures, such as widespread testing, rigorous contact tracing, and the extensive use of technology, South Korea’s successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to several cultural and societal factors. The country’s collectivist culture, which emphasizes group harmony and the community’s well-being over individual interests, was instrumental in ensuring widespread public compliance with government directives (S. Song & Choi, 2023). This cultural orientation, combined with a strong technological infrastructure and a well-prepared healthcare system (S. M. Lee & Lee, 2020; Moradi & Vaezi, 2020), facilitated the effective implementation of preventive and control measures (J. Kang, 2020).

However, South Korea’s media landscape is characterized by pronounced partisanship (Han, 2018; J.-H. Lee & Lee, 2016; Y. Park & Kim, 2016). In particular, the Chosun Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo, and DongA Ilbo newspapers generally support conservative views, while Hankyoreh and Kyunghyang Shinmun are progressive (J. Lee, 2022; Moon, 2020; J.-H. Park, 2020). Previous work suggests that South Korean newspapers often reveal biases linked to their ideologies (E. Lee, 2008; Rhee & Choi, 2005), making South Korea an ideal case to investigate partisan bias in COVID-19 coverage, despite the country’s successful response to the pandemic.

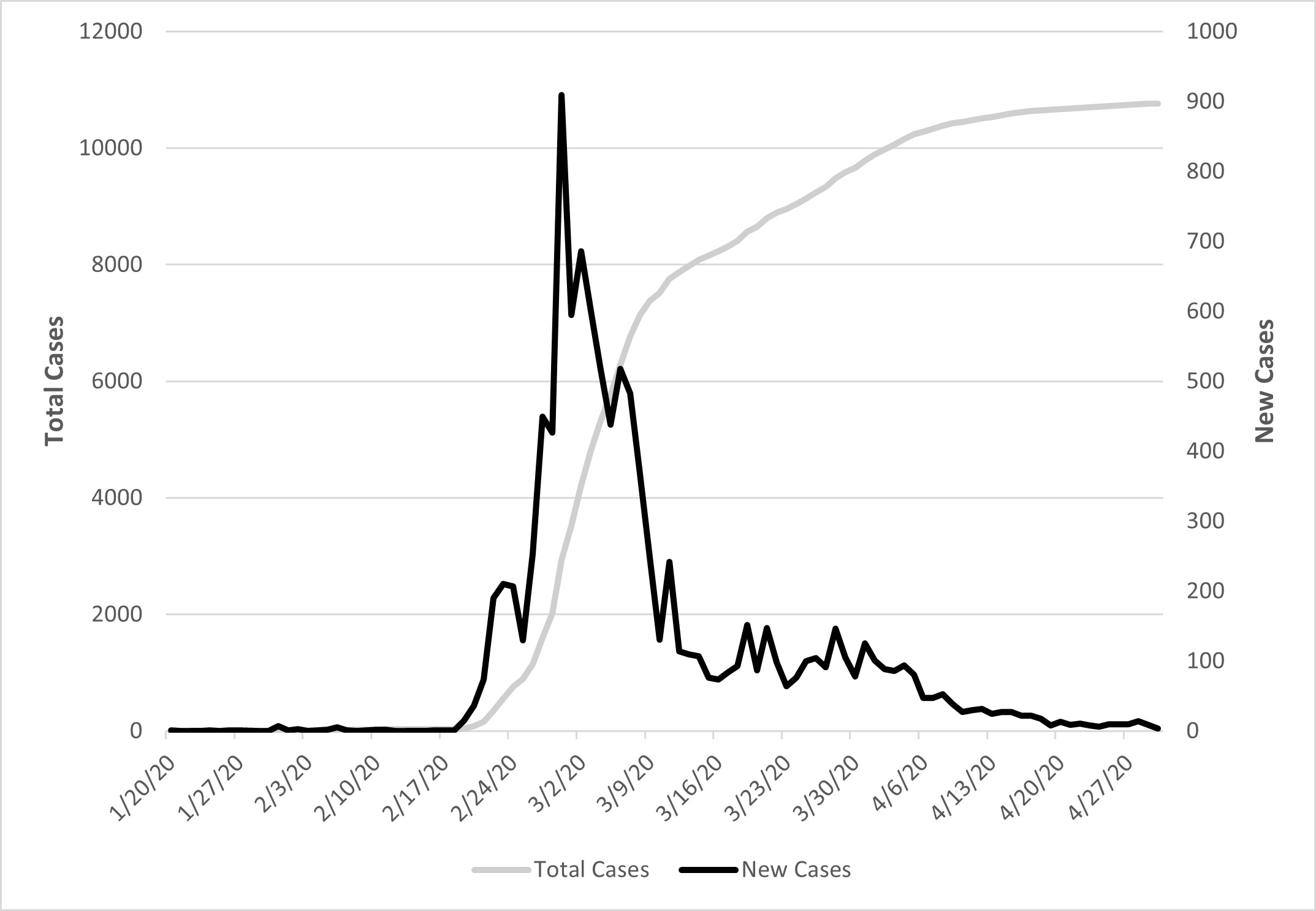

In the early months of 2020, South Korea witnessed a significant outbreak of COVID-19, prompting the progressive government to implement the “K-Quarantine” program, which resulted in a sharp decline in coronavirus cases (see Appendix A). However, while globally recognized as a successful response, the government faced criticism for other aspects of its crisis management, including a shortage of face masks during the critical early stages of the pandemic. This combination of successful and unsuccessful policy outcomes during these initial phases of the pandemic likely gave media outlets the freedom to emphasize facts that make their side look good and the other side look bad, even while they agreed about the seriousness of the pandemic.

This study addresses two research questions: (1) How do conservative and progressive media outlets in South Korea converge and diverge in their framing of the COVID-19 crisis? and (2) To what extent do partisan outlets emphasize responsibility for government responses versus the general aspects of the pandemic? By explicitly focusing on responsibility attribution alongside broader coverage, this study refines existing theories of crisis framing in a polarized media environment. We investigate these questions through automated content analysis of two leading newspapers, DongA Ilbo (conservative) and Hankyoreh (progressive), comparing tone and topics in their early coverage of the pandemic. In the South Korean context, progressive outlets were generally aligned with the progressive Moon Jae-in administration during the pandemic, while conservative outlets often represented opposition perspectives. For clarity, we consistently use the terms “progressive” and “conservative” to describe the media outlets under analysis, rather than “pro-government” or “anti-government.”

Our findings highlight that both conservative and progressive news outlets converged on the severity of COVID-19, covered the disease in largely similar ways, and both sides underscored the importance of implementing effective prevention and control measures for public health. This convergence contrasts with the politicized divergence on the seriousness of the disease itself that emerged in the United States and many other countries, where media coverage of COVID-19 has been studied. However, despite this convergence, they diverged in their assessments of government responses, mirroring elite narratives. Progressive media emphasized successful aspects of COVID-19 policies, while conservative media placed greater emphasis on perceived shortcomings. Moreover, each emphasized solutions to the crisis that aligned with those being advocated by party elites. The analysis of the South Korean case sheds light on the partisan media’s sophistication in selectively politicizing certain aspects of pandemic coverage, aligning precisely with elite narratives.

The implications of this research extend beyond the immediate context of South Korea. Understanding how media coverage is influenced by partisan biases during a public health crisis can offer critical insights for other countries facing similar challenges. This research contributes to the broader discourse on media partisanship by highlighting how ideological alignments can shape the framing of crucial issues during a crisis, thereby affecting public opinion and, potentially, policy outcomes. The findings of this study could have important implications for policymakers, media professionals, and scholars alike by providing a deeper understanding of the role that partisan media may play in crisis communication.

The role of the media in shaping public perceptions, especially during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, has garnered significant scholarly attention. Media outlets, as crucial conduits of information, wield substantial influence in molding public attitudes (De Vreese et al., 2011; Price et al., 1997). Citizens often turn to mass media, particularly in navigating new or complex issues, to understand the stance of their preferred party elites and form opinions based on news cues (Zaller, 1992). This influence can be heightened in public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, where the issue is unfamiliar and directly tied to public safety (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976; Ziporyn, 1988).

Media bias, encompassing systematic favoritism, prejudice, or unfair representation in news reporting, is particularly evident in partisan media bias. This form of bias reflects the political or ideological slant of news coverage, where certain political actors, policies, events, or topics are favored, criticized, emphasized, or ignored depending on the outlet’s leanings. Partisan media bias manifests in how competing media outlets cover the same political stories within the same timeframe, influencing their narratives through selective fact presentation, framing, and tone (Shultziner & Stukalin, 2021). Such bias can involve the use of positive or negative language, the balance between optimistic and pessimistic facts, and the inclusion of particular opinions, all of which contribute to shaping public perceptions (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2010; Groseclose & Milyo, 2005). Research consistently highlights disparities in political coverage across partisan outlets, reinforcing their ideological positions (Chan & Lee, 2014). By focusing on selective events or issues, partisan media tend to create “a unified liberal or conservative perspective on the news” (Levendusky, 2013, p. 612).

These dynamics can be understood through the lens of framing theory. Framing refers to the process of emphasizing certain aspects of an issue to promote a particular interpretation (Chong & Druckman, 2007). Common frames include attribution of responsibility, conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality (An & Gower, 2009; Semetko & Valkenburg, 2000). In crisis contexts, responsibility framing is predominant as it assigns causation or proposes solutions by attributing responsibility to governments, specific individuals, or groups. By contrast, conflict frames center around disputes and disagreements regarding crisis strategies, problem severity, potential fatalities, and solutions. These frames provide opportunities for bias, as partisan media can either emphasize or downplay government responsibility or conflict depending on their political inclinations. For the purposes of this study, we conceptualize “partisan media bias” as the systematic and selective emphasis of issues that align with political elites’ narratives, rather than necessarily inaccurate or distorted coverage. This conceptualization allows us to observe bias even when outlets report factually accurate information.

Recent studies have examined media framing of the COVID-19 pandemic across various countries. For instance, a comprehensive global analysis identified common themes and regional variations in how media outlets across 20 countries emphasized different aspects of the pandemic, such as health, economic impact, and governmental responses (Ng et al., 2021). In South Korea, research highlighted the media’s positive framing of the country’s pandemic responses compared to other nations, noting that this international comparative framing significantly boosted public support for the government and contributed to the ruling party’s success in the 2020 legislative election (Jo & Chang, 2020). However, while these studies provide valuable insights into the impact of national contexts on pandemic narratives and the political implications of COVID-19 coverage, they overlook the nuanced dynamics within politically polarized countries like South Korea or lack a detailed analysis of how specific media outlets with differing political orientations framed the government’s response.

Research on media bias in South Korea aligns with established patterns identified in the existing literature. During presidential elections, media outlets tend to report favorable or unfavorable poll numbers for candidates they support or oppose (B. K. Song, 2020) and focus more on political rumors about ideologically incongruent candidates, with these rumors being framed in a way that highlights their weaknesses (H. Lee et al., 2022). Bias also influences the coverage of crises. During the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) crisis, outlets differed in their application of the attribution of responsibility frame (S. Lee & Paik, 2017). Anti-government media attributed more responsibility for the causation of the crisis to the government, while pro-government media emphasized individuals’ actions in spreading the disease. Recent studies extend this perspective by showing how partisan biases influenced both public evaluations of government performance and economic conditions during the pandemic (H. Lee, 2025b, 2025a). Together, these findings demonstrate that partisan framing shapes not only health-related attitudes but also broader domains of public opinion.

Given the distinctive circumstances surrounding the early phases of the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea, where political disputes predominantly centered on the government’s response, this study anticipates uncovering divergent media patterns based on the outlet’s political orientation, particularly within the responsibility frame. Unlike other countries where partisan bias in crisis media coverage was manifested within the conflict frame, often revolving around the severity of COVID-19 or its potential fatalities, South Korean media coverage may have focused on attributing responsibility for the successes or shortcomings of solutions to the crisis, depending on the outlet’s ideological closeness to the government. Hankyoreh, which shared a progressive orientation with the then-government, is predicted to emphasize the successful aspects of government policies. Conversely, the conservative DongA Ilbo, aligned with the then-leading opposition party, is expected to highlight perceived failures in government policies, such as the mask shortage crisis.

Data and Methods

This study examines media coverage during the initial three months of the COVID-19 pandemic, from January 20 (the date of the first reported case) to April 15, 2020 (the day of the 21st legislative elections). This timeframe was selected as it coincides with the legislative election period, a critical time for understanding how crisis media coverage might influence public opinion during significant political events, where incentives for partisan-based discourse should be highest. Moreover, this period represents South Korea’s most intense phase of the pandemic, with a peak in confirmed cases followed by the implementation of key government policies that were contested. Afterward, South Korea entered a phase of smaller-scale community infections, stabilizing the COVID-19 situation with fewer contentious points (Government of the Republic of Korea, 2020). By focusing on the early stages, this study provides a detailed examination of a critical response period and an essential snapshot of how media outlets initially framed the pandemic and the government’s actions at a time of heightened stakes and uncertainty.

The analysis is grounded in a systematic collection of articles from two major South Korean newspapers, DongA Ilbo and Hankyoreh, which represent conservative and progressive viewpoints, respectively. Articles featuring the keyword “COVID-19,” published between January 21 and April 14, 2020, were collected. The dataset comprises a total of 11,271 articles, with 141 editorials and 6,605 general articles from DongA Ilbo, and 110 editorials and 4,415 general articles from Hankyoreh.

The media analysis proceeds in two steps (see Appendix B for details). First, the study examines whether outlets differed in their tone. Employing a Korean sentiment lexicon, the ratios of positive and negative articles between DongA Ilbo and Hankyoreh were compared, as well as within each media outlet, distinguishing between editorials and general articles. This analysis aims to uncover potential biases in how each newspaper portrayed the pandemic. Next, the specific topics emphasized by the newspapers were analyzed. While both newspapers used similar words (see Appendix C for word frequency analysis), the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model developed by Blei et al. (2003) was employed to identify the dominant topics in each newspaper’s coverage. LDA is an unsupervised machine-learning technique that infers topics from text documents by clustering words with similar meanings based on contextual clues (Steyvers & Griffiths, 2007; Syed & Weber, 2018). The LDA model was built with the number of topics (k) set at 17 for DongA Ilbo and 18 for Hankyoreh, determined through hyperparameter tuning. By comparing the topics covered by these politically opposed newspapers, the analysis explores how pandemic news coverage diverged based on the media’s partisan bias. These methods allow us to see if the newspapers diverged in their tone, how papers framed responsibility for outcomes, and how they emphasized conflict. In this study, responsibility frames were operationalized as topics attributing success or failure to government actions (e.g., mask shortages, relief funds, presidential performance), while conflict frames would have been evident in overt disputes over the severity of COVID-19, which were largely absent in the South Korean case.

While sentiment analysis only captures tone, it provides a complementary perspective on partisan evaluations that enriches the topic modeling analysis. LDA, as an exploratory method, offers a transparent way to identify systematic patterns of convergence and divergence in coverage. Although alternative approaches such as Structural Topic Modeling (STM) could incorporate outlet ideology as a covariate, our choice of LDA provides an appropriate first step in mapping differences in coverage across partisan lines. Future research may employ STM or supervised classification to extend these findings.

Data Analysis and Findings

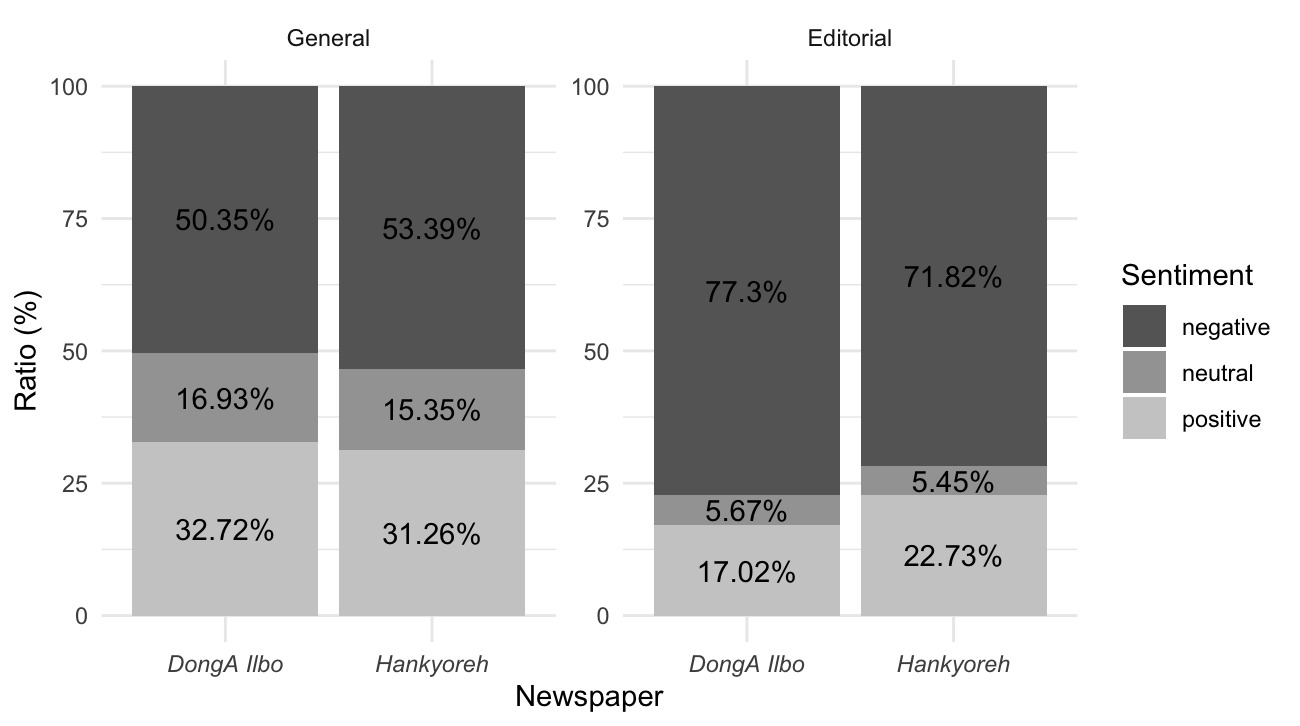

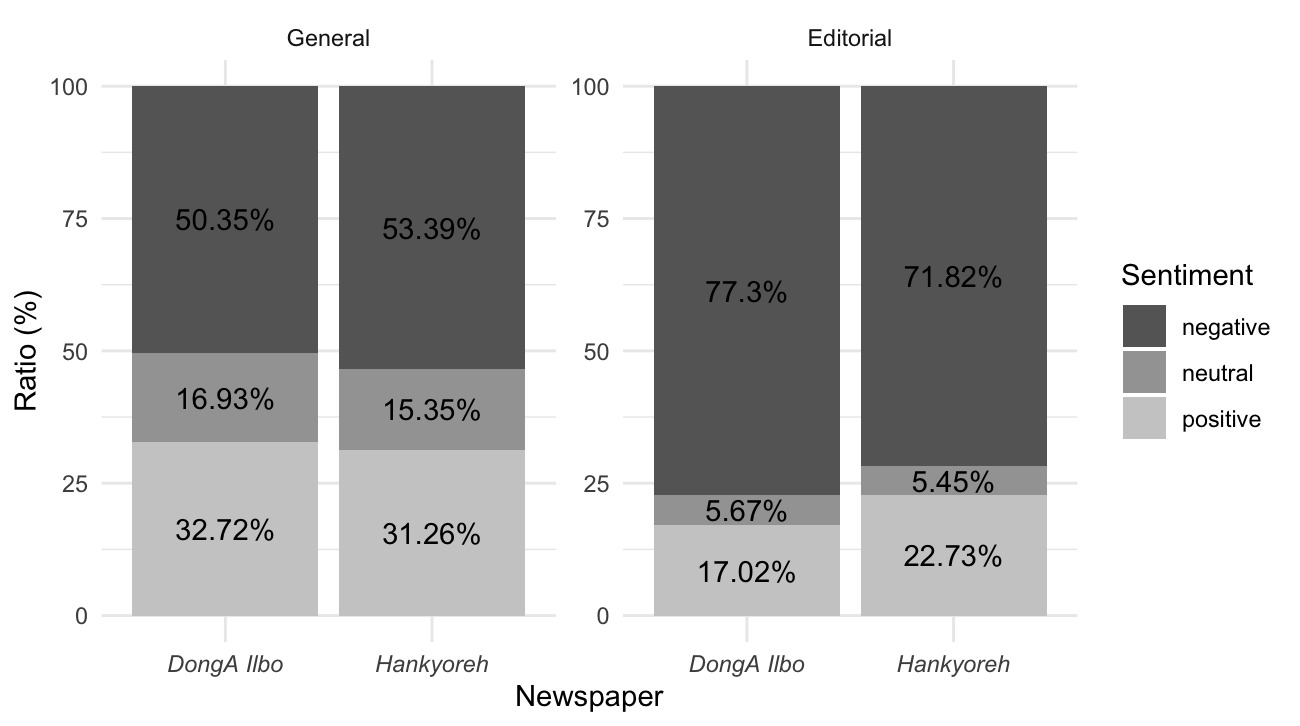

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of sentiment analyses for DongA Ilbo and Hankyoreh’s editorials and general articles on the COVID-19 pandemic. As one would expect during a crisis of this magnitude, the bulk of the coverage carried a negative tone. However, the sentiment analysis, particularly in editorials, uncovers a significant divergence in pandemic coverage between progressive and conservative media outlets. The progressive Hankyoreh’s editorials were over 5% more likely to use positive language than those of the conservative DongA Ilbo. General news coverage also varied in tone, but the differences between the two outlets were smaller, with positive and negative article ratios differing by around 2%. This divergence demonstrates the influence of partisanship on media coverage, especially in the editorial sections of South Korea’s major dailies.

Figure 1.Comparison of Sentiment Analysis in General and Editorial Articles

Note. Ratios represent the proportion of positive, neutral, and negative articles in each newspaper. DongA Ilbo is a conservative outlet, whereas Hankyoreh is a progressive one.

Table 1 moves beyond tone to see if the papers emphasized different aspects of the crisis. The LDA model looks at the major themes emphasized in the coverage (see Appendix D for details). There are many similarities between the papers. They extensively covered the widespread community transmissions originating from an outbreak in a specific region of the country within a particular religious group (“The Shincheonji Crisis” and “Community Transmission”). Moreover, both outlets devoted significant attention to the domestic repercussions of COVID-19 across politics, economy, culture, and education with similar depth while addressing the escalating global pandemic situation. This indicates that both media outlets acknowledged the gravity of the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing its tangible and imminent nature. This convergence on severity is consistent with a broader bipartisan recognition of COVID-19 as a public health threat in the country. This convergence also indicates little evidence of conflict framing at this stage, as both outlets agreed on the seriousness of the pandemic.

Table 1.Comparison of Topic Modeling Results

| Topic |

DongA Ilbo |

Hankyoreh |

Difference |

M % |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

| The Shincheonji Crisis |

833 |

12.35 |

395 |

8.73 |

-3.62 |

10.54 |

| Community Transmission |

352 |

5.22 |

501 |

11.07 |

5.85 |

8.15 |

| Restrictions on Entering a Country |

561 |

8.32 |

348 |

7.69 |

-0.63 |

8.01 |

| Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds |

365 |

5.41 |

376 |

8.31 |

2.90 |

6.86 |

| The Global Surge in Confirmed COVID-19 Case |

539 |

7.99 |

210 |

4.64 |

-3.35 |

6.32 |

| The 21st National Assembly Election |

431 |

6.39 |

253 |

5.59 |

-0.80 |

5.99 |

| Impact on Culture, Entertainment and Sports |

394 |

5.84 |

265 |

5.86 |

0.02 |

5.85 |

| Support for the Recovery of COVID-19 from All Walks of Life |

407 |

6.03 |

225 |

4.97 |

-1.06 |

5.50 |

| The Government’s Regular Briefing on COVID-19 |

450 |

6.67 |

184 |

4.07 |

-2.60 |

5.37 |

| Contraction of the Global Economy by COVID-19 |

302 |

4.48 |

273 |

6.03 |

1.55 |

5.26 |

| Information on COVID-19 |

366 |

5.43 |

199 |

4.40 |

-1.03 |

4.92 |

| Domestic Industry Damage by COVID-19 |

319 |

4.73 |

227 |

5.02 |

0.29 |

4.88 |

| Violations of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Measures |

313 |

4.64 |

214 |

4.73 |

0.09 |

4.69 |

| Everyday News in the COVID-19 Era |

339 |

5.03 |

149 |

3.29 |

-1.74 |

4.16 |

| Impact on Education |

245 |

3.63 |

153 |

3.38 |

-0.25 |

3.51 |

| Criticisms on the Opposition, Conservative Groups, and Conservative Press* |

|

|

217 |

4.80 |

|

|

| President Moon Jae-in’s Performance* |

|

|

169 |

3.73 |

|

|

| Social Distancing* |

|

|

167 |

3.69 |

|

|

| New Technologies for the COVID-19 Era* |

267 |

3.96 |

|

|

|

|

| The Mask Shortage* |

263 |

3.90 |

|

|

|

|

| Total |

6,746 |

100 |

4,525 |

100 |

|

|

Note. The topics marked with asterisks (*) are those that appear in only one newspaper but not the other. Difference indicates Hankyoreh % minus DongA Ilbo %, and M % indicates the mean percentage of DongA Ilbo and Hankyoreh.

Yet, while a majority of the topics were shared, specific subjects were unique to each outlet, and meaningful differences were observed even in common topics based on the depth of coverage. One area where they particularly diverged was in their discussion of prevention techniques. In the early stages of the pandemic, face masks were inadequately supplied in the country, leading to long queues at pharmacies in the early morning. In response to the shortage, the government and ruling party politicians changed their emphasis, stating that “wearing masks is not mandatory to be safe from the virus,” and that the mask shortage is spreading “unnecessary concerns” among the public (T. Kang, 2020). Instead, the government promoted social distancing as the primary prevention measure, restricting activities with a high risk of spreading COVID-19 and enhancing public awareness. In contrast, the leading opposition party criticized the government for advising citizens not to wear a mask if they are healthy due to a lack of mask supply, deeming it a “makeshift policy” that caused public “chaos,” labeling the mask shortage as a “disaster” caused by the clumsy government operation (Yoo, 2020).

These priorities were reflected in the news coverage. Hankyoreh placed more emphasis on “Social Distancing,” echoing the government’s message that this was the best method to prevent infection. In contrast, DongA Ilbo extensively covered “The Mask Shortage,” while that topic did not even emerge as a significant topic in Hankyoreh’s pandemic coverage. Partisan outlets agreed that citizens should be taking steps to fight the disease, but their emphasis coincided with partisan messaging.

The two newspapers also diverged in how they covered groups’ actions. Hankyoreh critiqued institutions and organizations that were uncooperative or critical of the government’s disease prevention measures (the topic “Criticisms on the Opposition, Conservative Groups, and Conservative Press”). The critiques extended to conservative groups, a specific religious organization that violated the social distancing policy and led large-scale anti-government rallies, as well as the leading opposition party and conservative media outlets. Hankyoreh argued that these entities were instigating unnecessary crises and fear among citizens. In contrast, DongA Ilbo maintained its focus on the mask shortage.

Hankyoreh also found ways to emphasize positive messaging of government initiatives. It personalized then-President Moon Jae-in’s strong performance in the topic “President Moon Jae-in’s Performance.” As citizens cooperated with the government’s measures, the spread of the disease gradually came under control, contrasting with the global pandemic situation. Recognized as effective and successful by foreign countries, South Korea’s response to COVID-19 led President Moon to engage in diplomatic activities, holding meetings with leaders of various countries, including President Donald Trump of the United States, to share the country’s know-how in handling the pandemic. This topic also encompassed articles about President Moon actively supporting the relevant authorities and institutions in addressing COVID-19. These actions received much more coverage in Hankyoreh, while DongA Ilbo gave much less attention to the president’s actions.

Hankyoreh also placed greater emphasis on the government’s distribution of relief funds than DongA Ilbo. With COVID-19 rapidly spreading in the country, the government provided emergency disaster relief funds to stabilize the livelihoods of people suffering from the pandemic, including small businesses and freelancers. This initiative aimed to boost consumption, which had contracted due to COVID-19, right before the 2020 legislative election. As one more topic was extracted, the proportions of Hankyoreh’s coverage were mostly smaller or slightly higher than DongA Ilbo’s. In this context, Hankyoreh covered the topic of “Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds” by nearly 3 percentage points more than DongA Ilbo.

The media content analysis indicates that DongA Ilbo and Hankyoreh showcased their political biases through selective coverage, favoring or opposing government-related issues. This differential focus reflects newspaper partisanship. Unlike in other countries, both media outlets in South Korea emphasized the seriousness of the virus, covering the same topics related to the domestic and global spread of COVID-19. While they stressed different methods to combat the disease, both agreed on the necessity of behavioral change for the greater good, aligning with elite messages. This pattern reflects convergence on severity (absence of conflict framing) and divergence in government evaluation (responsibility framing).

Discussion

This study sheds light on how partisan media framed the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea by distinguishing between general coverage of the disease and responsibility attribution for government responses. The findings contribute to framing theory by showing that partisan outlets may converge on issue salience—agreeing on the seriousness of the crisis—while diverging primarily through the responsibility frame, selectively emphasizing government success or failure depending on ideological orientation. This pattern underscores that partisan media bias need not manifest through factual distortion, but through selective emphasis aligned with elite narratives.

This contrast is particularly striking when compared with the United States, where partisan outlets often disputed the very seriousness of the pandemic, a clear manifestation of conflict framing. In South Korea, by contrast, consensus on the severity of COVID-19 shifted partisan divergence toward responsibility attribution. This pattern suggests that crisis framing can vary systematically by institutional and cultural context: where baseline consensus on risk exists, partisan divergence may shift from whether the crisis is severe to who deserves credit or blame for policy outcomes. The distinction matters for democratic accountability because responsibility frames shape evaluations of competence without requiring factual disagreement about the underlying threat.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates the usefulness of automated content analysis in examining partisan bias during crises. While sentiment analysis and LDA topic modeling have limitations, their transparency and replicability make them suitable for exploratory research. Future studies can extend this approach by adopting Structural Topic Modeling (STM) or supervised classification methods to capture subtler patterns of framing.

Substantively, the analysis illustrates how partisan frames shaped public perceptions of government performance, resonating with recent evidence that partisan biases influenced both health-related evaluations and economic perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea (H. Lee, 2025b, 2025a). These connections highlight the significance of media framing in shaping public opinion during crises.

Yet, it is important to note that the media’s relatively unified framing of the virus’s severity may have fostered a broader, cross-partisan sense of national crisis. This shared perception likely heightened public attentiveness to governmental responses. Even though partisan divides in evaluations of government performance persisted (H. Lee, 2025b), the widespread recognition of the pandemic’s gravity—coupled with South Korea’s globally lauded containment strategies—may have contributed to an overall positive public assessment. In this context, the ruling party’s landslide victory in the 2020 legislative election could be interpreted as a reflection of this general approval. While this study does not assert a direct causal link, the interplay between convergent crisis framing, partisan responsibility attribution, and electoral behavior merits further exploration.

Finally, the findings should be understood in the distinctive Korean context. South Korea’s collectivist culture, strong technological infrastructure, and successful “K-Quarantine” policies created a broad consensus on the severity of COVID-19, in contrast to more polarized debates in countries such as the United States. This suggests the value of comparative research to explore whether similar dynamics emerge in countries with different cultural and institutional settings.

Conclusion

This study examined partisan media coverage of COVID-19 in South Korea, showing how conservative and progressive outlets converged on the severity of the pandemic but diverged in attributing responsibility for government responses. The results indicate that, unlike in countries such as the United States, where the conflict frame dominated and even the seriousness of the crisis was contested, partisan bias in South Korea appeared mainly through the responsibility frame. Pro-government media highlighted successful aspects of crisis management, while opposition-aligned outlets emphasized shortcomings such as mask shortages. These findings validate the expectation that partisan outlets in the country, despite sharing consensus on the factual gravity of COVID-19, strategically emphasized or downplayed the government’s performance according to their ideological leanings.

Beyond empirical insights, the findings refine framing theory by demonstrating that partisan bias can emerge not through outright misinformation or factual denial, but through selective emphasis of responsibility attribution. This more nuanced form of bias illustrates how media outlets can influence citizens’ evaluations of governments even when there is a broad consensus on the underlying facts. The study also underscores the practical implications of partisan framing for crisis communication: responsibility attribution is a powerful tool that can affect how citizens perceive both government competence and political accountability. For policymakers, this highlights the importance of transparent and consistent communication; for media professionals, it underlines the ethical responsibility to balance partisan narratives with accurate reporting in times of crisis.

At the same time, the analysis is not without limitations. The study focuses only on the first three months of the pandemic, a period that overlapped with South Korea’s 2020 legislative election. This temporal scope provides valuable insights into partisan dynamics during the early crisis stages but does not capture how narratives evolved over subsequent waves of the pandemic. Future research could extend the analysis to later stages, linking media framing more directly to public opinion outcomes and electoral behavior. Comparative studies across different countries, political systems, and media environments would further illuminate the extent to which convergence on severity and divergence in responsibility attribution is unique to South Korea or part of a broader global pattern. Methodologically, employing advanced techniques such as STM or supervised machine learning could enrich the analysis of partisan frames and provide more precise connections between media narratives and public attitudes. Together, these extensions would build on this study’s contribution to understanding the interplay between partisan media bias, crisis framing, and democratic accountability.

Appendices

Appendix A

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Government Response in South Korea

The first COVID-19 case in South Korea was reported on January 20, 2020. A 35-year-old Chinese woman who had traveled from Wuhan, China, to South Korea was confirmed positive and immediately quarantined. The National Infectious Disease Risk Alert was raised to “Level 2,” and the Central Disease Control Headquarters began operation. In the earliest stage of the pandemic, confirmed cases were limited to travelers from overseas or those who had close contact with confirmed cases. The South Korean government raised its 4-tier Infectious Disease Risk Alert from “Level 2” to “Level 3” on January 27. Yet, the average of newly confirmed cases was about 1.1 per day, and the total number of confirmed cases was only 30 from January 20 to February 17.

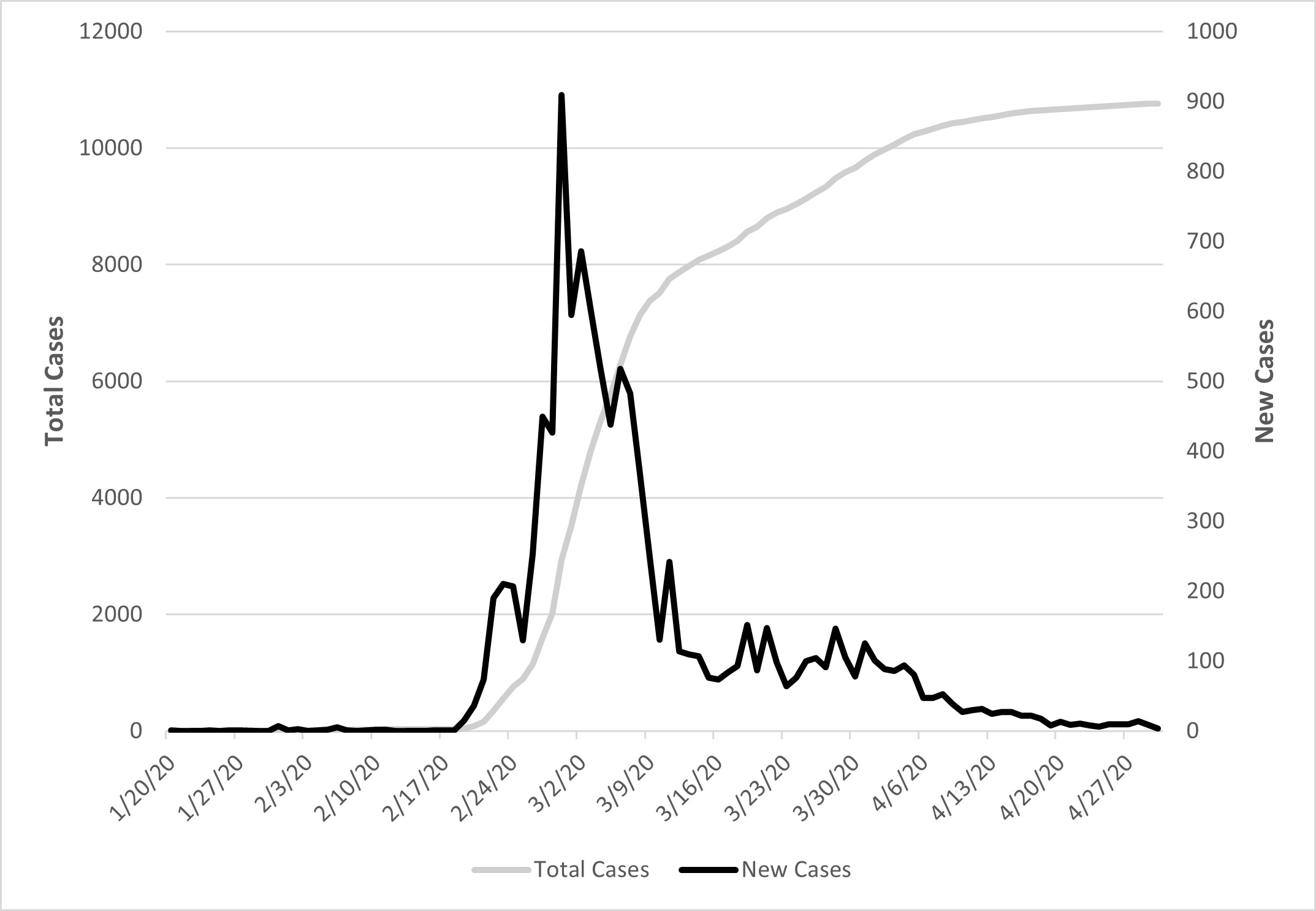

Figure A1.COVID-19 Situation in South Korea from January to April 2020

Note. The data used for the graph is from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/), and the data stopped in April 2020, when the 21st National Assembly Election was held.

It was an outbreak at the Shincheonji Church of Jesus in Daegu that resulted in about 8,000 confirmed cases in Daegu and North Gyeongsang Province through the end of March 2020, which caused the government to declare a severe crisis stage (Hancocks & Seo, 2020). As seen in Figure 7.2, the number of positive cases rapidly increased, with the sudden jump mostly attributed to the Shincheonji Daegu Church and a 61-year-old woman known as “Patient 31” who participated in a gathering at the Church and turned out to be a super spreader (Chang, 2020). By the end of February 2020, South Korea was ranked second after China in the world for confirmed cases, with the number of newly confirmed cases per day hitting a peak at 909 on February 29. The government imposed its highest Infectious Disease Risk Alert, “Level 4,” on February 23, vowing extra resources to the region and limiting public activities. Social distancing measures were first introduced on February 29 to halt the spread of infections.

Amid widespread fears about infection among citizens, the Moon government immediately responded to the pandemic crisis by introducing one of the largest and best-organized epidemic control programs in the world (Bicker, 2020; Normile, 2020). South Korea’s response to COVID-19 is also known as “K-Quarantine,” which collectively refers to South Korea’s successful response system to COVID-19. Specifically, “K-Quarantine” is mainly summarized as a ‘3Ts’—Testing, Tracing, and Treatment—strategy that “consists of robust laboratory diagnostic testing to confirm positive cases, rigorous contact tracing to prevent further spread, and treating those infected at the earliest possible stage” (Government of the Republic of Korea, 2020). The testing and tracing strategies aim at early detection of the virus through preemptive laboratory diagnostic testing and strict epidemiological investigation, considering the potential risk of virus transmission by asymptomatic or mild cases. In addition to early detection of the disease, the treatment strategy classifies patients and provides treatment by the severity of symptoms, leading to low mortality rates and preventing a shortage of hospital beds.

With President Moon giving his full support, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) has taken various innovative measures to implement the ‘3Ts’ strategy that mass tests the population for the virus, isolates any infected people as well as traces and quarantines those they had contact with, and treats patients by symptoms. For instance, in order to enhance the efficiency of mass testing, South Korea introduced the world’s first coronavirus drive-through testing station in tandem with walk-through screening stations on February 28, 2020 (Watson & Jeong, 2020), ahead of March 6 and 10, 2020, when the drive-through coronavirus testing facilities opened for the first time in Wales, the UK, and Seattle, the US, respectively (BBC News, 2020; Lewis, 2020).

Also, the government established and operated a strict epidemiological investigation system to quickly identify the movements of confirmed cases and analyze modes of transmission. To improve the accuracy of epidemiological investigation, when needed, credit card transaction records, CCTV footage, mobile phone GPS data, and other advanced technologies were utilized to trace the paths of confirmed cases and people who had close contact with infected people within the scope permitted by the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. The information found during epidemiological investigations was released anonymously to the public, allowing people to check if they had encountered infected people and get tested if necessary. More importantly, the government covered the cost of COVID-19 testing and treatment for those who met the relevant criteria, encouraging the public to get tested for COVID-19. Treatment for confirmed cases was provided free of charge for citizens and certain foreign nationals.

With the government prioritizing early detection of the virus, coronavirus cases had dropped sharply in South Korea, in contrast with the worldwide situation at the time. With COVID-19 sweeping around the globe, the World Health Organization (WHO) eventually characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020). Contrary to the downward trend of confirmed cases in South Korea, the COVID-19 crisis was becoming more severe and deadly in Europe, the US, and other regions that had to impose lockdowns and close borders.

Appendix B

Procedures for Text Mining Methods

Word Frequency Analysis

For word frequency analysis, I conducted Korean morphological analysis and extracted nouns from the articles of each newspaper using the R package KoNLP (Korean Natural Language Processing).

Sentiment Analysis

The sentiment analysis of articles was performed using the “KNU Sentiment Lexicon,” developed by the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at Kunsan National University. The lexicon comprises a word representing emotion, and polarity representing the intensity of emotion. Words representing emotions consist of a single word, a compound word combining two or more words, and emoticons. Polarity is represented by five integers from +2 to -2, with positive, negative, and neutral words indicated by plus (+), minus (-), and zero (0), respectively. The lexicon includes a total of 14,854 words, consisting of 4,871 positive, 9,829 negative, and 154 neutral words.

Using the R package dplyr, the sentiment lexicon is combined with words used in newspaper articles, assigning each word an emotion score. Unlike word frequency analysis, news articles are tokenized as words, not morphemes, as the sentiment lexicon is word-based. If a word is not in the lexicon, the polarity value becomes NA (Not Applicable), resulting in a score of zero. After assigning emotion scores to each word, the scores are summed to determine the overall emotion expressed in each article.

Topic Modeling Analysis

For topic modeling analysis, I employed hyperparameter tuning to objectively determine the optimal number of topics for each newspaper. Hyperparameter tuning, also known as automatic model tuning, involves finding optimal hyperparameter values for a machine learning algorithm by comparing performance metrics (Yang and Shami, 2020).

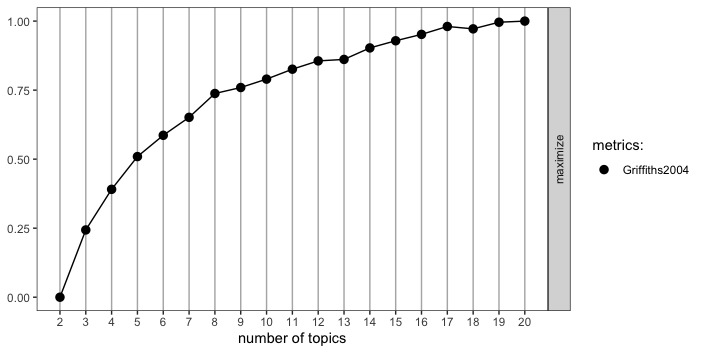

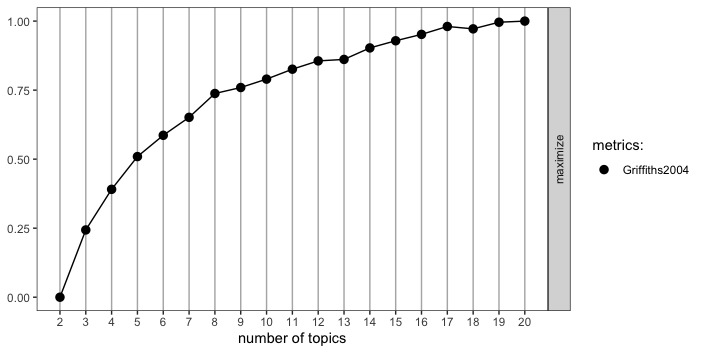

Figure B1.Hyperparameter Tuning Graph of DongA Ilbo

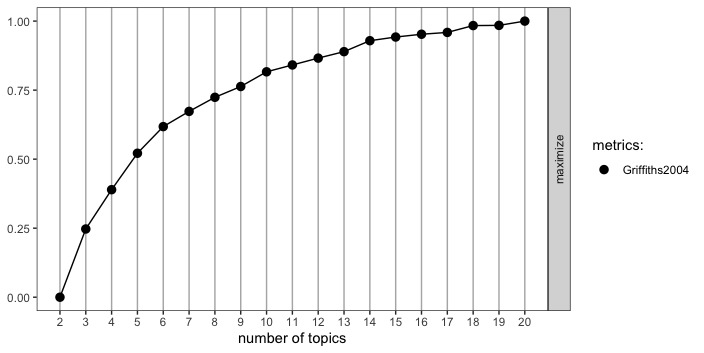

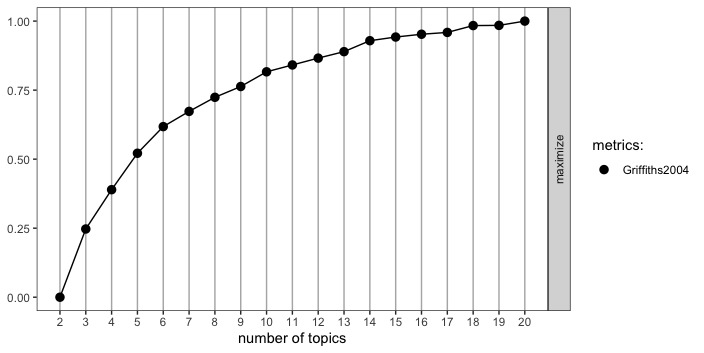

Figure B2.Hyperparameter Tuning Graph of Hankyoreh

Figures B1 and B2 illustrate the performance metrics of the LDA model based on the number of topics for each newspaper. The performance metric “Griffiths2004” reflects the perplexity of how well the model explains the corpus. A higher value of Griffiths2004 indicates better model performance in explaining the corpus structure, with values ranging from 0 to 1. The closer the metric is to 1, the more effectively the model performs.

It is advisable to set the number of topics at a point where the performance ceases to improve significantly and begins to fluctuate, even as the number of topics increases. Upon examination of the graphs, the metric for DongA Ilbo newspaper articles starts to fluctuate when the number of topics is 17, whereas the metric for Hankyoreh newspaper articles begins to stagnate without notable improvement at the point where the number of topics is 18 (refer to Table B1 for precise values of Griffiths2004 metrics).

Based on the results of hyperparameter tuning, I set the number of topics (k) as 17 topics for DongA Ilbo and 18 topics for Hankyoreh. The LDA model was built using Gibbs sampling with the R package topicmodels.

Table B1.Griffiths2004 Metrics

| Number of Topics |

Griffiths2004 |

| DongA Ilbo |

Hankyoreh |

| 20 |

-697854.7 |

-1080204 |

| 19 |

-697797.6 |

-1078442 |

| 18 |

-696075.5 |

-1078744 |

| 17 |

-695993.0 |

-1077163 |

| 16 |

-695206.6 |

-1077129 |

| 15 |

-695644.4 |

-1076730 |

| 14 |

-695553.3 |

-1077570 |

| 13 |

-695881.1 |

-1080168 |

| 12 |

-695978.9 |

-1080960 |

| 11 |

-697951.0 |

-1083265 |

| 10 |

-699264.0 |

-1085851 |

| 9 |

-700751.5 |

-1089340 |

| 8 |

-703522.2 |

-1094203 |

| 7 |

-707431.5 |

-1099004 |

| 6 |

-712463.9 |

-1107515 |

| 5 |

-719419.9 |

-1116195 |

| 4 |

-728109.3 |

-1131389 |

| 3 |

-742135.4 |

-1151464 |

| 2 |

-763628.2 |

-1184882 |

Appendix C

Comparison of Word Frequency Analysis

Table C1.Top 20 Words by Newspaper (in translation)

| DongA Ilbo |

Hankyoreh |

| Word |

N |

Word |

N |

| COVID-19 |

21,847 |

Confirmed Case |

6,512 |

| Patient |

8,640 |

COVID-19 |

6,209 |

| Tested Positive |

7,812 |

Tested Positive |

5,835 |

| China |

6,669 |

Government |

5,292 |

| Government |

6,201 |

Patient |

5,208 |

| Confirmed Case |

5,982 |

China |

4,628 |

| Spread |

5,317 |

Quarantine |

3,693 |

| Infection |

4,879 |

Support |

3,691 |

| Quarantine |

4,683 |

Daegu |

3,646 |

| Mask |

4,565 |

Spread |

3,643 |

| Situation |

4,164 |

Infection |

3,573 |

| Hospital |

3,965 |

Hospital |

3,401 |

| Testing |

3,879 |

Mask |

3,247 |

| Support |

3,802 |

Testing |

3,167 |

| South Korea |

3,782 |

Local |

3,164 |

| Local |

3,553 |

Situation |

3,099 |

| Daegu |

3,411 |

Prevention and Control |

3,057 |

| The United States |

3,400 |

Seoul |

3,005 |

| Prevention and Control |

3,380 |

South Korea |

2,839 |

| Seoul |

3,378 |

The United States |

2,715 |

Table C1 presents the results of the word frequency analysis comparing both media outlets. After preprocessing the corpus and eliminating “stop words,” which are a set of commonly used words in a language but carry little significant meaning, a total of 43,580 nouns were extracted from 6,746 DongA Ilbo articles, and a total of 43,050 nouns were extracted from 4,525 Hankyoreh articles. The comparison shows that there are more similarities than differences, as the top 20 major words are identical for both newspapers. This result is understandable since the collected articles are about the same pandemic affecting the country during the same period. However, there are noticeable differences in the order of word frequency, which can indirectly infer what aspects of the pandemic situation each newspaper wanted to emphasize more.

Comparing the top 20 most frequently used words in articles of each newspaper, the word “COVID-19” was used overwhelmingly more in DongA Ilbo newspaper articles, appearing 21,847 times in 6,746 articles. On the other hand, even though all the articles collected for analysis are about the COVID-19 pandemic, “COVID-19” was not the most frequently used word in Hankyoreh newspaper articles. In the Hankyoreh, the most frequently used word was “confirmed case,” which appeared 6,512 times in 4,525 articles, outstripping “COVID-19” (6,209 times). Comparing the order of word frequency, it is also noteworthy that the words “patient” and “China” were more frequently used in the COVID-19 articles of DongA Ilbo, while “government” and “support” were more frequently used in Hankyoreh newspaper articles.

Appendix D

Topic Modeling Results

Table D1 shows the topic modeling result of 6,746 DongA Ilbo newspaper articles about the COVID-19 pandemic released from the day after the first confirmed case was reported to the day before the 21st National Assembly Election (from January 21 to April 14, 2020). Likewise, Table D2 shows the topic modeling result of 4,525 Hankyoreh newspaper articles about the COVID-19 pandemic released during the same period. Each of the top 20 major words on the right side of the table is one that has the highest beta (ß) for the given topic among all the words. Beta (ß) refers to the probability that a word will appear in each topic.

Table D3 shows beta (ß) values for the major words of all the topics. The words “COVID-19” and “South Korea” were included as the top major words for almost all the topics since all the articles are about the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Thus, they were excluded together with stop words that carry little substantive meaning. The words are listed in the order of beta (ß) from the largest to the smallest within each top 20 words group. The names of topics on the left are assigned after considering the semantic relevance of the words and directly looking at the articles that have the highest gamma (γ) for the given topic among all the articles. Gamma (γ) refers to the probability that a document will appear in each topic. Topics are numbered according to the sequence extracted during the topic modeling process.

Table D1.Topic Modeling Result of DongA Ilbo Newspaper

| Topic |

Top 20 Major Words |

| 1 |

Community Transmission (Local Spread) |

Seoul, Visit, Employee, Gyeonggi-do, Confirmed Case, Region, Use, Contact, Busan, Participation, Facility, Infection, Closed, Work, Disinfection, Infectious Disease, Incheon, Building, Path of Confirmed Case, Access |

| 2 |

Support for the Recovery of COVID-19 from All Walks of Life |

Deliver, Support, Region, Nationwide, Hardships, Spread, Overcome, Mask, Prevention, Daegu, Help, Plan, Operation, Vulnerable Groups, Goods, Centers, Donation, Facility, Join, Life |

| 3 |

The Global Surge in Confirmed COVID-19 Case |

the United States, the World, Local, President, Italy, Mortality, Confirmed Case, France, Spread, Country, Trump, Europe, England, Response, Coverage, Control, Concern, Virus, Outbreak, Spain |

| 4 |

Domestic Industry Damage by COVID-19 |

Domestic, Companies, Conjuncture, Business, Production, Shutting Down, Decrease, Car, Factory, Situation, Impact, Hyundai, China, Operation, Industry, Spread, Setback, Employee, Aviation Industry, Management |

| 5 |

Violations of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Measures |

Police, Taking Action, Request, Investigation, Explanation, Guideline, Spread, Telephone, Cooperation, Infectious Disease, Position, Information, Management, Violation, Shincheonji, Prevention, Report, Argument, Making Public, Public Officials |

| 6 |

Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds |

Support, Government, Emergency, Economy, Measures, Payment, Countermeasures, Hardships, Meetings, Expansion, Damage, Small Business, Burden, Announcement, Scale, Leveling Off, Budget, Application, Funds, Plan |

| 7 |

New Technologies for the COVID-19 Era |

Utilization, Development, Service, System, Method, Technology, Change, Online, Base, Strengthening, Field, Share, Introduction, Application, Build, Choice, Attention, Focus, Research, Improvement |

| 8 |

Restrictions on Entering a Country |

China, Entry, Wuhan, Government, Japan, Hubei, Taking Action, Korean, Country, Prohibition, Chinese, Spread, Returning from Abroad, Travel, Restriction, Quarantine, Authorities, Foreign Country, Airport, Arrival |

| 9 |

The Government’s Regular Briefing on COVID-19 |

Disease Control, Countermeasures, Central, Headquarters, Government, Management, Safety, Briefing, Confirmed Case, Outbreak, Domestic, Explanation, Response, Situation, Disaster, Local Community, Patient, Quarantine, Disease, Ministry of Health |

| 10 |

The Shincheonji Crisis |

Tested Positive, Testing, Patient, Hospital, Quarantine, Symptoms, Confirmed Case, Screening Clinic, Treatment, Infection, Outbreak, Daegu, Negative, Hospitalization, Positive, Suspected, Health Authority, Contact, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), Medical Staff |

| 11 |

Impact on Culture, Entertainment, and Sports |

Games, Spread, Host, Cancellation, Delay of Schedule, Suspension, Record, League, the United States, Events, Sports, Aftermath, Pro, the Olympics, Athletes, Training, Competition, Participation, Crowdless, Tokyo |

| 12 |

Impact on Education |

Education, Spread, Postponement, School, Student, Situation, Announcement, Seoul, Concern, Beginning of School, Period, University, Nationwide, Operation, Schedule, Consideration, Online, Cancellation, Classes, Cram School |

| 13 |

Information on COVID-19 |

Virus, Respiratory Syndrome, Infection, Expert, Professor, Possibility, Risk, Infectious Disease, Disease, MERS, Patient, China, Severe, Prevention, Middle East, Health, Effects, Pointing Out, Analysis, Cause |

| 14 |

The 21st National Assembly Election |

United Future Party, President, the Democratic Party of Korea, Citizen, Moon Jae-in, General Election, Cheongwadae [the Blue House: Korean Presidential residence), Criticism, Politics, Election, Candidate, the National Assembly, Remark, Conjuncture, Situation, Political Party, Emphasis, Response, Vote, Argument |

| 15 |

Everyday News in the COVID-19 Era |

Thoughts, Society, Mind, Beginning, Social Distancing, Concern, Story, Culture, Daily Life, Family, Broadcasting, Spirit, Conjuncture, Gratitude, Movie, Efforts, Citizen, Response, Message, Experience |

| 16 |

The Mask Shortage |

Mask, Spread, Sales, Purchase, Operation, Conjuncture, Customer, Restaurant, Employee, Order, Visit, Seoul, Price, Phenomenon, Shortage, Surge, Citizen, Pharmacy, Supply, Online |

| 17 |

Contraction of the Global Economy by COVID-19 |

Prospect, Concern, Market, Economy, Forecast, Business, Finance, Drop, Spread, Situation, the United States, Investment, Influence, Global, Impact, Volume, Decrease, Analysis, the World, Trading |

Table D2.Topic Modeling Result of Hankyoreh Newspaper

| Topic |

Top 20 Major Words |

| 1 |

Support for the Recovery of COVID-19 from All Walks of Life |

Deliver, Support, Region, Mask, Hardships, Vulnerable Groups, Nationwide, Participation, Overcome, Donation, Organizations, Goods, Daegu, Citizen, Hope, Foundations, Contribution, the Elderly, Relief, Social Welfare |

| 2 |

Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds |

Support, Emergency, Payment, Government, Economy, Small Business, Hardships, Measures, Damage, Income, Worder, Expansion, Budget, Pushing Ahead, Burden, Plan, Leveling Off, Business, Countermeasures, Funds |

| 3 |

The Shincheonji Crisis |

Daegu, Patient, Tested Positive, Hospital, Confirmed Case, Gyeongbuk (North Gyeongsang Province), Treatment, Medical Staff, Hospitalization, Quarantine, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Sickbed, Mortality, Outbreak, Region, Headquarters, Domestic, Central, Countermeasures, Symptoms |

| 4 |

Impact on Education |

Education, School, Delay, Student, Online, University, Nationwide, Beginning of School, Operation, Utilization, Society, Schedule, Consideration, Situation, Seoul, Period, Begin, Preparation, Classes, Kindergarten |

| 5 |

Impact on Culture, Entertainment, and Sports |

Games, Delay, Cancelation, Schedule, Director, Broadcasting, Spread, Discontinuity, Movie, Conjuncture, Participation, Events, Program, Exhibition, Athlete, Production, Sports, League, Performance |

| 6 |

Everyday News in the COVID-19 Era |

Thoughts, Mind, Concern, Family, Story, News, Anxiety, Life, Friend, Daily Life, Way, Child, Surroundings, Situation, Service, Face, Voice, Activity, Help, Pain |

| 7 |

President Moon Jae-in’s Performance |

Response, Emphasis, Situation, Government, Conference, President, Efforts, Citizen, Moon Jae-in, Discussion, Cooperation, Conjuncture, Problem, Cheongwadae (the Blue House: the Korean presidential residence), Support, Request, Evaluation, Proposal, Country, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control |

| 8 |

The 21st National Assembly Election |

United Future Party, the Democratic Party of Korea, Citizen, General Election, the National Assembly, Election, Candidate, Criticism, Politics, President, Political Party, Policy, Vote, Conjuncture, Remark, Member of the National Assembly, Seoul, Voter, Conservative, the Opposition |

| 9 |

The Government’s Regular Briefing on COVID-19 |

Countermeasures, Safety, Government, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Situation, Response, Management, Central, Headquarters, Spread, Examination, Explanation, Level, Possibility, Measures, Disaster, Local Community, Breaking the Chain of Infection, Authorities, Taking Action |

| 10 |

Restrictions on Entering a Country |

China, Entry, Japan, Government, Wuhan, Country, Foreign Country, Spread, Returning from Abroad, Hubei, Korean, Border Screening, Chinese, Arrival, Authorities, Airport, Entrant, Flights, Travel, Quarantine |

| 11 |

Information on COVID-19 |

Virus, Infection, Expert, Professor, China, Disease, Case, Research, Possibility, Information, Outbreak, MERS, Spread, Infectious Disease, Explanation, Risk, Epidemic, Analysis, Health, Pneumonia |

| 12 |

The Global Surge in Confirmed COVID-19 Case |

The United States, Country, the World, Trump, Spread, Europe, England, Italy, Confirmed Case, President, Media, Control, Announcement, France, Restriction, New York, Population, Reuter’s News Agency, Mortality, Spain |

| 13 |

Contraction of the Global Economy by COVID-19 |

Influence, Prospect, Market, Decrease, Economy, Forecast, Finance, Announcement, Impact, Spread, Concern, Investment, Global, Levelling Off, Drop, Business, Dollar, Record, Increase, Contraction |

| 14 |

Domestic Industry Damage by COVID-19 |

Companies, Sales, Production, Supply, Demand, Plan, Domestic, Factory, Secure, Car, Industry, Purchase, Supply and Demand, Situation, Operation, Mask, Quantity of Supply, Shutting Down, Hyundai, Customer |

| 15 |

Community Transmission (Local Spread) |

Tested Positive, Screening Clinic, Testing, Quarantine, Confirmed Case, Symptoms, Self-Quarantine, Contact, Positive, Public Health Center, Infection, Negative, Visit, Investigation, Close Contact, Epidemiological Investigation, Family, Woman, Fever, Health Authority |

| 16 |

Criticisms on the Opposition, Conservative Groups, and Conservative Press |

Society, Problem, Reality, Change, Era, Solve, Country, History, Argument, Thoughts, Reason, the Press, Meaning, Hatred, Opportunity, Fear, Way, Politics, Humanity, the World |

| 17 |

Violations of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Measures |

Police, Spread, Seoul, Investigation, Violation, Infectious Disease, Rally, Shincheonji, Organizations, Suspicion, Religion, Citizen, Telephone, Church, Accusation, Public Officials, Law, Prohibition, Interference with Business, Request |

| 18 |

Social Distancing |

Seoul, Social Distancing, Mask, Spread, Citizen, Facility, Use, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Measures, Employee, Operation, Installation, Infection, Wearing, Visit, Notice, Space, Gyeonggi-do, Prevention, Refrain, Concern |

Table D3.Beta (ß) Values of the Major Words

| DongA Ilbo |

Hankyoreh |

| Word |

Beta (ß) |

Word |

Beta (ß) |

| 1. Community Transmission |

1. Support for the Recovery of COVID-19 from All Walks of Life |

| Seoul |

.02230 |

Deliver |

.01440 |

| Visit |

.01240 |

Support |

.01380 |

| Employee |

.01120 |

Region |

.01280 |

| Gyeonggi-do Province |

.01100 |

Nationwide |

.01120 |

| Confirmed Case |

.01020 |

Hardships |

.00929 |

| Region |

.00953 |

Spread |

.00873 |

| Use |

.00911 |

Overcome |

.00846 |

| Contact |

.00869 |

Mask |

.00801 |

| Busan |

.00845 |

Prevention |

.00785 |

| Participation |

.00820 |

Daegu |

.00779 |

| Facility |

.00757 |

Help |

.00774 |

| Infection |

.00749 |

Plan |

.00769 |

| Closed |

.00686 |

Operation |

.00761 |

| Work |

.00676 |

Vulnerable Groups |

.00745 |

| Disinfection |

.00647 |

Goods |

.00691 |

| Infectious Disease Prevention and Control |

.00598 |

Centers |

.00654 |

| Incheon |

.00590 |

Donation |

.00638 |

| Building |

.00571 |

Facility |

.00574 |

| Routes |

.00544 |

Join |

.00566 |

| Access |

.00532 |

Life |

.00526 |

| 2. Support Activities for the Recovery of COVID-19 from All Walks of Life |

2. Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds |

| Deliver |

.01440 |

Support |

.01680 |

| Support |

.01380 |

Emergency |

.01100 |

| Region |

.01280 |

Payment |

.01030 |

| Nationwide |

.01120 |

Government |

.01000 |

| Hardships |

.00929 |

Economy |

.01000 |

| Spread |

.00873 |

Small Business |

.00701 |

| Overcome |

.00846 |

Hardships |

.00698 |

| Mask |

.00801 |

Measures |

.00630 |

| Prevention |

.00785 |

Damage |

.00578 |

| Daegu |

.00779 |

Income |

.00570 |

| Help |

.00774 |

Worker |

.00567 |

| Plan |

.00769 |

Expansion |

.00543 |

| Operation |

.00761 |

Budget |

.00541 |

| vulnerable groups |

.00745 |

Pushing Ahead |

.00538 |

| Goods |

.00691 |

Burden |

.00522 |

| Centers |

.00654 |

Plan |

.00512 |

| Donation |

.00638 |

Stability |

.00507 |

| Facility |

.00574 |

Business |

.00483 |

| Join |

.00566 |

Countermeasures |

.00470 |

| Life |

.00526 |

Funds |

.00462 |

| 3. The Global Surge in Confirmed COVID-19 Case |

3. The Shincheonji Crisis |

| the United States |

.01850 |

Daegu |

.03980 |

| the World |

.01400 |

Patient |

.02680 |

| Local |

.01090 |

Tested Positive |

.02480 |

| President |

.00874 |

Hospital |

.02210 |

| Italy |

.00822 |

Confirmed Case |

.01940 |

| Mortality |

.00738 |

Gyeongbuk |

.01850 |

| Confirmed Case |

.00721 |

Treatment |

.01770 |

| France |

.00668 |

Medical Staff |

.01310 |

| Spread |

.00655 |

Hospitalization |

.01200 |

| Country |

.00640 |

Quarantine |

.01120 |

| Trump |

.00633 |

Infectious Disease Prevention and Control |

.01030 |

| Europe |

.00618 |

Sickbed |

.00903 |

| England |

.00607 |

Mortality |

.00897 |

| Response |

.00599 |

Outbreak |

.00870 |

| Coverage |

.00500 |

Region |

.00868 |

| Control |

.00472 |

Headquarters |

.00779 |

| Concern |

.00464 |

Domestic |

.00708 |

| Virus |

.00427 |

Central |

.00687 |

| Outbreak |

.00423 |

Countermeasures |

.00640 |

| Spain |

.00399 |

Symptoms |

.00583 |

| 4. Domestic Industry Damage by COVID-19 |

4. Impact on Education |

| Domestic |

.01330 |

Education |

.01600 |

| Companies |

.01060 |

School |

.01490 |

| Conjuncture |

.00986 |

Delay |

.01030 |

| Business |

.00885 |

Student |

.01010 |

| Production |

.00775 |

Online |

.00987 |

| Shutting Down |

.00770 |

University |

.00879 |

| Decrease |

.00704 |

Nationwide |

.00857 |

| Car |

.00702 |

Beginning of School |

.00834 |

| Factory |

.00697 |

Operation |

.00760 |

| Situation |

.00680 |

Utilization |

.00726 |

| Impact |

.00607 |

Society |

.00704 |

| Hyundai |

.00536 |

Schedule |

.00682 |

| China |

.00511 |

Consideration |

.00648 |

| Operation |

.00506 |

Situation |

.00637 |

| Industry |

.00480 |

Seoul |

.00633 |

| Spread |

.00477 |

Period |

.00600 |

| Setback |

.00470 |

Begin |

.00555 |

| Employee |

.00460 |

Preparation |

.00551 |

| Aviation Industry |

.00448 |

Classes |

.00525 |

| Management |

.00438 |

Kindergarten |

.00462 |

| 5. Violations of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Measures |

5. Impact on Culture, Entertainment, and Sports |

| Police |

.01020 |

Games |

.00825 |

| Taking Action |

.00895 |

Delay |

.00751 |

| Request |

.00863 |

Cancellation |

.00744 |

| Investigation |

.00754 |

Schedule |

.00604 |

| Explanation |

.00727 |

Director |

.00492 |

| Policy |

.00714 |

Broadcasting |

.00473 |

| Spread |

.00687 |

Spread |

.00430 |

| Telephone |

.00687 |

Discontinuity |

.00411 |

| Cooperation |

.00647 |

Movie |

.00411 |

| Infectious Disease |

.00548 |

Conjunction |

.00391 |

| Position |

.00529 |

Culture |

.00384 |

| Information |

.00519 |

Participation |

.00376 |

| Management |

.00505 |

Events |

.00364 |

| Violation |

.00505 |

Program |

.00349 |

| Shincheonji |

.00484 |

Exhibition |

.00341 |

| Prevention |

.00441 |

Athlete |

.00333 |

| Report |

.00438 |

Production |

.00333 |

| Argument |

.00438 |

Sports |

.00318 |

| Making Public |

.00430 |

League |

.00314 |

| Public Officials |

.00430 |

Performance |

.00298 |

| 6. Emergency Coronavirus Relief Funds |

6. Everyday News in the COVID-19 Era |

| Support |

.01970 |

Thoughts |

.01060 |

| Government |

.01330 |

Mind |

.00942 |

| Emergency |

.01230 |

Concern |

.00707 |

| Economy |

.01070 |

Family |

.00577 |

| Measures |

.00960 |

Story |

.00499 |

| Payment |

.00824 |

News |

.00486 |

| Countermeasures |

.00731 |

Anxiety |

.00466 |

| Hardships |

.00712 |

Life |

.00414 |

| Meetings |

.00708 |

Friend |

.00411 |

| Expansion |

.00668 |

Daily Life |

.00404 |

| Damage |

.00666 |

Way |

.00339 |

| Small Business |

.00633 |

Child |

.00329 |

| Burden |

.00593 |

Surroundings |

.00323 |

| Announcement |

.00575 |

Situation |

.00316 |

| Scale |

.00568 |

Service |

.00287 |

| Leveling Off |

.00563 |

Face |

.00287 |

| Budget |

.00544 |

Voice |

.00277 |

| Application |

.00537 |

Activity |

.00271 |

| Funds |

.00500 |

Help |

.00268 |

| Plan |

.00495 |

Pain |

.00268 |

| 7. New Technologies for the COVID-19 Era |

7. President Moon Jae-in's Performance |

| Utilization |

.00782 |

Response |

.01610 |

| Development |

.00721 |

Emphasis |

.01420 |

| Service |

.00663 |

Situation |

.01340 |

| System |

.00658 |

Government |

.01320 |

| Method |

.00635 |

Conference |

.01080 |

| Technology |

.00618 |

President |

.01060 |

| Change |

.00525 |

Effort |

.01050 |

| Online |

.00471 |

Citizen |

.00999 |

| Base |

.00467 |

Moon Jae-in |

.00846 |

| Strengthening |

.00425 |

Discussion |

.00765 |

| Field |

.00420 |

Cooperation |

.00752 |

| Share |

.00408 |

Conjuncture |

.00745 |

| Introduction |

.00397 |

Problem |

.00729 |

| Application |

.00387 |

Cheongwadae |

.00706 |

| Build |

.00387 |

Support |

.00657 |

| Choice |

.00378 |

Request |

.00618 |

| Attention |

.00371 |

Evaluation |

.00599 |

| Focus |

.00369 |

Proposal |

.00566 |

| Research |

.00352 |

Country |

.00534 |

| Improvement |

.00352 |

Infectious Disease Prevention and Control |

.00534 |

| 8. Restrictions on Entering a Country |

8. The 21st National Assembly Election |

| China |

.02440 |

United Future Party |

.02120 |

| Entry |

.01720 |

The Democratic Party of Korea |

.01230 |

| Wuhan |

.01600 |

Citizen |

.00959 |

| Government |

.01360 |

General Election |

.00852 |

| Japan |

.01260 |

The National Assembly |

.00762 |

| Hubei |

.01230 |

Election |

.00705 |

| Taking Action |

.01230 |

Candidate |

.00680 |

| Korean |

.00936 |

Criticism |

.00577 |

| Country |

.00887 |

Politics |

.00564 |

| Prohibition |

.00881 |

President |

.00489 |

| Chinese |

.00878 |

Political Party |

.00473 |

| Spread |

.00808 |

Policy |

.00470 |

| Returning from Abroad |

.00741 |

Vote |

.00436 |

| Travel |

.00741 |

Conjuncture |

.00430 |

| Restriction |

.00728 |

Remark |

.00411 |

| Quarantine |

.00647 |

Member of the National Assembly |

.00392 |

| Authorities |

.00647 |

Seoul |

.00389 |

| Foreign Country |

.00645 |

Voter |

.00373 |

| Airport |

.00622 |

Conservative |

.00361 |

| Arrival |

.00537 |

The Opposition |

.00345 |

| 9. The Government’s Regular Briefing on COVID-19 |

9. The Government’s Regular Briefing on COVID-19 |

| Disease Control |

.02510 |

Countermeasures |

.02300 |

| Countermeasures |

.02350 |

Safety |

.01720 |

| Central |

.01830 |

Government |

.01540 |

| Headquarters |

.01780 |

Infectious disease prevention and control |

.01380 |

| Government |

.01390 |

Situation |

.01310 |

| Management |

.01370 |

Response |

.01240 |

| Safety |

.01360 |

Management |

.01210 |

| Briefing |

.01190 |

Central |

.01190 |

| Confirmed Case |

.01190 |

Headquarters |

.01130 |

| Outbreak |

.01140 |

Spread |

.01070 |

| Domestic |

.00991 |

Examination |

.01000 |

| Explanation |

.00888 |

Explanation |

.00957 |

| Response |

.00869 |

Level |

.00906 |

| Situation |

.00832 |

Possibility |

.00873 |

| Disaster |

.00824 |

Measures |

.00864 |

| Local Community |

.00772 |

Disaster |

.00858 |

| Patient |

.00738 |

Local Community |

.00792 |

| Quarantine |

.00729 |

Breaking the Chain of Infection |

.00786 |

| Disease |

.00704 |

Authorities |

.00783 |

| Ministry of Health and Welfare |

.00704 |

Taking Action |

.00777 |

| 10. The Shincheonji Crisis |

10. Restrictions on Entering a Country |

| Tested Positive |

.05550 |

China |

.02070 |

| Testing |

.02400 |

Entry |

.01700 |

| Patient |

.02330 |

Japan |

.01250 |

| Hospital |

.02090 |

Government |

.01150 |

| Quarantine |

.02000 |

Wuhan |

.01140 |

| Symptoms |

.01670 |

Country |

.00947 |

| Confirmed Case |

.01590 |

Foreign Country |

.00903 |

| Screening Clinic |

.01330 |

Spread |

.00824 |

| Treatment |

.01330 |

Returning from Abroad |

.00762 |

| Infection |

.01050 |

Hubei |

.00747 |

| Outbreak |

.01030 |

Korean |

.00724 |

| Daegu |

.01000 |

Border Screening |

.00691 |

| Negative |

.00960 |

Chinese |

.00680 |

| Hospitalization |

.00960 |

Arrival |

.00647 |

| Positive |

.00944 |

Authorities |

.00632 |

| Suspected |

.00930 |

Airport |

.00600 |

| Health Authority |

.00892 |

Entrant |

.00600 |

| Contact |

.00789 |

Flights |

.00585 |

| Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) |

.00786 |

Travel |

.00582 |

| Medical Staff |

.00777 |

Quarantine |

.00550 |

| 11. Impact on Culture, Entertainment and Sports |

11. Information on COVID-19 |

| Games |

.01080 |

Virus |

.01600 |

| Spread |

.00894 |

Infection |

.01220 |

| Host |

.00841 |

Expert |

.00962 |

| Cancellation |

.00735 |

Professor |

.00831 |

| Delay of Schedule |

.00680 |

China |

.00806 |

| Suspension |

.00657 |

Disease |

.00779 |

| Record |

.00588 |

Case |

.00757 |

| League |

.00499 |

Research |

.00751 |

| the United States |

.00496 |

Possibility |

.00690 |

| Events |

.00482 |

Information |

.00660 |

| Sports |

.00451 |

Outbreak |

.00632 |

| Aftermath |

.00432 |

MERS |

.00617 |

| Pro |

.00432 |

Spread |

.00605 |

| the Olympics |

.00418 |

Infectious Disease |

.00565 |

| Athletes |

.00418 |

Explanation |

.00538 |

| Training |

.00418 |

Risk |

.00538 |

| Competition |

.00404 |

Epidemic |

.00501 |

| Participation |

.00385 |

Analysis |

.00495 |

| Crowdless |

.00371 |

Health |

.00483 |

| Tokyo |

.00359 |

Pneumonia |

.00449 |

| 12. Impact on Education |

12. The Global Surge in Confirmed COVID-19 Case |

| Education |

.01320 |

the United States |

.02540 |

| Spread |

.01290 |

Country |

.01250 |

| Postponement |

.01290 |

the World |

.01150 |

| School |

.01210 |

Trump |

.01120 |

| Student |

.00985 |

Spread |

.01040 |

| Situation |

.00974 |

Europe |

.00908 |

| Announcement |

.00966 |

England |

.00853 |

| Seoul |

.00872 |

Italy |

.00769 |

| Concern |

.00858 |

Confirmed Case |

.00618 |

| Beginning of School |

.00845 |

President |

.00573 |

| Period |

.00801 |

Media |

.00573 |

| University |

.00781 |

Control |

.00570 |

| Nationwide |

.00765 |

Announcement |

.00547 |

| Operation |

.00757 |

France |

.00547 |

| Schedule |

.00757 |

Restriction |

.00483 |

| Consideration |

.00702 |

New York |

.00460 |

| Online |

.00660 |

Population |

.00457 |

| Cancellation |

.00451 |

Reuter's News Agency |

.00431 |

| Classes |

.00446 |

Mortality |

.00425 |

| Cram School |

.00427 |

Spain |

.00425 |

| 13. Information on COVID-19 |

13. Contraction of the Global Economy by COVID-19 |

| Virus |

.01700 |

Influence |

.00997 |

| Respiratory Syndrome |

.01180 |

Prospect |

.00856 |

| Infection |

.01180 |

Market |

.00850 |

| Expert |

.01160 |

Decrease |

.00832 |

| Professor |

.01040 |

Economy |

.00800 |

| Possibility |

.00806 |

Forecast |

.00797 |

| Risk |

.00687 |

Finance |

.00746 |

| Infectious Disease |

.00665 |

Announcement |

.00725 |

| Disease |

.00657 |

Impact |

.00588 |

| MERS |

.00650 |

Spread |

.00579 |

| Patient |

.00646 |

Concern |

.00528 |

| China |

.00635 |

Investment |

.00528 |

| Severe |

.00587 |

Global |

.00525 |

| Prevention |

.00570 |

Levelling Off |

.00501 |

| Middle East |

.00559 |

Drop |

.00498 |

| Health |

.00526 |

Business |

.00475 |

| Effect |

.00526 |

Dollar |

.00469 |

| Pointing Out |

.00524 |

Record |

.00469 |

| Analysis |

.00513 |

Increase |

.00460 |

| Cause |

.00513 |

Contraction |

.00433 |

| 14. The 21st National Assembly Election |

14. Domestic Industry Damage by COVID-19 |

| United Future Party |

.01830 |

Companies |

.00913 |

| President |

.01170 |

Sales |

.00867 |

| the Democratic Party of Korea |

.01150 |

Production |

.00838 |

| Citizen |

.01080 |

Supply |

.00714 |

| Moon Jae-in |

.00911 |

Demand |

.00576 |

| General Election |

.00762 |

Plan |

.00576 |

| Cheongwadae (the Blue House) |

.00699 |

Domestic |

.00561 |

| Criticism |

.00686 |

Factory |

.00554 |

| Politics |

.00647 |

Secure |

.00512 |

| Election |

.00602 |

Car |

.00494 |

| Candidate |

.00556 |

Industry |

.00483 |

| the National Assembly |

.00493 |

Purchase |

.00483 |

| Remark |

.00474 |

Supply and Demand |

.00476 |

| Conjuncture |