In combating COVID-19, South Korea and Taiwan have been termed as the models of “agile governance,” referring to an adaptive, data-driven, and inclusive multi-stakeholder approach (Manantan, 2020). However, the concern about how to ensure individual liberty given the strict oversight was raised in both countries. In Taiwan, the government traces the footprints of confirmed cases but refuses to release personal information for the protection of privacy and encourages potentially infected people to turn themselves in. The South Korean government reveals detailed information about infected people’s movements, but some question whether it is useful and are concerned about the possible infringement of human rights (Zastrow, 2020). So far, both countries have successfully contained the disease, but the controversy on privacy involved in digital tracing is still lingering, not only in Taiwan and South Korea, but also in other contexts. The governments of Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand have all developed apps that may share phone owners’ contact list and travel histories with the health authorities (AEIdeas, 2020). To better guard individual privacy, Germany instead rolled out an app that only received warning from the central server if phone owners were in contact with the infected person for at least 15 minutes (Schmidt, 2020).

This paper sets out the policy of releasing individual information as a test to see whether there is a trade-off between these values: social surveillance, collective security, and privacy. In Taiwan, it has been highly debated whether releasing infected people’s information as a means of social monitoring could reduce the risk of the virus spreading, or increase the risk of stigmatizing infected people, which is not conducive to collective security. In this time of crisis, the government might implement harsh interventions, which might contradict democratic values and civil liberties. Have people with democratic values been less likely to accept releasing individual information out of concern for privacy? Have people concerned about collective security been more willing to accept infringement upon individual privacy and agree to release personal information? Answering these questions may shed light on why the general public would be likely to comply with the government regarding privacy policy.

Fukuyama (2020a) called the pandemic a global political stress test. This test is still ongoing and taking different measures and forms in different countries. In the following sections, this study will present Taiwan as a case attempting to balance the tradeoffs between public health against democracy and collective security against individual privacy. The first section introduces the so-called “Taiwan model” and the privacy concerns of social surveillance. Next, we review the possible conflicts between democratic values, collective safety, and individual privacy. This study then proposes two sets of hypotheses regarding value conflicts and privacy policy debates. We use data from a survey conducted in May 2020 to test these hypotheses. The data shows that during the pandemic, a vast majority of Taiwanese people prioritized collective security over individual privacy; meanwhile, a stronger democratic value also came to the forefront. This study will analyze how people attend simultaneously to these seemingly conflicting values in the policy of revealing individual information.

Why Taiwan?

The “Taiwan model” was dubbed for its so-far successful record combating COVID-19 and exclusion from the World Health Organization (WHO) (Taiwan News, 2020; Yip, 2020). With a population of 23.8 million, Taiwan has recorded 476 confirmed cases and seven deaths as of August 5. No lockdown has been implemented; schools, offices, shops, and public places all remain open. The Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) is a key part of Taiwan’s success story. Learning from experience from SARS in 2003, the CECC coordinates cooperation across many government ministries and agencies. CECC also promptly makes many decisions, ranging from border control by banning travel and visitors, mask manufacturing and supply-rationing systems, quarantines and contact-tracing, and detailed surveillance of infected people.

To limit the spread of the coronavirus for the past few months, severe measures, such as quarantines and intensive monitoring, which might invade individual privacy were taken in Taiwan. Baldwin (2005) distinguished between “voluntarist strategies” (education and voluntary behavioral change) and “harsh interventions” (quarantine, social surveillance, centralized forcible treatments), among which the former tends to respect human agency and the latter tends to raise the conflict between individual liberty and the collective good. The possible consequences of whether revealing personal information of quarantined people could help manage the pandemic or make more people avoid testing have been heatedly debated in Taiwan.

In comparison, Taiwan has been considered an example of applying a centralized digital tracing approach. Unlike a decentralized user-centric approach that relies on individual responsibility, in Taiwan, smartphone location tracking has been used by the government to detect and sanction quarantine violations (Cohen et al., 2020). The DW (The Deutsche Welle) argued that Taiwanese people prioritizing the collective over the individual makes people more willing to comply with the government’s centralized and stringent policies (Yang, 2020). Somehow with different emphases, the Guardian reported that Taiwan relies on “a completely transparent form of supervised self-discipline……Taiwan has demanded more monitoring and compliance of its people, but the result is a healthier population, greater certainty, and ultimately more liberty” (Liu & Bos, 2020). In a similar vein, Lanier and Weyl (2020) claimed that the Taiwan model “based on an ethos of broad digital participation and community-driven tool development, was fast, precise, and democratic.” The Diplomat also granted that “Taiwan is living proof that control of an emerging virus can be achieved through science, technology, and democratic governance” (Chiou, 2020).

These above observations seem to paint two contradicting pictures of Taiwan: one as a centralized digital-tracing country which is more likely to “trade-in” individual privacy for public safety, the other as an exemplary case striking a “balance” between these two ends. Using revealing individual information of infected people as a critical test, we examined whether it is possible that the so-called centralized digital tracing in Taiwan strikes a balance between individual privacy and collective security.

Privacy, Democracy, and Collective Safety

In public health, it was claimed that “we can’t do anything without surveillance . . .that’s where public health begins” (Porter & O’Hara, 2001; quoted from Fairchild et al., 2008). Social surveillance takes on various forms. In Taiwan, the debate concerning whether to publicize the personal information of infected persons to prevent the spread of the virus poses the democratic dilemma between public health and civil liberties. The inevitable harsh intervention raises a series of questions regarding the possible trade-offs between democratic values, public safety, individual liberty, and privacy.

First, will the democratic government be willing to employ strong interventions like social surveillance, which might restrict or violate individual privacy? Many discussions consider the battle against COVID-19 as a performance competition between the democratic and authoritarian governments. Because of the responsibility structure, democratically accountable leaders have strong incentives to improve public health (Besley & Kudamatsu, 2006; Bollyky et al., 2019), taking stringent measures to avoid blame and electoral punishment (Cronert, 2020). In contrast, a democratic government enduring lengthy public deliberation and scrutiny might also lead to policy gridlock, particularly in taking actions that might restrict individual freedom.

The majority of democratic citizens are supposed to support civil rights and liberties. However, Sullivan and Hendriks (2009) argued that the events of 9/11 have reshaped citizens’ relationship with their government in terms of the trade-offs they are being asked to make between security and liberty. After the 9/11 attacks, the threat perceptions have reduced the differences in preferences between nonauthoritarians and authoritarians (Hetherington & Weiler, 2009). Ordinary, democratic citizens who feel their safety is threatened will be more likely to support anti-democratic policies to ensure public safety (Hetherington & Suhay, 2011).

The empirical evidence on the association between the democratic government and harsh interventions that might restrict individual freedom during the pandemic is still incomplete and inconclusive. Cronert (2020) found that democratic countries tended to implement school closures more quickly than authoritarian countries, while countries with high government effectiveness tended to take longer than those with less effective state apparatuses. Frey et al. (2020) found that autocratic regimes imposed more stringent lockdowns; however, collectivist and democratic countries have been more effective in reducing travel.

Conversely speaking, stringent measures taken by the government might strengthen or weaken democratic values. The findings of Amat et al. (2020) in Spain show that the COVID-19 crisis might increase the citizens’ demand for strong leaders at the expense of eroding preferences for democratic governance. Nevertheless, evidence also shows a pattern of “rally-'round-the-flag,” indicating that the pandemic crisis could lead to a surge in citizens’ approval of the democratic government in several countries (The Economist, 2020). Stringent policies such as lockdowns might lead to higher trust in and support for the democratic government in Canada (Harell, 2020; Merkley et al., 2020) and several European countries (Bol et al., 2020). There is not necessarily a trade-off between democratic values and taking effective measures against the virus.

Second, even if there is not necessarily a trade-off between democratic values and harsh interventions against viruses, would pursuing collective security inevitably risk infringing on individual privacy? Yang (2020) argued that public acceptance and compliance with the stringent measures taken by the Taiwanese government was because of the cultural legacy of Taiwanese people prioritizing the collective over the individual. Frey et al. (2020) argued that Western Europeans and North Americans are considered to be individualistic and independent. In contrast, East Asian countries are considered to emphasize the value of obedience and conformity. Their empirical findings also support that individualistic cultural traits are associated with negative attitudes towards government interventions (Frey et al., 2020).

Brzechczyn (2020) further contrasted individualistic west Europe and collectivist east Asia by separating these two groups into the regime division of liberal democracies and illiberal democracies, of which Taiwan was included in the latter group. In this distinction, liberal democracies prioritize individual rights over communal interests, whereas illiberal democracies emphasize communality and subjugate individual rights to the public interest. In the situation of threats, the government of illiberal democracies – which tend to grant the executive branch more power – enjoys higher “regulative credits” to introduce extraordinary measures and policy tools with public support. However, the concept of illiberal democracy denotes a regime classification covering many features that should not be reduced to the collectivist culture. Besides, Taiwan has long been considered a liberal democracy by global standards. All countries, regardless of their regime type, have adopted some stringent measures in combating the virus, which does not necessarily make them an illiberal regime. The real question is not whether, but to what extent is a country willing to compromise individual privacy to pursue collective security.

Furthermore, Fukuyama (2020a, 2020b) argues that the crucial determinant in effective crisis response is not the type of regime, but trust and state capacity. The divide between democracies and autocracies or illiberal and liberal democracies could be a false dichotomy. Liberal democracies might have weak governments, and autocracies might well survive the pandemic. In dealing with the crisis, all political systems need to delegate discretionary authority to the executive. What matters is whether citizens trust their governments and whether their leaders can make the best judgments (Fukuyama, 2020a, 2020b). Since 9/11, political trust, which was previously understudied, has attracted more attention. Under conditions of heightened threats, all citizens are being asked to forego some liberties, yet the extent to which citizens agree to the government curbing civil liberties depends on their trust in the government (Davis & Silver, 2004). In other health crises (such as the Ebola Virus Disease, EVD), empirical evidence has shown that trust affects people’s willingness to accept and comply with public health policies (Blair et al., 2017; Vinck et al., 2019).

Indeed, similar concerns were raised by Taiwanese legal scholars (Lin et al., 2020) regarding delegating authority to health experts and executive branches and that the growing, regulative powers might entrench an “administrative state” in this young democracy. The dilemma exists between the government’s effective interventions to safeguard public security and possible harm done to fundamental human rights and individuals’ privacy. In rigorously reviewing the legal frameworks and possible setbacks in Taiwan’s case, Lin et al. (2020) still considered that Taiwan had built open and responsive channels for information communication to address public inquiries and criticisms, which helped the government build public trust when imposing restrictive measures.

In combating the pandemic, anxieties over the possible trade-offs between “democracy vs. efficacy” and “collective security vs. individual privacy” have kept resurfacing. Next, we use the debate in Taiwan about revealing individual information of infected people to examine whether it might be possible to respond to the pandemic effectively and democratically, and the possible trade-off or balance between these seemingly conflicting values in Taiwan.

Hypotheses

Based on the above discussion, this study proposes two sets of hypotheses: first, on value conflict, second on the specific privacy policy. The first set of hypotheses concerns the possible balance between the assumedly conflicting values. The focus is to explain the increasing emphasis on collective security over individual privacy and liberty during the pandemic crisis. In the choice between public safety and personal liberty and privacy, we assume that the support of democracy is in accord with upholding personal liberty and liberty; in contrast, people with high social or political trust might rally behind the value of public safety in a crisis. Social trust between citizens helps to build cooperative social relations in a bottom-up process. Political trust between citizens and government facilitates effective government (Newton, 2001). Trust provides social bonds or collective identification, making people willing to comply with the government’s demands for the common good even if it goes against their self-interest (Levi & Stoker, 2000). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1. People with strong democratic values tend to prefer individual privacy/civil liberties to collective security.

H2. People having higher social trust tend to favor collective security over individual privacy/civil liberties.

H3. People having higher political trust tend to favor collective security over individual privacy/civil liberties.

The second set of hypotheses concerns the policy debate over releasing the personal information of patients. When the debate arose in Taiwan, some agreed to release information to prevent the virus’s spread, while others opposed it, considering it a violation of individual privacy. However, in the crisis, not releasing information might also be considered restricting a citizen’s right to information, a human right guaranteed by several international treaties (Földes, 2020). As such, those concerned with individual liberty also argue that people have the right to know, and the government has the responsibility to be as transparent as possible to aid individuals in making informed choices. The government also argues that revealing individual information will not be beneficial to public safety. Liu and Bos (2020) argued that Taiwan’s democratic government makes use of personal information appropriately by keeping up with the values of both transparency and confidentiality. The vast informed majority are willing to comply with government regulations, as long as confidentiality is kept and personal data is not revealed to the public. It implies that pursuing both democratic values and collective security could work in tandem with protecting individual privacy by not yielding in revealing personal information. More specifically, we hypothesize that:

H4. People with strong democratic values tend not to agree that releasing information of infected people is conducive to preventing the virus from spreading.

H5. People prioritizing collective security over individual privacy tend not to agree that releasing information of infected people is conducive to prevent the virus from spreading.

Data and Variables

Since 2011, the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD) has funded a telephone survey on democratic values every year except 2013 and 2017. In 2020, the foundation commissioned the Election Study Center of National Chengchi University (ESC-NCCU) to conduct the annual survey from May 6 to May 10, the primary dataset utilized in this study. This survey includes landline and cellular phone samples. Samples for landline phone interviews are randomly drawn from household telephone books. They are stratified in proportion to the size of landline telephone numbers of each county/city except Penghu, Kinmen, and Mazu. Interviewers contacted 4,460 people and successfully completed 821 interviews. Samples for cellular phone interviews are generated based on the prefixes provided by the National Communication Council. There are 405 completions out of 1,132 contacts. To make sure that all of the 1,226 samples are representative of the population, observations are weighted by gender, age, education, and residential area.

The first of our two dependent variables is collective security. We measure it by asking respondents, “Keeping society safe may infringe on personal liberty and privacy. Which is more important to you: Public safety or personal liberty and privacy?” Regarding the second dependent variable, releasing information of infected people, we ask respondents if they agree that “people have a right to know so the government should release personal information and home addresses of confirmed cases to avoid more infection.”

We used some independent variables to predict the two dependent variables, including democratic value, social trust, political trust, and partisanship. Frey et al. (2020) show that contact tracing is a function of autocratic regimes; countries that have civil and political rights seem to implement less stringent lockdowns and contact tracing. We assume that people who support democracy tend to emphasize individual liberty over collective security, even in the face of a health crisis (H1). We gauge respondents’ democratic values by asking them if they agree that “democracy may have its problems, but it is the best system of government.” We also weigh respondents’ social and political trust. Social trust represents a belief in the kindness and reliability of others (Newton, 2001). We expect that it would predict positive opinions on collective security (H2). Social trust is measured by the question: “To what extent do you agree that most people in our society can be trusted?” Political trust is about citizens’ confidence in political institutions and leaders (Hetherington, 1998). We measure political trust with this question: “To what extent do you agree that what the government does is mostly right?” We expect that political trust is linked to support for the government’s privacy policy (H3).

Some sociological and psychological variables may influence the dependent variables, so we include them to avoid the overestimation of the independent variables’ effect. In addition to gender, age, and education, we also control party identification with “Pan-Green,” “Pan-Blue,” and others. Some studies found that the people’s response to the coronavirus is structured by partisanship (Cornelson & Miloucheva, 2020; Gadarian et al., 2020; Grossman et al., 2020). In Taiwan, people who lean toward the KMT (Kuomintang), PFP (People’s First Party), and NP (New Party), each of which has long upheld the value of authoritarianism, are categorized as “Pan-Blue.” People who identify with the DPP (Democratic Progressive Party) and NPP (New Power Party) are grouped into the “Pan-Green.” The rest are grouped into “others”, including the TPP (Taiwan People’s Party), established in 2019, whose party identification has not yet been firmly established among voters. We assume that people of Pan-Green tend to support whichever policy the current government has implemented. When the current Taiwanese government suggests collective security and withholds releasing personal information, Pan-Green will support them both, and vice versa.

Because our outcome variable has a Bernoulli distribution with parameter p, we can use the inverse normal link function to transform the expectation of 0/1 dependent variable:

Pr(Y=1|X)=Φ(βkXik)

where the symbol Φ is the cumulative standard distribution, and X is a vector of independent variables. The linear combination of the covariates and unknown parameters, β, is used to calculate the predicted probabilities. After using the IRLS algorithm to estimate the parameters, coefficients can be interpreted as the difference in Z score associated with each one-unit difference in the predictor variable.

Results

Explaining Values of Collective Security vs. Individual Privacy

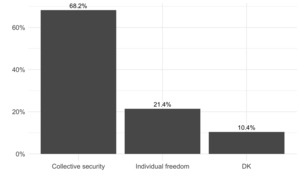

Before exploring the determinants of collective security and privacy policy, this study begins with a description of these two variables. Figure 1 shows that an absolute majority of the respondents (68.2%) value “public safety” more than “individual privacy or freedom;” only 21.4% of respondents think the other way. It indicates that collectivism is relatively strong in Taiwan; people could trade their civil liberty for the safety of society. At first glance, this result seems to confirm Brzechczyn’s (2020) observation that collectivist Taiwan prioritizes communality over individual rights.

Nevertheless, Taiwan has long been ranked by Freedom House as a free democracy that values individual rights.[1] During the pandemic crisis, Taiwan has also reached the highest score of supporting democratic value compared to previous years. About 79.7% of respondents agree that “democracy may have its problems, but it is the best system of government,” the highest percentage in the past ten years. The pursuit of collective security grows with the support of democratic values at the same time. The more apt question should be under what conditions Taiwanese people are willing to yield in their civil liberties in exchange for collective security during a crisis.

H1-H3 Results

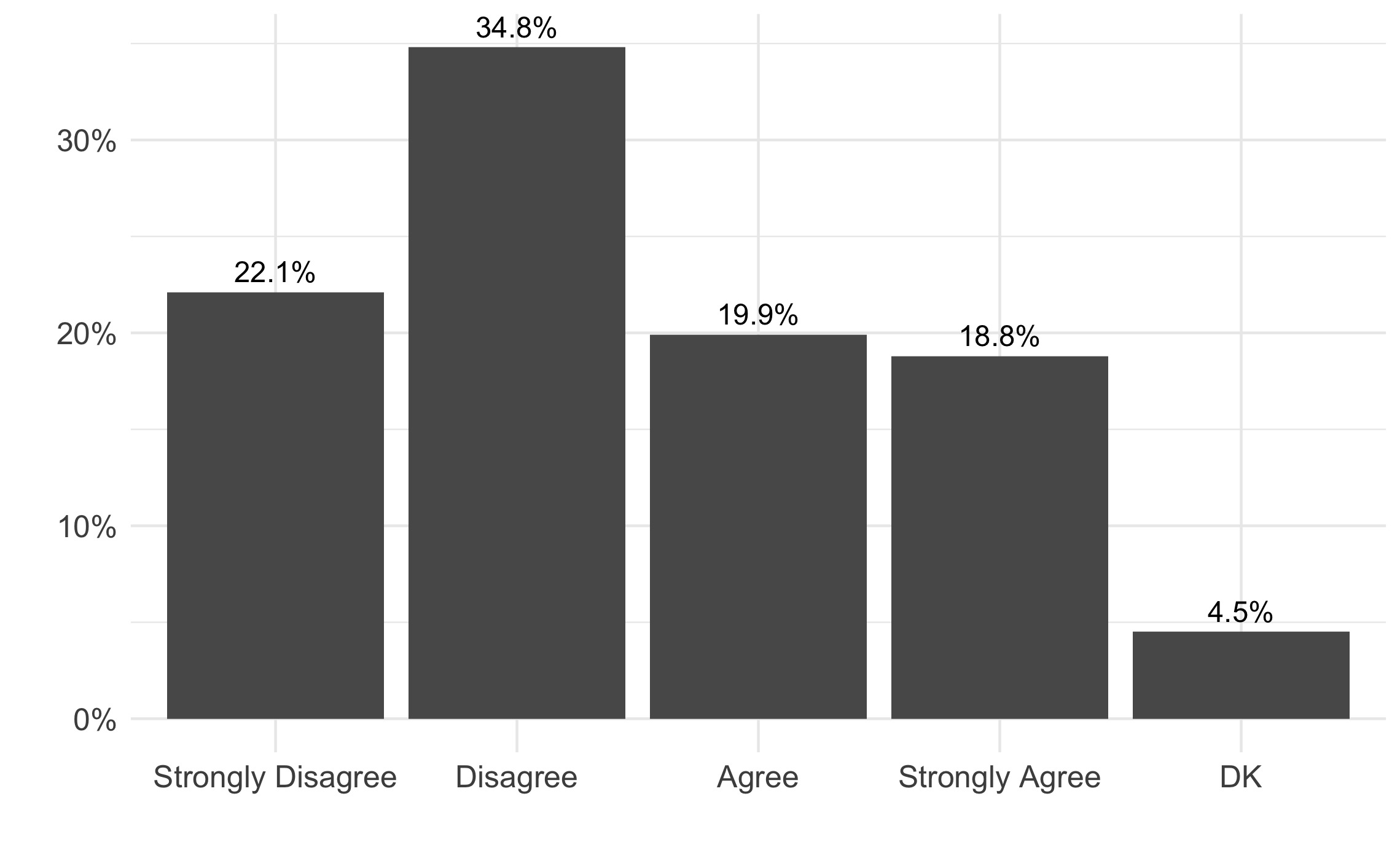

Table 1 shows the estimates and summary of the probit regression model of collective security. Among the three value variables in the model, social trust is a significant predictor. As social trust increases by one unit, the cumulative density (Φ(Xβ)) increases by 0.106. Figure 2 shows the increasing predicted probabilities conditional on social trust. The difference between each level is around 0.03. This result confirms H2; people with higher social trust tend to value public interests rather than civil liberty. However, H1 and H3 are not supported; the chances that democratic values and political trust are not related to collective security are quite large statistically. Our findings imply that collective security comes from trust in other people, rather than support for democracy, political trust, or political identity. Taiwanese people’s sense of public trust is bottom-up instead of top-down.

With the exception of social trust and age, all of the other covariates are not significant statistically. In that case, the more pressing question would be whether people’s prioritizing collective security over civil liberties could jeopardize individual privacy. This is what we examine next.

Explaining the Privacy Policy on Releasing Personal Information or Not

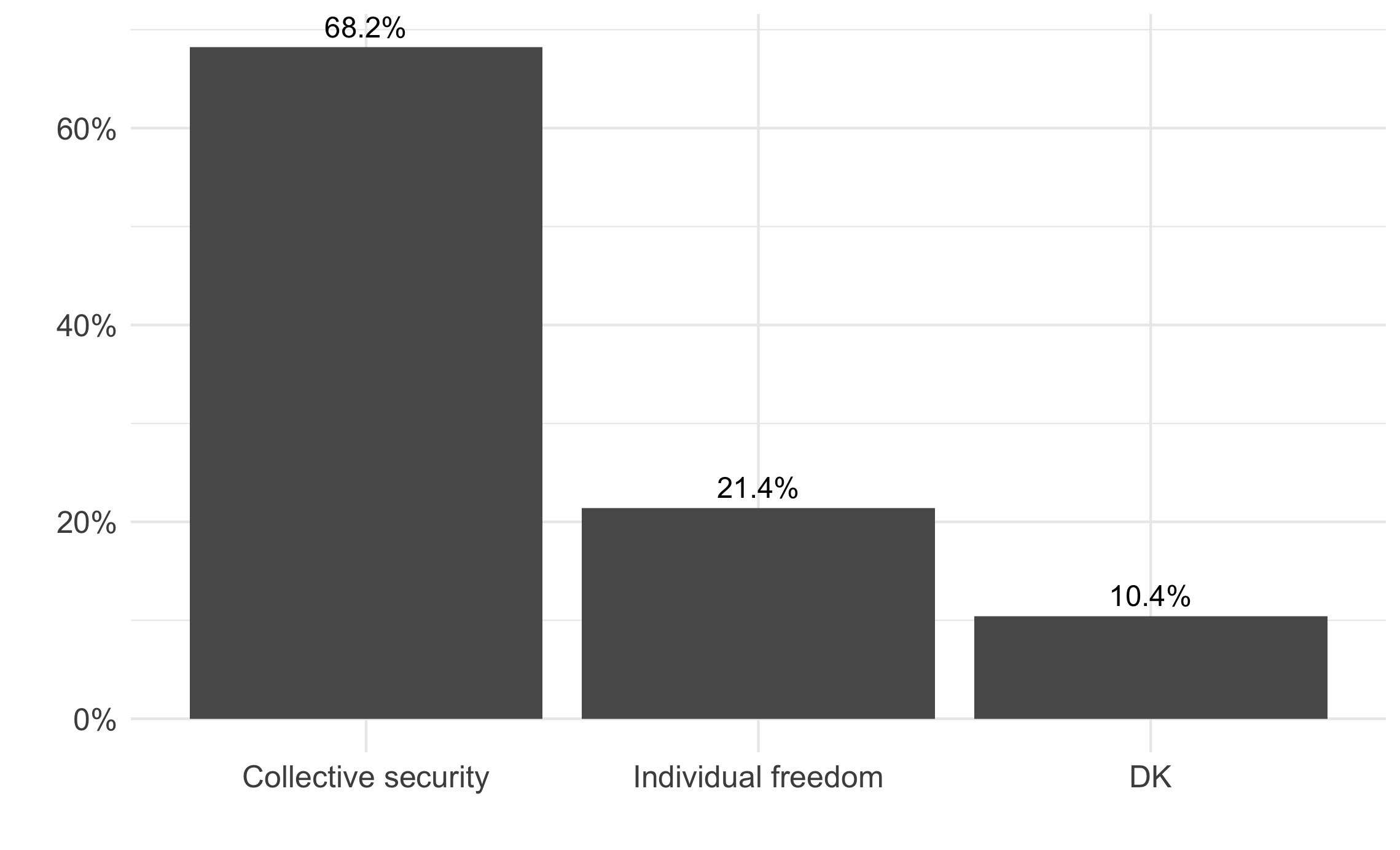

Figure 3 displays a similar pattern as Figure 1. Regarding whether the government should keep people informed and release private information and home addresses of confirmed cases, 56.9% (22.1+34.8) of respondents disagree with this statement, while 38.7% (19.9+18.8) of respondents support this idea. Although most people oppose releasing information of infected people, different responses to the government’s handling of such information deserves further investigation.

H4 and H5 Results

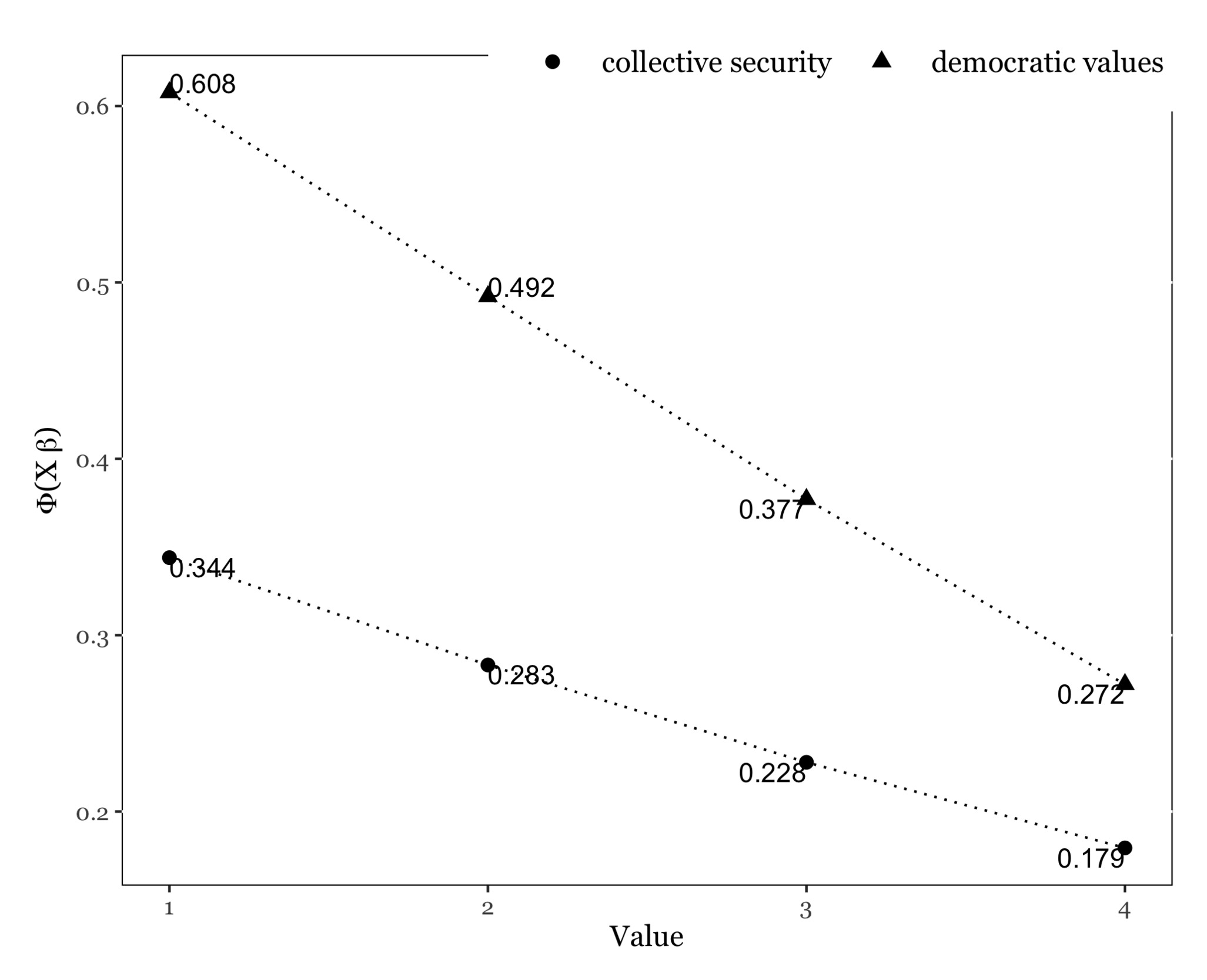

Table 2 shows the summary of the probit regression model of releasing information of the infected people. For a one-unit increase in democratic values, the cumulative density decreases by 0.293. This result confirms H4; people with democratic values tend not to agree with releasing individual information of infected people; democratic values function as a guardian of personal privacy. During the pandemic, “rally-'round-the-flag” may increase people’s confidence in the democratic government, and this sentiment will not trade in individual privacy. In addition to democratic values, people’s concern about collective security also affects the attitude towards releasing information. For a one-unit increase in the value of collective security, the cumulate density decreases by 0.171. This result confirms H5, that collective security could ensure personal privacy even though some people use transparency to justify revealing information about infected people. As the Ministry of Health called for respect for privacy and insisted that releasing information can only lead to a “witch hunt,” a sense of common good is manifested during this difficult time. In addition, education is negatively related to releasing information, but Pan-Blue identification increases the probability of favoring releasing information.

Based on the estimates in Table 2, we calculate the changes in predicted probabilities due to change in democratic values and collective security and demonstrate the results in Figure 4. The magnitude of change in favoring releasing information is about 0.1 for different levels of democratic values and 0.06 for collective security. It is obvious that democratic values along with collective security and education are negatively correlated with releasing information of those with confirmed cases.

Conclusion

The existing literature on the public support for civil liberties has noted that people who perceive threats are more likely to support anti-democratic policies to ensure public safety (Hetherington & Suhay, 2011). Goldenfein et al. (2020) argued instead that privacy versus safety is a false trade-off. With regard to digital tracing, we can have democratic data if public health authorities are held democratically accountable and ensure the rigorous legal protection of privacy and shield data from extraction. It’s possible to achieve public health without illicit surveillance. In Taiwan, we see the possible coexistence of protecting individual privacy and public health. This study is an attempt to explain how the possible balance of these seemingly conflicting values is achieved.

During the pandemic crisis, the increasing concern for public safety has coincided with the rising support for democratic values. The rally-‘round-the-flag effect has manifested in the Taiwanese government’s high approval rating in combating the virus and has reinforced people’s belief in democratic values. Meanwhile, citizens’ increasing support for democratic values has no direct effect on their choice between civil liberties and public safety. The majority of people, 68.2%, are willing to trade their civil liberties and privacy for public safety. Existing research contended that citizens’ trust in government affects their willingness to give up civil liberties in exchange for security under the condition of threats (Davis & Silver, 2004; Sullivan & Hendriks, 2009). Trust did account for citizens’ value choice, as we found in Taiwan. However, it is social trust, not political trust, that makes people willing to give up their civil liberties in exchange for public safety. The increasing collectivist spirit was mainly formed on a bottom-up basis.

The prioritization of collective safety over civil liberties raises the concern of possible violations of individual privacy. In practical terms, we also examine people’s attitudes towards the controversial policy of releasing infected people’s information to protect public safety. The Taiwanese government claimed that over-intensive surveillance releasing individual information stigmatizes infected people, which is not conducive to public security. This framing implies that infringing individual privacy will not ensure collective safety. Our models show that those who prioritize collective security over civil liberties tend to oppose releasing individual information, which is consistent with the government’s claims.

It is particularly interesting that strong democratic values, which did not deter people from prioritizing collective safety over civil liberty, did serve as a guardian against privacy infringement. We found that people who support democratic values and pursue collective security tend to avoid violating privacy by opposing the release of personal information. This study proves that democratic values do not necessarily hinder collective safety, and the pursuit of collective safety need not necessarily sacrifice personal privacy. As a constitutional democracy, Taiwan stresses the rule of law and social solidarity; both the government and the general public choose to pursue collective safety while protecting individual privacy. Thus far, this approach seems feasible and workable.

Biographical Notes

Wan-ying Yang is in the political science department at National Chengchi University and can be reached at National Chengchi University, No. 64 Section 2, Zhinan Road, Wenshan District, Taipei City, Taiwan 116 or by e-mail at ywy5166@gmail.com.

Chia-hung Tsai is affiliated with the Election Study Center and Taiwan Institute of Governance and Communication Research at National Chengchi University. Dr. Tsai can be reached at National Chengchi University, No. 64 Section 2, Zhinan Road, Wenshan District, Taipei City, Taiwan or by e-mail at tsaich@nccu.edu.tw.

Correspondence

All correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Wan-ying Yang at National Chengchi University, No. 64 Section 2, Zhinan Road, Wenshan District, Taipei City, Taiwan 116 or by e-mail at ywy5166@gmail.com.

Date of Submission: 2020-06-30

Date of the Review Result: 2020-07-05

Date of the Decision: 2020-07-15

For Taiwan’s freedom ranking and democratic status over the past 30 years, please check the Freedom House website https://freedomhouse.org