With its growing economic, political, and military power, China is increasingly viewed by many developing countries as a model for improvement (Stephen, 2021, 2024). However, its foreign policy during the Xi Jinping era has intensified perceived threats to U.S. interests (He, 2017; Thompson, 2020). This situation can lead to uncertainty, instability, and even conflict in the global order (Christensen, 2015). International relations have become increasingly complex, especially with the progress of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the COVID-19 pandemic (Beeson, 2018). The BRI, launched by China in 2013, is a global infrastructure and economic development strategy aimed at enhancing connectivity and trade through large-scale investments in transport, energy, and digital networks across Asia, Africa, and Europe (Zhao, 2019). Concerns about China’s global ambitions are growing, particularly in the context of escalating trade tensions and competition in areas such as technology and geopolitics between the U.S. and China (Boylan et al., 2021; Kotz & Yang, 2022). These fears have raised the specter of ongoing rivalry and potential conflicts in multiple domains.

In order to mitigate or even eliminate other countries’ perceptions of a “Chinese threat,” China has been practicing a new public diplomacy strategy (Nye, 2023; Voon & Xu, 2020). National image is an important manifestation of soft power (Nye, 2022), which involves not only a country’s perception of itself, but also the perception of other actors in the international system (Boulding, 1959). Therefore, an essential goal of China’s public diplomacy is to encourage the international community to actively participate in its diplomatic initiatives (Wang, 2008).

In this context, Chinese New Year speeches (CNYSs) play an important role (Wu et al., 2021). These speeches become a platform for China to present its self-image to the world, as they are widely distributed on global social platforms such as YouTube by the China Global Television Network (CGTN) (Zhu, 2022). Understanding the intentions behind China’s diplomatic discourse through CNYSs, and how these messages are communicated to both domestic and international audiences, is essential.

To thoroughly examine the linguistic strategies and identify intentions in CNYSs, critical discourse analysis (CDA) and systemic functional linguistics (SFL) offer powerful analytical frameworks. CDA holds that language is a product of social processes (Fowler, 2013), revealing the power and ideology embedded within discourse (Fairclough, 1993). Meanwhile, SFL can provide a grammatical foundation for textual analysis (Fairclough, 1995). Complementing this approach, Halliday (1994) proposed that a process-centered theoretical framework should be established to understand human experiences through the transitivity system, which is a core theory in SFL. In other words, this grammar of process-participant configurations brings to light the underlying patterns of meaning-making in reality construction, serving as a useful analytical tool for examining how different social actors shape and represent reality in discourse (Tang, 2021). By combining CDA and transitivity theory, we can better illuminate how CNYSs use language to construct China’s image and uncover the power relations involved in this representation. Therefore, this study focuses on examining the CNYSs on CGTV from 2014 to 2023.

This study proposes the following research questions to be addressed: (1) What facets of China’s image are constructed through the transitivity process in the CNYSs? (2) How does the transitivity system in the CNYSs contribute to the representation of China’s image? (3) What are the power dynamics and ideologies shaping China’s image as represented in the CNYSs? There are two motivations for conducting this research. The first one is to enrich the growing corpus of studies on diplomatic discourse. The second is to shed some light on China’s image, providing valuable perspectives on the current complex and changing international relation landscape.

Literature Review

National Image

The term “national image” is usually considered to have been first proposed by Kenneth Boulding (1959), who introduced a social psychological perspective to the international system in the context of the Cold War. Boulding (1959) defined national image as the overall impression of a country in the international community. Holsti (1962) later expanded on this idea, considering national image as a subpart of broader belief systems held by individuals and groups. While this advancement provided a more comprehensive cognitive explanation, it still fell short of fully addressing the role of media representation.

Research on national image spans across various fields (Buhmann & Ingenhoff, 2015), with significant contributions in international relations (Pahlavi, 2007), communication sciences (Thiessen & Ingenhoff, 2011), business (Dinnie, 2022), and social psychology (Brown, 2011). Unlike previous studies, which typically treat these areas separately, this study bridges communication sciences and international relations by emphasizing the critical role of mass media and public diplomacy in the construction of national images.

As Wodak (2009) argues, national image is the product of discourse. Scholarly works have examined how political discourse (Knüsel, 2016), diplomatic discourse (Semenov & Tsvyk, 2021), and media discourse (Peng, 2004; Xiang, 2013; L. Zhang & Wu, 2017) are used as tools to construct China’s image. This study is based on a large amount of literature on Chinese diplomatic discourse, especially related to national image. Because of space limitations, the following is only a compendium of linguistic theories and methods that are particularly relevant to this study.

SFL (Halliday, 1961) and CDA (Fairclough, 1989; Van Dijk, 1984; Wodak, 1989) have been widely utilized. The former emphasizes the functionality and selectivity of language (Caffarel et al., 2004), highlighting how discourse constructs meaning according to the requirements of its social context (Li & Pan, 2021). The latter effectively reveals hidden ideologies and non-transparent power relations in discourse (Gu, 2019; Tang, 2021; L. Zhang & Wu, 2017). Simultaneously, CDA often engages indirectly with specific news events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Y. Zhang et al., 2022) and the Diaoyu islands dispute (Jin & Shang, 2015). These case studies attempt to expose underlying international interests and political control. National image is constructed and presented in the international arena through multiple linguistic resources and discursive practices. Accordingly, combining SFL and CDA highlights the importance of giving greater attention to both the contextual and critical dimensions of discourse (Martin & Wodak, 2003).

Prior diplomatic discourse research on China’s image is mainly based on qualitative methods. For example, Scott (2015) analyzed the role of China as represented in public diplomacy discourse under the leadership of Hu Jintao from a rhetorical perspective. Similarly, based on the evaluation system and the ideological square model, Li and Pan (2021) found that China was portrayed more negatively in the translated text compared to the original. Cappelletti (2019) examined China’s new identity in overseas communication through Twitter. While qualitative methods have provided valuable subjective interpretation and in-depth insights, they often focus on selective examples and limited datasets, which may not fully capture broader linguistic trends across a larger corpus of diplomatic texts.

To address these limitations and improve the reliability and replicability of the analysis, this study incorporates corpus linguistics (CL) as a useful complementary approach. Unlike qualitative methods, which typically offer detailed contextual analyses, CL allows for the systematic investigation of linguistic patterns across extensive datasets (Baker et al., 2008).

Critical Discourse Analysis

CDA is an interdisciplinary method for studying discourse, treating language as a form of social practice (Fairclough, 1989). Van Dijk (1995, p. 17) posited that “ideologies are also enacted in other forms of action and interaction, and their reproduction is often embedded in organizational and institutional contexts.” It primarily focuses on the relationships among language, ideology, and power, and the connections between discourse and social change (Fairclough, 1993). Van Dijk (2001) described CDA as discourse analysis with attitude, meaning that discourse analysts should take a personal stand and put themselves in the position of the underprivileged to expose discrimination, inequality, and power relations embedded within discourse. This, in turn, can promote social change and the realization of social equity and justice.

However, the application of CDA has also generated much controversy because it is not a directly applicable theory for studying social problems and cannot provide a ready-made path for social analysis (Wodak & Meyer, 2015). In addition, scholars have disputed the political mission, arguing that CDA is selective in its analysis of textual and linguistic characteristics, as well as strongly subjective (Chilton et al., 2010; Van Dijk, 2008).

For more than 40 years, many global scholars have combined corpus technology with CDA, especially for the emergence of corpus-based media and diplomatic discourse analysis. Hardt-Mautner (1995) first tried to combine CL and CDA in the 1990s. Later, Baker and McEnery (2005) and Baker et al. (2008) developed a framework for corpus-based CDA, which significantly standardized the analysis approach. As Mautner (2016) points out, although CL is not central to CDA methodology, its role in enhancing CDA’s analytical rigor cannot be overlooked. CL allows researchers to handle larger datasets and offers methodological triangulation, addressing the problem of subjectivity in traditional discourse analysis.

Transitivity System

SFL is usually considered the main substructure of CDA in pragmatics (M. Zhang & Pan, 2015). SFL views language as a social semiotic system, meaning that it is a tool people use to create meaning in social contexts. Within this framework, language serves three metafunctions, including the ideational, interpersonal, and textual functions (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). The ideational metafunction refers to how language represents the world, with the experiential function, a component of the ideational metafunction, specifically addressing how language construes human experience and organizes our perceptions of reality.

One of the most widely used SFL grammatical tools is transitivity, which represents the experiential function of ideational meaning (Halliday, 1994). It is described as the “linchpin of reality construction” (Hawkins, 2004, p. 30), and is recognized as a valuable tool for revealing agency, power relations, and ideologies. The transitivity system contains three main components: the process itself, participants in the process, and circumstances surrounding the process (Halliday, 1994). The transitivity processes are categorized into six types, which include three main processes, namely material, mental, and relational, as well as three complementary processes, namely behavioral, verbal, existential (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). Importantly, each process is intrinsically linked to specific participant types.

Data and Methods

Corpus Data

The text corpus consists of English-language CNYSs delivered by Chinese President Xi Jinping spanning from 2014 to 2023 for two main reasons. On the one hand, China replaced its president in 2013 and proposed the BRI in September of the same year (He, 2021). On the other hand, the exclusive focus on the English versions of these speeches aims to provide insights into how China’s image is presented in a global context (Zhu, 2022).

Moreover, the CNYSs were sourced from CGTN’s official YouTube channel, which plays a crucial role in China’s international media strategy. It is noted that the videos of CNYSs have garnered nearly 3 million views. Additionally, engagement metrics, such as the number of likes and comments, have shown a consistent upward trend over the years, indicating increasing global interest in these speeches (see Table 1).

Lastly, the total length of the corpus is 11,416 words, encompassing 498 sentences. The average word and sentence length in the corpus are 5.0 characters, and 22.9 words, respectively. In terms of lexical diversity, there are 2,585 distinct word types (unique words) and 11,570 tokens (total number of words, including repetitions) in the corpus, showcasing a rich and varied vocabulary used in the texts. The type/token ratio (TTR) was calculated to be 22%.

Analytical Approach

First, we laid the foundation by conducting a quantitative analysis using the UAM corpus tool 3, developed by Mick O’Donnell. This tool can linguistically code the corpus based on a hierarchical structure (Teich, 2009). The clausal analysis was performed automatically according to the guidelines of the transitivity system. After categorizing all the subcategories, a detailed review was conducted by two PhD students fluent in English and SFL. To test the accuracy of the analysis, the study compared the measures of the two coders by referring to the reliability calculation method proposed by Holsti (1969). As a result, the average agreement reached 0.85, and the reliability coefficient was 0.92 (greater than 0.8), which fulfills the requirements.

Second, after coding, we conducted a statistical analysis of the data using the built-in calculation functions of the UAM corpus tool 3 software. Through this process, we identified the top 30 high-frequency process terms in the CNYSs for further analysis, as shown in Table 2. After identifying recurrent transitivity system patterns, 30 terms in different forms were lemmatized into 25 lemmas. For example, work (19), worked (5), and working (8) were lemmatized into WORK (32).

Third, according to the examples of classification about transitivity grammar (see Table 3), three types of processes and five specific process categories were identified. Among them, material processes include acting (34.7%), creating (13.5%), and happening (12.9%), mental process corresponds to sensing (13.2%), and relational process corresponds to being (25.7%), as shown in Table 4. In addition, examining the prominent verb words and their contextual usage, five types of China’s image were further identified. These are “the maker” (n = 116), “the definer” (n = 86), “the creator” (n = 45), “the wisher” (n = 44), and “the achiever” (n = 43), as shown in Table 5.

Fourthly, the process terms corresponding to the five types of China’s images were indexed separately with Antconc 3.5.9. This corpus tool, developed by Laurence Anthony, provides a range of functions (e.g., wordlist, keyword, collocates, clusters, concordance) that help researchers systematically and efficiently analyze and visualize textual data (Froehlich, 2015). Notably, the concordance tool in this software allows for a detailed examination of the context in which keywords appear. After indexing the top 30 high-frequency process terms, a total of 334 concordance lines were obtained. The range of themes involved in the concordance line was judged based on their surrounding contexts as follows: social affairs (n = 152), diplomatic affairs (n = 64), political affairs (n = 62), and economic affairs (n = 56). Clarifications of these four themes are provided in Table 6.

Lastly, to assess the prominence of the four themes in relation to China’s image, all the concordance lines were organized according to the categorization of China’s image. The data was then recorded and processed through Excel, and the percentages were calculated (see Table 7).

Findings and Results

The Image Realization of “the Maker”

To begin with, China is frequently presented as “the Maker,” accounting for 34.7% of all cases, ranking first. The CNYSs use a series of process terms (make, work, live, put, held, visit) to depict China as a nation that is constantly on the move to improve its well-being.

Further vertical examinations of “what China made” indicate that the social issues are the primary focus, comprising 18% overall. The prominence of this theme is consistently represented across other images of China. Detailed concordance analysis shows that China has MAKE [made] great (historic, active, overall, countless, spectacular, important, large, outstanding, concerted, unremitting) achievements (contributions, steps, plan) on all levels (poverty alleviation, technology innovation, peace, Chinese dream). Furthermore, China consistently PUT people first (all along), encouraging them to WORK together (hard, harder, tirelessly, steadily, diligently), and LIVE in happier life (happiness, peace, harmony, better life). Chinese officials constantly VISIT[ed] impoverished counties (14 contiguous areas of dire poverty, the families of two villagers from the Yi people).

Turning to political issues, the emphasis is at 6.0%. The Chinese government has also MAKE [made] efforts to implement structural reforms (deepening reforms, judicial system, party and government discipline, the exercise of the party’s strict governance), and to fight against undesirable work styles (formalism, bureaucracy, hedonism and extravagance, corruption). It is worth noting that war metaphors appear frequently in the image of “the Maker,” according to conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). For example, phrases like “turn confrontation into cooperation,” “turn swords into ploughshares,” and “the final assault on the fortress” are used*.* Furthermore, the use of more explicit war-related terminology, such as “war of attack,” and “war of defense,” renders society as being in a situation of extreme emergency. This justifies the high priority and proactive measures taken by the Chinese government.

The prominent focus on poverty alleviation and anti-corruption efforts seeks to affirm the superiority of socialist values and advancement of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Compared to capitalism, which often prioritizes market forces and individual gain, China adheres to a people-oriented approach, actively assuming the collective responsibility and common interest inherent in socialist governance (Gore, 2019). In contrast to other political parties, the CPC exercises full and strict governance over the party and improves the party’s working style. As a result, these efforts have strengthened public trust in the country’s governance, affirming the legitimacy and capability of the government to lead the nation toward prosperity.

In addition, China’s active and pivotal role on the global stage is further emphasized by the 6.6% representation of diplomatic gatherings and the major international events it has hosted. China has HELD numerous high-level international cooperation and dialogue platforms (the Belt and Road, South-South cooperation, APEC and G20 Leaders’ Summit). Chinese leaders also have VISIT [ed] many countries (five continents, foreign leaders) and attended numerous important diplomatic events. It is evident that China has been actively leading self-centered global cooperation and dialogue.

The Image Realization of “the Definer”

“The Definer” is the second most prominent image, accounting for 25.7%. In terms of

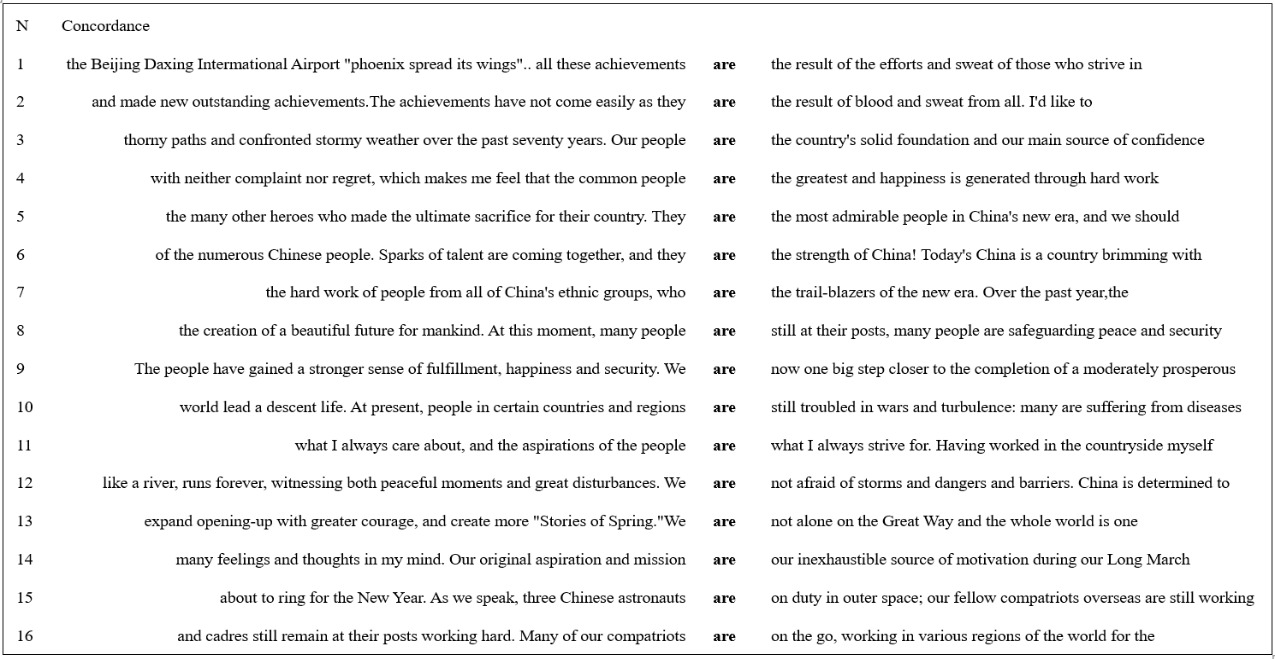

theme distribution, social issues remain the focus with 16.5%. However, unlike “the Maker,” it emphasizes the characteristics and status of the identity subject. The concordance of “are” shows a positive profile (Figure 1).

Regarding how to identify “who was defined,” the study started from carrier/attribute and identified/identifier (participant type) analysis related to the relational process. Consequently, two main categories emerged. The first group consists of the Chinese people, whose achievements and aspirations ARE the result of blood and efforts (inexhaustible source of motivation) (concordance 1, 2, 11, 14). In this process, the common people ARE not afraid of storms and dangers (still at their posts, not alone on the Great Way, on duty in outer space, on the go) (concordance 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16). Furthermore, they are portrayed as the greatest (most admirable) people (concordance 4, 5) and the driving force (strength, foundation, source of confidence, trail-blazers) behind China’s development (concordance 3, 6, 7, 9). These emotional descriptors not only praise the people but also embed a collectivist ideology that underscores the close alignment between individual actions and national goals. Consider the extended context of concordance line 3 as an example.

Through the years [time], the Chinese people [carrier, actor] have been [relational process] self-reliant [attribute] and worked [material process] diligently to create [material process] Chinese miracles [goal, phenomenon] that the world [sensor] has marveled at [mental process]. Our people [carrier] are [relational process] the country’s solid foundation [attribute] and our main source of confidence to govern [attribute].

Following the appraisal framework proposed by Martin and White (2005), the Chinese people are positively judged as “self-reliant” and “diligent.” This implies the quality of not being dependent on foreign aid and having the ability to succeed on their own. In addition, the people are referred to as the “country’s solid foundation” and “main source of confidence to govern.” In fact, a reciprocal relationship between China and its people is being actively constructed. By integrating the image of the people into the nation’s success story, the Chinese government not only strengthens domestic political cohesion but also transforms national pride into a shared asset, further enhancing the collective patriotism.

The second group is identified as China. Frequently, statements assert that "today’s China IS a country brimming with vigor and vitality (where dreams become reality, that keeps to its national character, that draws its strength from unity), and that “China IS linked with the world (the first major economy worldwide).” These statements reflect China’s internal self-identity while also maintaining its national character. This suggests to the global audience that China is resilient and capable of setting an example for other countries.

Moreover, the frequent use of family metaphors suggests a cultural and ideological connection between China’s domestic values and its foreign relations. For example, expressions like “the whole world is one family” and “the world is one big family” are used to map familial kinship to China’s relationship with other countries, thereby fostering a sense of psychological closeness and creating a more intimate atmosphere. This mirrors traditional Confucianism in the Chinese mind, emphasizing familial bonds and benevolence as core values that promote social harmony. By invoking these cultural values, China projects its domestic governance ideals onto the international arena, subtly promoting its worldview and diplomatic model. This rhetorical strategy serves as a form of cultural diplomacy, providing valuable opportunities to enhance international empathy and trust (Brautigam, 2020). This approach enables China to navigate the complexities of global politics more effectively and to reduce tensions arising from ideological differences.

“The Creator,” “the Wisher” and “the Achiever”

The images of “the Creator,” “the Wisher” and “the Achiever” are comparatively less prominent, at 13.5%, 13.2% and 12.9%, respectively. Each image emphasizes different themes, collectively contributing to the multidimensionality of China’s image.

First, the realization of “the Creator” is most prominently reflected in economic affairs, which accounts for 5.4% of the speeches overall. This is particularly evident in regional development and technological innovation, highlighting that “high-quality development” has become a national strategy. Regarding the regional coordinated development, China actively PUSH[ed] collaboration among various regions (e.g. the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, the Yangtze River Economic Belt, and the Yangtze River Delta). This reflects China’s control and planning over local development rather than being market-driven. Meanwhile, technological milestones (the “Mozi” quantum satellite, the Chang’e-4 lunar probe, the Long March-5 Y3 rocket, the C919) that were LAUNCH[ed] have been highlighted.

These accomplishments signify the ongoing shift from “Made in China” to “Created in China,” indicating China’s evolving role in the global supply chain. Instead, it is pursuing an innovation-driven economic model to showcase the economic strength of its socialist system and future growth potential (Tekdal, 2018). This is because it helps to enhance the country’s international reputation and attract foreign investment (Fan & Hao, 2020; Jahanger, 2021). However, it is worth considering that while such narratives emphasize successes, they may not adequately address existing economic challenges, such as the recession in the real estate market (Chen, 2023). This focus may provide short-term reassurance, but it could also lead to questions about economic transparency and the long-term situation.

Second, the most prominent themes associated with “the Wisher” are social and diplomatic matters, each representing 4.8% of the total, while economic affairs and political affairs account for 2.1% and 1.5%, respectively. Regarding social affairs, China’s primary focus is on making a commitment to the people. The first thing is to REMEMBER the admirable individuals (those still living in hardships, the sacrifice and contribution of those who gave their lives), and MAY our people live in peace and harmony (the deceased rest in peace, the living remain safe and sound). The second focus is to ENSURE the safety (peace, food supply, a better life) of people and striving for the country to ENJOY prosperity (a better tomorrow, peace and happiness). On diplomatic matters, President Xi prefers to WISH the entire population (Hong Kong, compatriots, friends from all countries, international community) a prosperous (peaceful, smooth, thriving, harmonious) New Year. He also HOPE[s] that people of all countries (all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation, compatriots on both sides of the Strait) can join forces (make concerted effort, understand and help each other).

Unlike the American dream, which emphasizes freedom across all classes (Cullen, 2003), “the Wisher” places a strong emphasis on “peace.” This demonstrates China’s public diplomacy aimed at enhancing the well-being of its diverse population while also promoting harmonious international relationships (Hartig, 2016). This indicates that, while challenging the US-led Western order, China strives to alleviate global concerns about the tensions that its rise might create.

Third, “the Achiever” is mainly represented in political issues, accounting for 6.1% of the total. To REALIZE the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (the Chinese dream, the first centenary goal), the Chinese government is committed to continuous efforts and CONTINUE[s] to deepen (advocate, push forward, improve, strive) the reform (Party and government’s working style). That is further reinforced by China’s ongoing implementation of the “one country, two systems” framework. By shaping this shared, long-term historical mission, the government demonstrates its ambition for the country’s future development.

Additionally, social affairs account for 3.9%, while economic and diplomatic affairs represent 1.8% and 1.2%. China always KEEP[s] its goal and implementation together (feet on the ground, mission a long-term perspective). In this regard, many significant breakthroughs (a higher degree of impartiality and justice in society, task of lifting another 10 million rural residents out of poverty, decisive success in eradicating extreme poverty) have been ACHIEVE[d]. Furthermore, China actively PROMOTE[s] common development (national development, social fairness and justice). Among these efforts, the rural revitalization policy, introduced in 2017, is viewed by Liu et al. (2020) as a crucial pathway to achieving common prosperity by reducing the urban-rural gap. In essence, this policy addresses and critiques the wealth inequality that often arises from capitalist development models. Through this framework, the Chinese government seeks to strengthen social support and consolidate its governance foundation.

Discussion

Although the expression of blessings is an indispensable function of the CNYSs, the image of “the Wisher” constitutes only a small proportion, at just 13.2%. In contrast, the images of “the Maker” and “the Definer” dominate the discourse, accounting for 60.4%. This disparity suggests that the CNYSs are not merely intended to convey goodwill, but also serve as a platform to showcase China’s power. From the perspective of national image construction, the Chinese government is positioned as the central protagonist in public discourse. Whether through “the Maker,” which highlights the achievements of national development, or “the Definer,” which builds a close connection between the people and the state, the underlying emphasis remains on the legitimacy and authority of the CPC. This conveys a broader message: China’s development model is successful, bringing not only economic prosperity but also social stability and increased global influence. Nevertheless, does this narrative purely deliver blessings, or does it harbor potential threats?

For the Chinese domestic population and overseas Chinese diaspora, this is undoubtedly a blessing. By reviewing the past achievements and outlining future aspirations, China’s soft power is on full display. Meanwhile, the synchronized viewing of the CNYSs on New Year’s Eve can be seen as an interactive ritual of emotional sharing. Collins (2004) argues that interactive rituals can enhance group cohesion through shared emotional experiences. Leveraging this globally synchronized public ritual, the CNYSs not only strengthen domestic citizens’ identification with the state but also further unite the global Chinese community, encompassing Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and the overseas Chinese population. In this way, the speeches serve as emotional reassurances and calculated diplomatic efforts aimed at enhancing national identity, and ensuring sustained international support for China’s trajectory (Wu et al., 2021).

Beyond that, according to agenda-setting theory (McCombs & Shaw, 1972), mass media may not directly determine public opinion on specific events but can influence the topics that garner public attention. Since 2014, the CNYSs have referenced the BRI almost annually, appearing eight times, effectively framing it as a core component of national development and conveying the promise of shared prosperity. Countries involved in the BRI benefit from China’s economic assistance and infrastructure investments (Huang, 2016). However, despite these seemingly benevolent offerings, some countries are increasingly concerned about becoming overly reliant on China, especially regarding sovereignty and economic policy autonomy. Critics have even accused China of engaging in “debt-trap diplomacy,” suggesting this might pose a long-term threat (Himmer & Rod, 2022).

This perceived potential threat extends beyond the economic issues to include military concerns. Based on security dilemma theory, when a country increases its military capabilities to safeguard its security, other nations may interpret this as a threat, prompting them to adopt defensive measures in response (Herz, 2003). In the context of the South China Sea, countries such as Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia may view China’s rhetoric regarding national rise and sovereignty protection as a potential military threat. These nations might even perceive China’s international cooperation efforts as strategies to reshape the regional order in the Asia-Pacific, potentially undermining the autonomy and interests of neighboring states. In response, these countries could increase their military deployments or seek external support.

To mitigate geopolitical conflict, the Chinese government emphasizes “peace” and “building a community with a shared future for mankind” through the CNYSs. However, these visions sharply contrast with the US-led Indo-Pacific strategy, which may be perceived as a competing institutional framework (Saeed, 2017). As power transition theory suggests, when the political, military, and economic power of an emerging great power approaches or surpasses that of the current hegemonic power, the likelihood of conflict increases (Organski, 1958). For Western countries, particularly those aligned with the U.S., China’s rise, as articulated through the CNYSs, may not only challenge U.S. hegemony but also pose a broader threat to Western global leadership, raising doubts about the stability of the existing international order.

For many non-Western countries, the CNYSs may indeed be viewed as a blessing. This is because China’s focus on “multilateral cooperation” aligns with the interests of these countries (Stephen, 2021). Keohane (2005) argues that international relations can reduce conflict and promote broader cooperation through the establishment of common rules and norms. For countries seeking to reduce their dependence on Western powers, China’s initiatives offer viable alternatives. China’s rise not only helps balance global hegemony but also enhances these countries’ voices in international affairs, providing them with increased economic and diplomatic opportunities.

Conclusion

This research focuses on analyzing the visionary language embedded in CNYSs—including the discursive construction of national development goals, international cooperation aspirations, and state-society relations—rather than conducting an empirical verification of reality in areas such as on-the-ground development outcomes or global geopolitical dynamics.

Within this framework, this study has significant theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, it demonstrates the effectiveness of CDA and transitivity system in analyzing China’s image through CNYSs. Additionally, this study integrates multiple disciplines, including linguistics, communication studies, and international relations, providing valuable insights into the field of national image construction. Practically, it offers a reference for other developing and emerging nations on effectively disseminating their national image through public diplomatic discourse. Furthermore, the findings are informative for media organizations and industry managers. For example, foreign media organizations can report on China’s role in global affairs more comprehensively and objectively, thereby maximizing cultural understanding. Industry managers involved in international business could develop targeted market entry strategies and create opportunities for cooperation with Chinese companies and the government.

However, a main limitation of this study is its narrow data scope, focusing solely on President Xi Jinping’s New Year speeches. This approach may not capture the full range of national messaging across different leadership periods. Meanwhile, focusing on the exclusive analysis of the English versions introduces potential subjectivity in interpretation. Accordingly, future research should expand the dataset to include New Year speeches from former Chinese leaders such as Jiang Zemin (1993–2003) and Hu Jintao (2003–2013), to facilitate historical comparisons across different political eras. Analyzing both the original Chinese versions and their English translations would also help uncover any differences in how China’s image is presented to domestic versus international audiences. Furthermore, cross-cultural comparative studies would yield valuable insights by contrasting China’s public diplomacy with that of other nations, highlighting both the commonalities and divergences in global communication practices. Addressing these areas could lead to a clearer understanding of China’s role and strategies in global communication and diplomacy.