Online lending (pinjol) has grown rapidly in Indonesia, offering quick credit access for small business owners, informal workers, and daily wage earners. Yet this expansion—often outpacing regulatory enforcement—has sparked widespread concerns about harassment, unauthorized data use, unethical debt collection, and privacy violations (Adhrianti et al., 2022; Widoyanto & Ratna, 2022). Despite repeated crackdowns on illegal platforms (Mahireksha et al., 2021) and strengthened regulatory framework for licensed services, including a 0.1% daily interest rate cap and stricter reporting requirements introduced in July 2024 by the Financial Services Authority (OJK), many Indonesians continue to rely on these services. Financial vulnerability, structural consumerism, and low financial literacy remain critical drivers, reflecting a deeper crisis in Indonesia’s digital finance ecosystem, where regulation struggles to balance innovation with public protection.

By the end of 2023, OJK reported shutting down over 6,000 illegal online lending platforms (Hannany et al., 2024). In mid-2024, the authority blocked 8,271 more platforms and by year’s end confirmed the closure of 3,240 illegal financial entities, nearly 3,000 of which were illicit lending providers (Rahmawati, 2024). These figures underscore both the vast scale of illegal operations and the enduring complexity of regulatory challenges, highlighting the urgency of examining public responses to the online lending phenomenon in Indonesia. KompasTV, MetroTV, and TVOneNews—national broadcast news outlets that also operate active YouTube channels—were major sources of online lending coverage in 2023. KompasTV has the largest subscriber base (about 16 million subscribers in 2023). However, KompasTV and MetroTV each uploaded only one video on the issue. In contrast, TVOneNews, with more than 13 million subscribers, stood out for its consistent reporting and strong audience engagement, uploading four widely viewed and commented-on videos: OJK on Legal vs. Illegal Lending (TvOneNews, 2023a), Victim Testimonies (TvOneNews, 2023b), Insider Reveals Fintech Tactics (TvOneNews, 2023c), and Loan Proxies and Non-Repayment Issues (TvOneNews, 2023d). These videos offered perspectives ranging from OJK’s regulatory framing to victim testimonies and insider accounts.

This study focuses on TVOneNews because its coverage generated the most analytically rich comment dataset on online lending in 2023. The depth and variety of user responses provide a strong foundation for examining how digital publics negotiate meaning and articulate resistance. From the perspective of symbolic convergence theory (SCT), YouTube comment sections function as rhetorical spaces where fragmented experiences coalesce into shared narratives. Agenda-setting theory further highlights how selective news coverage and YouTube’s algorithmic curation operate as gatekeeping mechanisms that amplify certain narratives while marginalizing others (Evans et al., 2022; Soares et al., 2022).

Although online lending has attracted growing attention, limited research has integrated SCT, agenda-setting theory, and algorithmic bias to examine Indonesian public discourse, particularly within digital extensions of mainstream news. To address this gap, this study is guided by the following research question:

RQ1: How do Indonesian netizens construct collective narratives and symbolic resistance toward online lending in YouTube comment sections of TVOneNews?

Literature Review

The Political Economy and Sociocultural Aspects of Online Lending in Indonesia

The rapid growth of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending in Indonesia reflects global trends in digital financialization driven by neoliberal agendas that promote technology-based financial inclusion while prioritizing market logics over social protections (Gabor & Brooks, 2016; Lapavitsas & Soydan, 2022). Neoliberalism, understood as the privileging of market rationality above social safeguards, provides a critical lens for understanding online lending. While fintech is often promoted as a solution to financial exclusion (Abad-Segura et al., 2020), it simultaneously normalizes debt and frames citizens primarily as consumers rather than protected subjects (Fontenelle & Pozzebon, 2018).

From a political economy perspective, the state often facilitates market expansion while neglecting social justice (Daud et al., 2020). During COVID-19, digital loans became a coping mechanism amid economic precarity (Najaf et al., 2021). Although the OJK has introduced licensing and governance frameworks (Atikah, 2020), regulatory loopholes persist, enforcement remains reactive—often triggered only after public pressure—and consumer protection is inadequate, underscoring the need for stronger oversight mechanisms (Janisriwati, 2021; Tritto et al., 2020).

Sociocultural dimensions reveal broader consequences, as online lending generates not only financial strain but also emotional distress, household conflict, and social discontent (Ali et al., 2023; Badrudin et al., 2025). Consumerist culture, reinforced by digital advertising and easy credit, drives younger generations into debt for non-essential spending (Muttaqin & Nuryanti, 2023; Silaswara & Kusnawan, 2022; Ye et al., 2022). These risks are compounded by low financial literacy and weak enforcement, which enable predatory practices to persist (Burchi et al., 2021; Fajar & Setianingrum, 2022; Ichwan & Kasri, 2019; Suryono et al., 2021). Moreover, algorithmic credit-scoring embeds new forms of exclusion, raising concerns about surveillance and resistance in the digital financial sector (Hearn, 2022).

Despite these challenges, digital finance offers potential benefits. P2P lending can expand access to credit for the unbanked and support micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) (Edward et al., 2023; Rahayu et al., 2023). Sustainable development, however, requires inclusive financial infrastructure, institutional accountability, and continued financial education (Suhrab et al., 2023). Some communities respond with solidarity-based practices and Islamic finance models emphasizing fairness and ethics (Albinsson & Ross, 2024; Musjtari et al., 2022).

In sum, online lending in Indonesia should be understood not merely as financial innovation but as a socio-political phenomenon that demands ethical governance and stronger consumer protection to align economic growth with public welfare.

Symbolic Convergence Theory and Public Narratives in Digital Communities

SCT offers a useful framework for analyzing how digital communities—including YouTube comment sections—construct collective meaning around complex social issues such as P2P lending. Through dramatic and emotional fantasy themes, individuals articulate concerns over debt entrapment, coercive collection practices, and systemic exploitation (Mei & Ying, 2017; G. Perreault & Ferrucci, 2019).

The process of fantasy chaining is not merely the repetition of narratives but a process of escalation, in which expressions of suffering, anger, or resistance are expanded and reinterpreted by other users. In this way, individual comments evolve into emotionally contagious discourses that strengthen shared interpretive frameworks (Bormann, 1985; Martin & Rawlins, 2018; Saffer, 2016). Over time, these recurring patterns develop into fantasy types that serve as interpretive lenses for evaluating socio-economic realities (Osei Fordjour et al., 2023).

Verbal and visual symbols function as cues that trigger convergence by activating culturally shared associations (M. F. Perreault & Perreault, 2019). In Indonesia, such symbols often carry ideological weight, from moral and religious critiques of exploitative financial practices to political denunciations of weak institutional oversight (Bahri & Hartanto, 2021; Janisriwati, 2021; Wahyuni & Turisno, 2019). These critiques resonate with broader concerns about neoliberal citizenship, in which individuals are positioned primarily as consumers rather than protected citizens, thereby reinforcing structural inequalities (Fontenelle & Pozzebon, 2018).

The accumulation of fantasy themes and symbolic cues can generate rhetorical visions—a collective worldview framing online lending not simply as a financial issue but as evidence of structural inequality, digital exploitation, and regulatory failure (Cecil et al., 2018; Marogna et al., 2022). These rhetorical visions foster solidarity, shape collective identities, and sustain digital activism (Hinnant & Hendrickson, 2012; Horila, 2017). They also intersect with critiques of algorithmic lending, which frame digital finance as both a site of exclusion and a terrain of resistance (Albinsson & Ross, 2024; Hearn, 2022).

Ultimately, SCT provides a powerful lens to understand how fragmented grievances in digital spaces transform into cohesive public narratives. It also connects symbolic communication in online communities with broader questions of regulation, governance, and consumer protection in the digital financial sector (Abad-Segura et al., 2020; Atikah, 2020).

Agenda-Setting Theory and Public Attention Toward Online Lending

Agenda-setting theory, introduced by McCombs and Shaw (1972), explains how media shape public priorities by highlighting specific issues, making them appear more important to audiences. Both traditional and digital media thus operate as agenda setters, influencing which topics enter public debate.

In digital environments, agenda-setting is reinforced by viral content, user testimonies, and platform algorithms that heighten issue salience (Guo & Vargo, 2017; Harder et al., 2017). YouTube’s recommendation system exemplifies this by amplifying dominant narratives such as ‘digital debt traps’ or ‘fintech fraud,’ while obscuring counter-narratives (Evans et al., 2022; Kaluža, 2021; Kumar, 2019).

Algorithmic bias plays a central role in this process: rather than being neutral, it reflects systemic biases embedded in data, design, and user practices (Kordzadeh & Ghasemaghaei, 2021). As a result, algorithms function as forms of gatekeeping, determining which issues are amplified and which are marginalized (Hooker, 2021; Van Dalen, 2023). These logics also foster filter bubbles and echo chambers, narrowing the public sphere by reinforcing existing preferences and limiting exposure to alternative perspectives (Areeb et al., 2023).

Recent scholarship emphasizes participatory agenda-setting, showing how publics shape media agendas through commenting, sharing, and discursive engagement (Rasul & AlSuwaidi, 2024; Schroth et al., 2020). From this perspective, agenda-setting is not exclusively controlled by mainstream media but increasingly co-produced by audiences whose contributions influence media framing.

Media coverage often concentrates on extreme or emotionally resonant cases, heightening public urgency for stronger regulation and consumer protection (Atikah, 2020; Pardosi & Primawardani, 2020). This urgency can accelerate policy responses in areas such as data protection, financial risk, and illegal lending practices (Guo & Vargo, 2017; LeGrand et al., 2023).

In sum, agenda-setting theory provides a conceptual lens to examine how media, algorithms, and publics interact in shaping social perceptions of online lending. It underscores that public communication dynamics are central to framing digital finance as a matter of social urgency, ethical governance, and regulatory reform (Badrudin et al., 2025).

Online lending in Indonesia emerges as both a financial innovation and a socio-political issue shaped by neoliberal policies, consumer culture, and regulatory gaps. SCT explains how fragmented experiences of debt and exploitation converge into collective narratives of resistance through fantasy themes and symbolic cues, while agenda-setting theory highlights how media framing, algorithmic gatekeeping, and public participation co-produce issue salience. Together, these frameworks show that discourse on online lending is simultaneously shaped by cultural meaning-making and platform dynamics, providing the foundation for a netnographic and thematic analysis of YouTube comment sections.

Methodology

We employed a descriptive qualitative approach using SCT (Bormann, 1985) and a netnographic method (Kozinets, 2022, p. 2023) to examine how online publics construct narratives and symbolic resistance toward online lending in Indonesia. User-generated content (UGC) provided insights into how meaning, distrust, and resistance are articulated in relation to financial practices (Saragih et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2023).

The dataset consisted of 4,338 YouTube comments from four TVOneNews videos on online lending. From this corpus, 1,100 comments were purposively selected for in-depth analysis, reflecting the channel’s high engagement and the diversity of perspectives expressed, ranging from regulatory statements to victim testimonies and insider accounts. From the 4,338 available comments, we included only those that were relevant to online lending, analyzable (i.e., not spam, emojis, duplicates, or off-topic), and reflective of the range of perspectives present—such as regulatory views, victim experiences, criticisms, and insider accounts. This approach ensured that the sample remained representative and suitable for in-depth qualitative analysis. Only comments written in Indonesian were included, as the study focused on capturing discourse within the main linguistic context of Indonesian online audiences; comments in English, regional languages, or other languages were excluded.

Data analysis followed four stages: (1) importing comments into NVivo, (2) coding themes through manual and automated procedures, (3) applying fantasy theme analysis (FTA) to examine symbolic cues and narrative patterns, and (4) synthesizing findings into collective narratives of vulnerability, resistance, and solidarity. Credibility was enhanced through triangulation, systematic documentation of analytic steps, and peer debriefing. Simple frequency counts of themes were added to illustrate proportional patterns without implying statistical generalization (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Data collection faced limitations common to digital research, including algorithmic filtering that may hide comments marked as spam or held for review, as well as the loss of comments that had been deleted before data extraction or restricted posts (Caplan & Boyd, 2018). As the dataset was collected on February 29, 2024, the findings represent a temporal snapshot of digital discourse. To ensure ethical rigor, all comments were anonymized in accordance with established digital research guidelines (Townsend & Wallace, 2017).

Findings

This study analyzed 4,338 YouTube comments on online lending (pinjol) in Indonesia, of which 1,100 were selected for qualitative analysis.

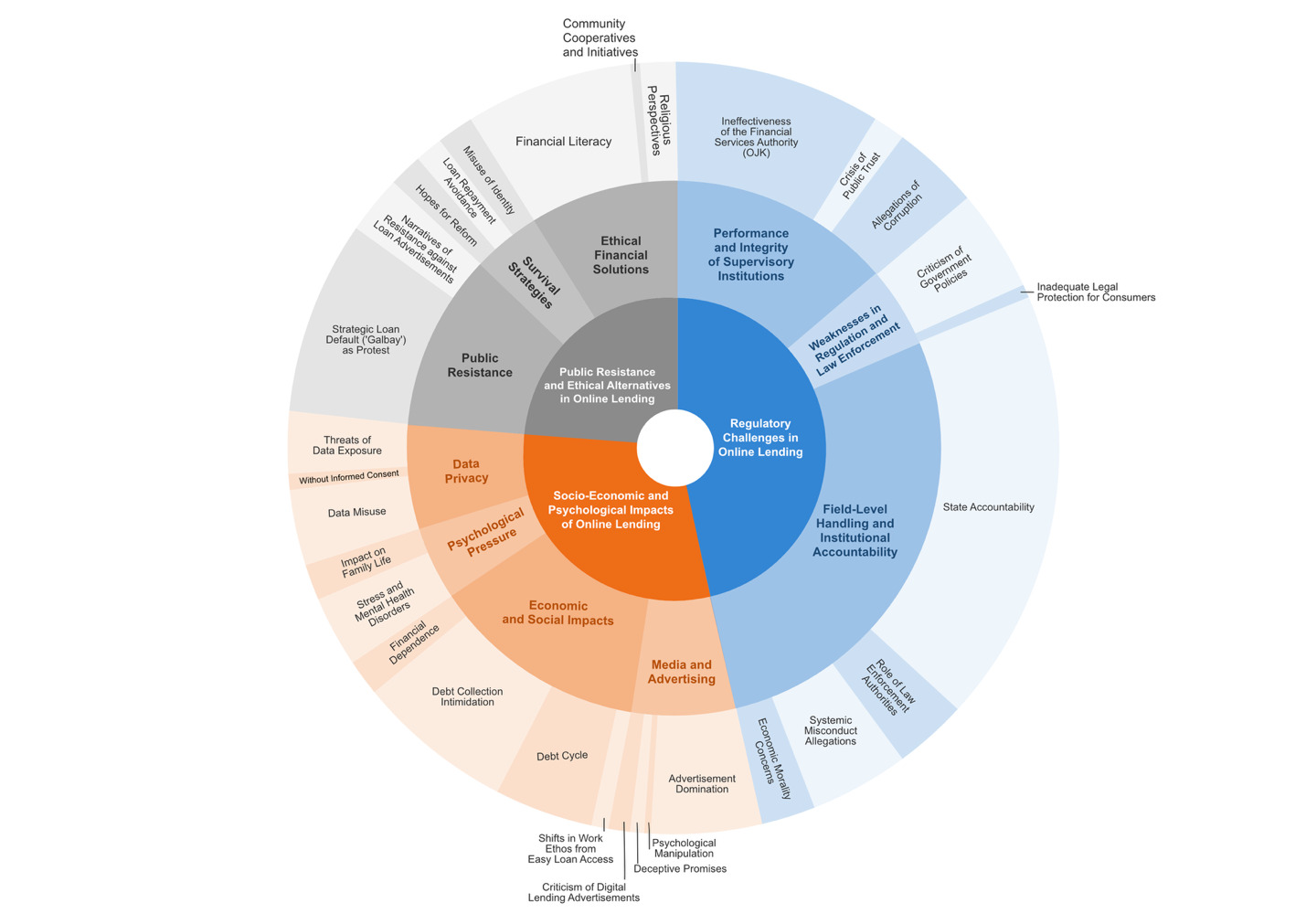

Figure 1 presents a sunburst visualization of the coding hierarchy, where the inner circle represents the three major themes and the outer sectors illustrate subthemes and sub-subthemes, with size indicating frequency.

The analysis revealed three dominant themes:

-

Regulatory challenges in online lending

-

Beyond debt: Socio-economic and psychological consequences

-

Public resistance, survival strategies, and ethical financial alternatives

These themes indicate that public discourse frames online lending not only as a regulatory and legal issue but also as a social and psychological burden, while simultaneously generating narratives of resistance and alternative practices. Each theme is elaborated below.

Regulatory Challenges in Online Lending

Table 2 presents regulatory concerns as the most prominent focus of public discourse, reflected in 514 comments. These concerns revolved around the ineffectiveness of supervisory institutions, weak regulation and enforcement, and broader questions of accountability and morality.

Public discourse revealed regulatory challenges as the dominant theme, reflecting frustration with governance failures and institutional neglect. Borrowers framed online lending not as isolated malpractice but as a systemic failure marked by absent state protection, ineffective supervision, and selective enforcement. Beyond technical shortcomings, many narratives expressed moral critiques, equating online lending with modern usury and portraying it as an assault on social justice. Taken together, these perspectives highlight a crisis of legitimacy and accountability, underscoring demands for structural reform and stronger consumer protection.

Beyond Debt: Socio-Economic and Psychological Consequences

Table 2 presents online lending not only as a financial burden but also as a source of socio-economic and psychological harm (336 comments).

Public discourse emphasized how indebtedness disrupted everyday life, extending into relationships, work ethic, and mental health. Debt collection intimidation and recurring borrowing cycles trapped borrowers in dependence and vulnerability, while emotional distress and family breakdown underscored the destabilizing psychological effects of debt. Strong criticism was also directed at manipulative digital advertising, and privacy violations revealed how personal data were weaponized for coercion. Together, these narratives portray online lending as multidimensional harm that undermines not only financial security but also personal dignity, resilience, and household stability.

Public Resistance, Survival Strategies, and Ethical Financial Solutions

Table 4 presents how borrowers and online communities responded with critiques, acts of resistance, survival strategies, and visions of ethical financial solutions (259 comments).

Borrowers reframed non-repayment (galbay) as a protest against exploitative systems, linking individual choices to collective solidarity. This oppositional discourse was complemented by pragmatic survival strategies, such as misuse of identity and repayment avoidance, which were framed as responses to structural pressures rather than acts of fraud. Many users shifted from individual coping to systemic critique, demanding stronger government intervention to regulate lenders and protect consumers. Alongside resistance and survival, participants also envisioned ethical alternatives, particularly financial literacy as a pathway to independence, the development of community cooperatives, and faith-based critiques of interest.

Taken together, these findings indicate that online lending emerges as a contested domain spanning governance, social, psychological, and moral dimensions, where netizens transform individual struggles into collective narratives of resistance and ethical imagination.

Discussion

Political-Economic Dimensions: Regulatory Failures and Corporate Influence

The findings reveal that regulatory issues dominate public discourse on online lending in Indonesia. Netizens repeatedly portray the OJK and the state as absent, ineffective, or even collusive with business actors. Hashtags such as #StopPinjol and comments like “OJK colludes with loan sharks” function as symbolic cues that stabilize fantasy themes about weak governance, forming what this study terms the absent state fantasy, in which the state is depicted as negligent and failing to protect its citizens.

These perceptions align with Tritto et al. (2020), who argue that Indonesia’s regulatory approach to P2P lending has been reactive and partial. Consequently, public discourse evolves from technical critiques of regulation into a broader crisis of legitimacy, where regulators are perceived as unable to fulfill their mandate of consumer protection.

From a political-economic perspective, these critiques resonate with broader analyses of neoliberalism and financialization. Neoliberal logics, defined as the privileging of market mechanisms over social protections, embed financial mechanisms into everyday life, including through digital debt (Gabor & Brooks, 2016; Lapavitsas & Soydan, 2022). Rather than fostering inclusion, online lending is widely perceived as an instrument of exclusion and injustice, contradicting official narratives from both government regulators and fintech companies that frame fintech as a pathway to inclusion (Abad-Segura et al., 2020).

Consistent with SCT, individual user experiences—such as “The government is doing nothing!” or “These loans are a scam by corrupt officials”—are linked through fantasy chains that connect personal grievances with systemic critiques (Saffer, 2016). This process illustrates how individual complaints escalate into emotionally resonant collective narratives. Such transformations mirror Fontenelle and Pozzebon’s (2018) analysis of how digital platforms and neoliberal discourses translate abstract financial systems into mobilizing stories of exclusion and resistance. In the context of online lending, such narratives not only expose grievances against exploitative practices but also reveal governance failures that undermine regulatory legitimacy in the digital financial sector.

These narratives crystallize around three dominant fantasy types:

-

The absent state fantasy depicts the government as silent and indifferent to citizens’ suffering, echoing Albinsson and Ross’s (2024) observation that neoliberal regimes create spaces for market dominance. As one user observed, “The government maintains silence as individuals struggle with overwhelming debt.”

-

The corporate–state collusion fantasy accuses regulators of benefiting from fintech expansion, resonating with critiques of the fusion between state and corporate interests (Guo & Vargo, 2017; Harder et al., 2017; Hearn, 2022). As expressed by one netizen, “OJK and the loan sharks are like partners—they profit while we suffer.”

-

The just state fantasy conveys normative expectations of the state as a moral authority capable of ensuring fairness, aligning with Janisriwati’s (2021) call for stronger oversight. As one user stated, “If the state is truly just, it must protect its people from digital slavery.”

Taken together, these fantasies converge into a rhetorical vision of systemic governance failure: regulatory shortcomings are not incidental but structurally embedded within Indonesia’s political–economic order (Atikah, 2020; Suryono et al., 2021). In this vision, online lending is framed not as financial innovation but as a multidimensional crisis of ethics, politics, and social justice (Daud et al., 2020; Fontenelle & Pozzebon, 2018; Gabor & Brooks, 2016; Hearn, 2022).

Socio-Economic and Psychological Consequences

This section examines the socio-economic and psychological consequences of online lending, showing how financial burdens, shifting consumption patterns, and emotional distress are collectively articulated through SCT. Within this framework, individual grievances are transformed into shared narratives that frame digital debt as both an economic burden and a psychological crisis.

The socio-economic dimension shows how collective emotions—such as fear, frustration, and distrust—shape fantasy themes that bind personal experiences into broader public narratives. These emotions serve as symbolic cues that reinforce fantasy chaining, allowing individual grievances to evolve into rhetorical visions of online lending as a social, psychological, and moral crisis (Bormann, 1985).

Online communities act as counter-publics where marginalized voices articulate discontent and construct symbolic resistance against both the state and corporations (Bahri & Hartanto, 2021). Illustrative comments such as “Our family nearly broke apart because of pinjol” and “We are trapped in endless debt” highlight how digital loans are experienced as recurring socio-psychological trauma, consistent with Ali et al. (2023) and Badrudin et al. (2025).

Beyond psychological trauma, online lending is also associated with shifting consumption patterns. The easy availability of digital credit is perceived as fostering consumerist lifestyles among younger generations (Muttaqin & Nuryanti, 2023; Silaswara & Kusnawan, 2022; Ye et al., 2022). Similar dynamics were observed globally, where the COVID-19 pandemic intensified reliance on digital loans as a survival strategy (Najaf et al., 2021). Limited financial literacy further exacerbated these vulnerabilities, as individuals lacked the capacity to manage risks or anticipate long-term consequences (Burchi et al., 2021; Ichwan & Kasri, 2019).

Within SCT, these dynamics crystallize around three fantasy types. The victimization fantasy frames borrowers as targets of intimidation, data breaches, and psychological pressure. The trapped mobility fantasy depicts digital debt as a barrier to upward mobility, entrapping borrowers in poverty rather than enabling opportunity, as illustrated in the comment, “We are forever stuck in poverty because of pinjol.” The ethical finance fantasy envisions alternatives grounded in fairness, such as cooperatives, financial literacy, or Sharia-based financing, aligning with Musjtari et al. (2022).

Low financial literacy further exacerbates vulnerability. Ichwan and Kasri (2019) and Burchi et al. (2021) emphasize that limited risk management capacity leaves individuals more prone to predatory practices. Consequently, online loans are no longer perceived as personal financial tools but as social traps that destabilize households, widen inequalities, and erode dignity.

Fantasy chaining is evident in hashtags like #GalbayMassal and slogans such as “Abolish Illegal Lending,” which bind fragmented experiences into collective visions. Public discourse critiques not only lenders but also digital platforms, with some users noting that “YouTube promotes pinjol ads, making them complicit in exploitation.” At the same time, alternative imaginaries emerged, with others suggesting that loans could be beneficial if managed ethically and transparently.

In sum, online lending in Indonesia is not perceived merely as a financial tool but as a multidimensional crisis encompassing economic vulnerability, consumerist pressures, and psychological distress. Through symbolic convergence, fragmented experiences—ranging from intimidation by debt collectors to family breakdowns—are transformed into rhetorical visions that frame digital lending as a threat to household stability, social justice, and collective well-being.

Public Resistance, Survival Strategies, and Ethical Alternatives

Digital publics are not passive victims but active agents resisting online lending. Comment data highlight three dominant modes: strategic default (galbay), survival tactics, and imaginaries of ethical finance. Viral slogans such as #GalbayMassal—often framed as protest rather than moral failure—illustrate how defaulting is reimagined as collective resistance (BBC News Indonesia, 2025; Febiola & Ariyani, 2025).

Under SCT these practices crystallize into distinct fantasy themes. The resistance fantasy portrays galbay, the rejection of loan advertisements, and hashtags like #StopPinjol as symbolic defiance. One user mocked the regulators: “OJK is crawling while Galbay is sprinting.” The survival fantasy highlights pragmatic coping strategies. As one comment noted, “I used my cousin’s ID, so the threats went to him, not me.” The ethical reform fantasy imagines alternatives rooted in literacy, solidarity, and Sharia principles. For example: “Avoid riba; it’s better to be poor than cursed.” Here, riba refers to usury or unjustified interest prohibited in Islamic finance. These narratives echo scholarship on ethical finance and calls for cooperatives or Sharia fintech as fairer systems (Musjtari et al., 2022).

These narratives intersect with political economy concerns. Regulatory loopholes and weak oversight sustain predatory lending (Atikah, 2020; Suryono et al., 2021), while digital platforms privilege corporate power over public protection (Guo & Vargo, 2017; Harder et al., 2017; Hearn, 2022). Public resistance thus challenges both state authority and neoliberal debt regimes (Daud et al., 2020; Gabor & Brooks, 2016).

Symbolically, these fantasies converge into a rhetorical vision framing online lending as a moral, political, and social crisis. Collective pronouns (“we,” “the people”) and hashtags like #StopPinjolKejam serve as cues binding individual experiences into shared imaginaries of justice and solidarity.

Theoretically, these findings extend debates on symbolic resistance (Fontenelle & Pozzebon, 2018) by showing how publics re-signify practices like galbay through fantasy chaining, moving beyond critique to articulate moral-economic reform rooted in solidarity, ethics, and participatory governance.

Media Amplification and Agenda-Setting

Media amplification and agenda-setting play a central role in shaping discourse on online lending in Indonesia, alongside regulatory failures, socio-economic consequences, and public resistance. Agenda-setting theory (McCombs & Shaw, 1972) underscores how media construct public priorities, a process further intensified in digital ecosystems by algorithms and participatory publics.

Findings show that narratives such as “digital debt traps” and “illegal fintech” gained prominence because they were amplified both by mainstream coverage and platform virality. Reporting on OJK’s list of 96 licensed lenders (Arnani, 2025; Arsika, 2025) and Task Force actions blocking more than 1,100 illegal platforms (Department of Communication and Information of East Java Province, 2025; Komdigi, 2024; Pratama, 2025) reinforced perceptions of weak regulation. Media also framed galbay not only as financial risk but also as resistance (Arini, 2025; BBC News Indonesia, 2025; Febiola & Ariyani, 2025; Ibrahim, 2025).

However, these amplification mechanisms are not neutral. YouTube’s recommendation system acts as an algorithmic gatekeeper, amplifying some narratives while muting others (Evans et al., 2022; Hooker, 2021). Algorithmic bias rooted in design and data curation fosters echo chambers (Areeb et al., 2023; Kordzadeh & Ghasemaghaei, 2021; Van Dalen, 2023). With only 62% digital literacy—the lowest in ASEAN—Indonesians are especially vulnerable to algorithmic biases, which heighten susceptibility to crisis narratives and distrust (Anam, 2023).

Agenda-setting also assumes a participatory character. Hashtags, petitions, and viral comments can propel issues from digital spaces into mainstream coverage. National media subsequently amplified the galbay narrative—initially circulated online—thereby pressuring regulators to respond more quickly (Rasul & AlSuwaidi, 2024; Schroth et al., 2020). This case illustrates that agenda-setting no longer functions in a linear, media-to-public fashion but operates interactively and multidimensionally, shaped by the interplay of media, algorithms, and public intervention.

Within SCT, hashtags such as #StopPinjol and #GalbayMassal serve as symbolic cues linking personal experiences to collective visions of crisis and justice. Media amplification and algorithmic bias accelerate fantasy chaining, transforming fragmented stories into rhetorical visions of governance failure, socio-economic trauma, and resistance.

Theoretically, these findings extend agenda-setting theory (Guo & Vargo, 2017; McCombs & Shaw, 1972), demonstrating that in digital contexts agendas are co-constructed by media, algorithms, and publics. This aligns with Guo and Vargo (2017) and LeGrand et al. (2023), who contend that amplification accelerates regulatory responses. In Indonesia, such dynamics have pressured OJK to strengthen consumer protection, curb illegal lending, and address data governance (Atikah, 2020; Pardosi & Primawardani, 2020).

Table 5 synthesizes the research themes, fantasy types (within SCT), symbolic cues/illustrative narratives, and rhetorical visions in Indonesian public discourse on online lending.

Public discourse on online lending in Indonesia centers on governance crises, socio-economic trauma, collective resistance, and media amplification. Symbols such as #StopPinjol or #GalbayMassal, together with narratives like “our family was destroyed by pinjol,” serve as cues that link individual experiences to shared rhetorical visions. SCT explains how these stories crystallize into collective imaginaries, while agenda-setting theory highlights how media, algorithms, and publics amplify issues and accelerate responses.

From these dynamics, four central rhetorical visions emerge—governance crisis, socio-economic trauma, public resistance, and media-driven distrust—showing how symbols, emotions, and media transform fragmented experiences into collective narratives of financial injustice and a broader crisis of legitimacy.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that online lending in Indonesia constitutes a multidimensional crisis encompassing regulatory, social, psychological, and moral dimensions. By integrating SCT and agenda-setting theory, it reveals how digital publics evolve from passive victims into discursive actors who challenge institutional legitimacy. Beyond the Indonesian case, the findings contribute to broader theoretical understandings of symbolic convergence in digital financial contexts and highlight how publics, algorithms, and media co-construct narratives that shape governance responses. Ultimately, this underscores the urgent global need for ethical, participatory, and inclusive approaches to fintech regulation.

This research extends SCT by showing how personal experiences in digital spaces—such as intimidation, galbay (strategic default), and family breakdown—crystallize into fantasy themes and rhetorical visions with political resonance. It also advances agenda-setting theory by demonstrating how algorithms and public participation amplify crisis and resistance narratives beyond the linear logic of traditional media. Practically, the findings highlight the urgency of stronger regulation and enforcement, improved digital and financial literacy, and the promotion of solidarity-based and Sharia-compliant financial alternatives. Taken together, the study contributes to both theoretical debates in communication and digital political economy and to the design of public policy in Indonesia’s digital financial ecosystem.

Funding

This study was funded by the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service, Ministry of Education, Culture, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, under Grant No. 0667/E5/AL.04/2024.