Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a transformative force across communication, education, governance, and social cognition. Extensive scholarship shows that AI-driven platforms shape what becomes visible, credible, and authoritative online: platforms structure information (Gillespie, 2018), algorithms determine meaning and relevance (Beer, 2017), filtering practices govern knowledge visibility (Introna, 2016), datafication reorganizes social life (Couldry & Mejias, 2019), and predictive extraction consolidates new institutional power (Zuboff, 2023). Yet this work remains fragmented across domains.

In this changing environment, public opinion research—traditionally focused on media effects and citizen attitudes—must contend with AI systems that curate information, shape cognition, and increasingly co-produce public expression. Insights from the 2025 ANPOR Roundtable[1] indicate that AI functions simultaneously as infrastructure, epistemic partner, political actor, and agenda-setting force, reshaping how societies construct public discourse, negotiate digital sovereignty, and generating legitimate knowledge.

This research note synthesizes these insights into a conceptual framework illustrating how AI restructures power in knowledge production—structurally, cognitively, globally, and communicatively. It underscores the need to rethink communication and public opinion theory in an era where human expression, algorithmic agency, and infrastructural power are deeply intertwined.

The rapid and uneven development of artificial intelligence makes theoretical integration increasingly urgent. Research notes can help chart emerging problem spaces and propose early-stage conceptual models, and the 2025 ANPOR roundtable brings together diverse regulatory, technological, and cultural perspectives well suited to this task.

While existing scholarship addresses algorithmic bias (Bender et al., 2021), platform power (Gillespie, 2018; Introna, 2016), data colonialism and digital inequality (Birhane, 2021; Couldry & Mejias, 2019), and the harms of opaque AI systems (O’Neil, 2016; Zuboff, 2023), these lines of inquiry remain largely disconnected. As a result, we lack a unified framework explaining how AI operates simultaneously as infrastructure, cognitive agent, agenda-setter, and driver of global epistemic inequality. Without such integration, public opinion theory risks drifting out of step with socio-technical realities in which AI shapes what people see, how they reason, and whose voices gain visibility. Synthesizing these strands is therefore essential for understanding the democratic and epistemic consequences of AI-mediated communication.

Methodology

Data Preparation

The analysis draws on insights from the 2025 ANPOR Roundtable on “AI, Sovereignty, and Public Opinion,” held in November 2025 at the ANPOR annual conference in Bangkok, Thailand. The session convened five scholars[2] from Monaco, Japan, China, Indonesia, and Switzerland, bringing together diverse disciplinary and geopolitical perspectives to examine emerging challenges at the intersection of AI, governance, and public communication. It provided a timely forum for exploring how transformations in AI infrastructure and regulation shape knowledge production and opinion formation.

The 60-minute discussion was transcribed verbatim and cleaned through accuracy checks, correction of inconsistencies, and removal of non-substantive utterances. Because of the participants’ disciplinary and geopolitical diversity, the transcript was analyzed not through traditional line-by-line coding but as a source of conceptual insight suitable for integrative synthesis.

To strengthen reliability, thematic coding employed two complementary modes: (1) human coders from the research team and (2) the AGI-based LLM Content & Discourse Analyzer modified by ANPOR Korea (2025). Triangulating these outputs enhanced thematic consistency, reduced coder bias, and improved pattern recognition. This dual human–AI approach—uncommon in conceptual research notes—provides a transparent analytic trail and reinforces the credibility and robustness of the resulting frameworks.

Analytic Orientation

Given the conceptual nature of a research note, the analysis followed a synthetic integrative approach rather than conventional qualitative techniques. The interpretive strategy drew on principles from qualitative integrative reviews, interpretive synthesis, and the DADA analytic framework, proceeding through four iterative stages: 1) discovering salient themes across diverse disciplinary perspectives; 2) assessing conceptual convergences, contradictions, and tensions; 3) designing an integrated theoretical architecture that connects structural, cognitive, and communicative dimensions of AI; and 4) acting by identifying implications and proposing future research trajectories.

The dual-mode coding process—combining human qualitative judgment with machine-assisted discourse analysis—further strengthened methodological rigor by cross-validating thematic boundaries and enhancing the coherence of the resulting conceptual models.

Stage 1: Thematic Discovery

Initial immersion in the transcript revealed three cross-cutting thematic domains:

AI as a Decentralization–Centralization Force

Discussants highlighted competing trajectories in AI development, including personal AI and localized data storage, open-source infrastructures, firewalled privacy-oriented systems, and the dominance of global tech platforms. These elements illustrate a core tension between distributed autonomy and centralized control in AI architectures.

AI’s Role in Reshaping Human Cognitive Agency

Discussants emphasized how AI transforms critical thinking, learning, and decision-making. Insights pointed to both cognitive augmentation and cognitive risks, including overreliance on AI outputs, declining evaluative scrutiny, and uneven digital literacy across regions.

AI as an Agenda-Setting Mechanism

The discussion highlighted how algorithmic curation structures public and policy priorities, creates personalized informational environments, and fragments mass-mediated discourse into individualized “micro-agendas.”

Stage 2: Conceptual Assessment and Cross-Comparison

Cross-synthesis across the discussants’ contributions revealed five interconnected conceptual domains: 1) personal AI and data localization, 2) collaborative intelligence and learning, 3) digital power structures and inequalities in the Global South, 4) governance and privacy models, and 5) AI-mediated agenda-setting.

These domains demonstrate that AI functions simultaneously as infrastructure, cognitive partner, socio-economic stratifier, and communicative actor. This interplay indicated the need for an integrative framework to explain how sovereignty, agency, inequality, and agenda power co-evolve within AI-mediated environments.

Stage 3: Integrative Model Construction

The synthesis of insights informed the development of two conceptual models: (1) the multi-dimension AI sovereignty and knowledge production framework (MASK-PF), and (2) the AI–opinion formation ecosystem. Together, these frameworks map AI’s influence across structural, cognitive, and communicative dimensions, demonstrating how AI reshapes both the conditions of knowledge production and the mechanisms through which opinion dynamics unfold.

Stage 4: Linking Frameworks to Scholarly Contributions

The analytic processes ultimately enabled the identification of the roundtable’s major conceptual contributions to public opinion research, which are synthesized later in this paper. These contributions clarify how AI is transforming the foundations of opinion formation, expression, measurement, and governance.

This research note prioritizes theory-building rather than empirical saturation. Expert elicitation and integrative synthesis are appropriate in rapidly evolving domains like AI, where stable datasets and constructs are limited. The five discussants’ disciplinary and geopolitical diversity is a methodological strength, enabling conceptual triangulation and the identification of multi-dimension theoretical patterns.

Findings

The purpose of the Findings is not to claim empirical finality but to articulate mid-range conceptual models that capture the structural and cognitive mechanisms through which AI reshapes public communication. These models are intended as generative heuristics—structured enough to guide empirical inquiry yet flexible enough to be refined through future comparative, computational, or experimental research.

Overview of Synthesized Insights

The thematic and conceptual synthesis of the roundtable discussion reveals that AI reshapes communication and public opinion across multiple, interdependent dimensions. Rather than influencing opinion formation in a linear manner, AI operates simultaneously as infrastructure, cognitive partner, socio-political filter, and agenda-setting actor. These functions cut across national contexts and disciplinary perspectives, producing a shared recognition among the discussants that contemporary opinion formation is embedded within a socio-technical ecosystem where algorithmic processes and human cognition are deeply intertwined. To capture this complexity, two integrative frameworks were developed: MASK-PF and the AI–opinion formation ecosystem. Each model illuminates distinct but complementary dimensions of AI’s growing role in shaping how knowledge, narratives, and public meaning circulate.

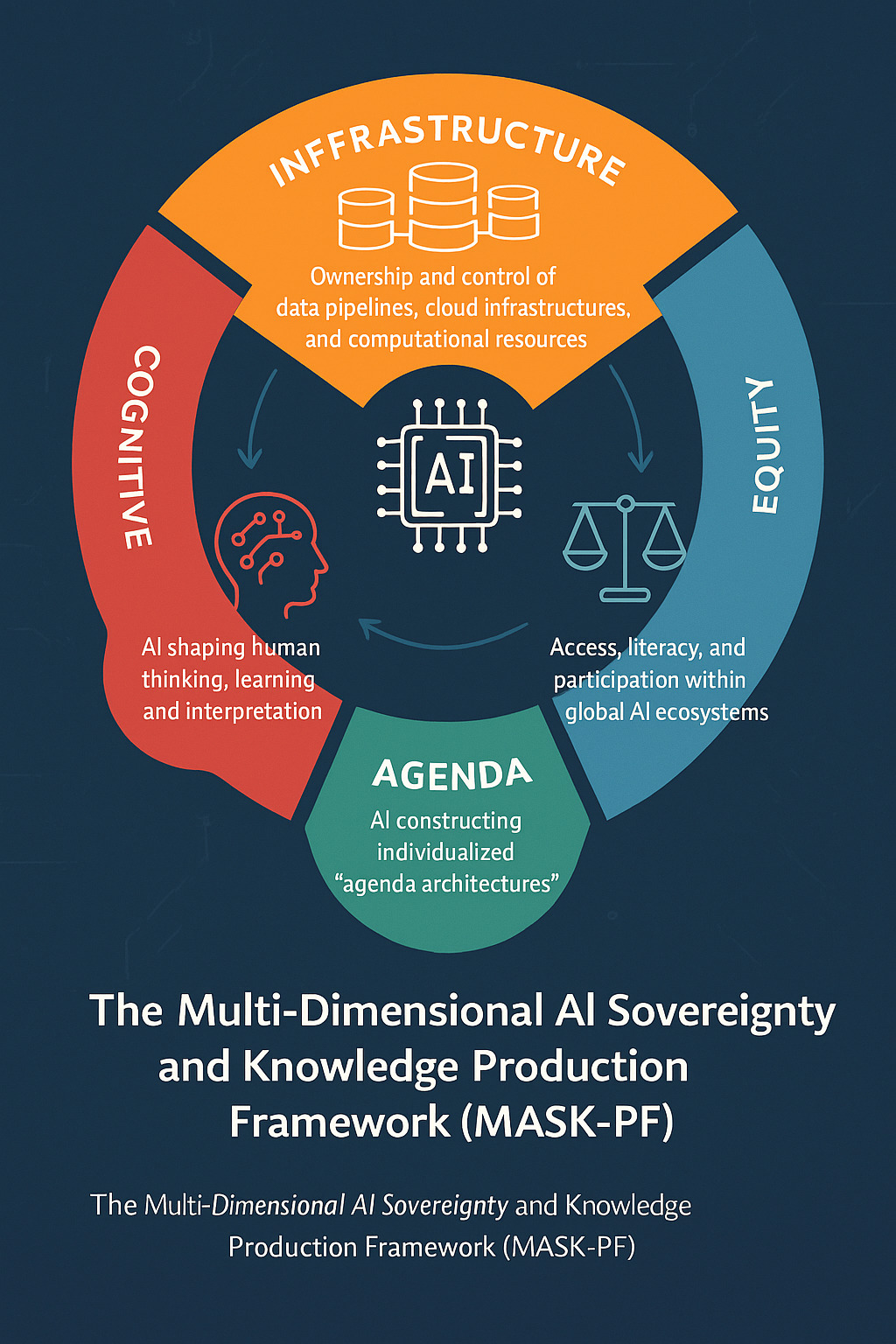

Integrative Framework 1: The Multi-Dimension AI Sovereignty and Knowledge Production Framework (MASK-PF)

The MASK-PF framework conceptualizes AI’s influence across four interdependent dimensions that together structure the conditions under which knowledge and public meaning are produced. The AI transformation includes the following dimensions.

Dimension 1 — Infrastructure: AI Infrastructure, Data Control, and Digital Sovereignty

Kartikawangi’s mapping of GAFAM dominance demonstrates how control by a handful of actors—Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft—centralizes global data flows and public discourse, reinforcing concerns about platform power (Gillespie, 2018) and surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2023). Ahvenainen’s vision of personal AIs trained on user-owned data suggests decentralized models such as data cooperatives (Pentland et al., 2021). Fujii adds a third pathway through democratically governed AI output firewalls, echoing debates on accountability and alignment (Bryson, 2018; Floridi, 2019). Together, these perspectives highlight competing sovereignties—corporate, individual, and democratic.

Dimension 2 — Cognition: Collaborative Intelligence, Cognition, and Human–AI Learning

Notari argued that learning and reasoning now unfold within collaborative intelligence ecosystems where AI agents contribute to explanation, argumentation, and conceptual refinement, aligning with extended mind theory (Clark & Chalmers, 1998) and distributed cognition research (Hollan et al., 2000). He warns that AI-generated fluency can trigger Dunning–Kruger amplification, echoing concerns about automation bias (Mosier & Skitka, 1996) and AI-induced overconfidence (Mayer, 2022). Ahvenainen extends this trajectory toward AI-to-AI communication, suggesting cognition must be understood as hybrid human–AI activity (Rahwan et al., 2019). Together, these insights show that AI reshapes foundational epistemic processes, requiring new frameworks for literacy, trust, and decision governance.

Dimension 3 — Equity: Inequality, the Global South, and Digital Voice

Kartikawangi raised the foundational question “whose voice, whose network?” by showing that Internet access, platform infrastructures, and data representation remain profoundly uneven across the Global South—a pattern aligned with research on structural digital inequality and epistemic injustice (Birhane, 2021). Luo added that Northern-centric training datasets and algorithmic curation reproduce hegemonic informational hierarchies, while limited computational resources and scarce high-quality local data constrain the corrective potential of open-source models. Together, these insights reveal intertwined inequities—data, computer, and visibility—positioning AI as a new arena of postcolonial power. Public opinion research must therefore treat global publics as structurally stratified.

Dimension 4 — Agendas: AI as Agenda Setter in Public Communication

Luo argued that AI-driven platforms now construct—rather than merely filter—public agendas, directly challenging classical agenda-setting theory (McCombs & Shaw, 1972). She further emphasized that algorithmic personalization produces individualized “agenda architectures,” deepening the fragmentation described by Pariser (2011) and Papacharissi (2015) into even more granular micro-publics. Kartikawangi added that although individuals increasingly act as agenda setters on social media, their expressions are shaped, amplified, or suppressed by platform algorithms. Ahvenainen projected an extension of this trend through AI-managed personal communication, where personal agents express user preferences. These developments expand public opinion research into algorithmic gatekeeping (Napoli, 2014), automated agenda-setting (Graefe et al., 2018), and AI-proxy communication (Guzman & Lewis, 2020), requiring agenda-setting theory to incorporate algorithmic and personal-AI agency.

MASK-PF Summary

Figure 1 reveals that the four dimensions make AI’s interdependence edge production systemic and recursive: infrastructure shapes cognition, cognition influences equity, and equity determines agenda visibility, demonstrating interdependent rather than isolated or sequential effects. The MASK-PF model thus offers a structural lens for understanding how power, knowledge, and public meaning are redistributed in AI-mediated environments.

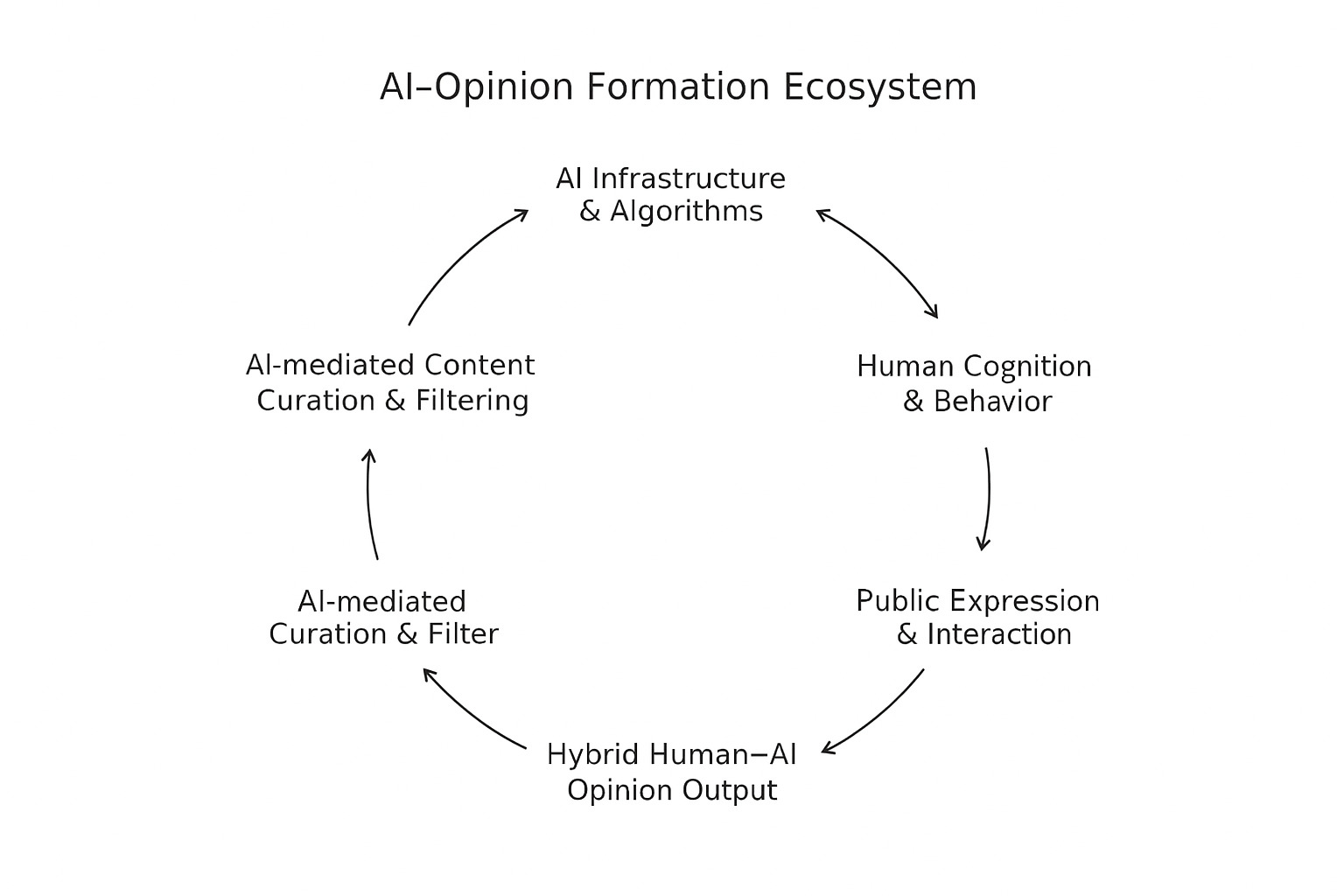

Integrative Framework 2: The AI–Opinion Formation Ecosystem

The second framework, the AI–opinion formation ecosystem conceptualizes public opinion formation as a hybrid socio-technical process co-produced by human actors, algorithmic systems, and the infrastructures that mediate their interaction. The hybrid-AI process was embedded within five interconnected elements.

AI Infrastructure and Algorithms

The AI infrastructure dimension—encompassing data systems, search engines, and recommender algorithms—now operates as a central agenda-setting force, as Kartikawangi noted in showing how control concentrated in a few actors, such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft, shapes global information flows and reinforces platform power dynamics identified by Gillespie (2018) and Zuboff (2019). Ahvenainen added that decentralized personal AI agents enhance user sovereignty but complicate opinion formation, underscoring how infrastructure governs access, visibility, and communicative agency.

Human Cognition and Behavior

The cognition dimension captures human processes—attention, interpretation, memory, critical thinking, and decision-making—increasingly shaped by AI-mediated environments. Notari argues that reasoning now unfolds within collaborative intelligence ecosystems in which humans and AI co-produce understanding, consistent with extended mind (Clark & Chalmers, 1998), distributed cognition (Hollan et al., 2000), and hybrid intelligence models (Dellermann et al., 2019). Public opinion formation thus reflects a dynamic human–algorithm interplay, complicated by cognitive risks such as AI-induced overconfidence.

AI-Mediated Content Curation and Filtering

The AI-mediated curation dimension shows how infrastructure shapes cognition by determining users’ informational exposure through algorithmic ranking, filtering, and recommend content. Luo argued that these systems construct agendas by amplifying some issues while suppressing others, making agenda formation algorithmically co-produced. Evidence from filter-bubble concerns (Pariser, 2011) to recent work on algorithmic bias (Bender et al., 2021) and emotion-driven amplification (Brady et al., 2021) demonstrates that personalization fragments publics, establishing algorithmic curation as a non-neutral gatekeeper of opinion formation.

Public Expression and Interaction

The public expression dimension captures social media posts, comments, and interactions that constitute everyday discourse. Kartikawangi noted a shift from mass-mediated publics to individualized, platform-shaped expression, where users act as micro–agenda setters yet remain driven by algorithmic incentives such as visibility and engagement. Foundational research on networked publics (Boyd, 2010; Papacharissi, 2015) continues to offer essential analytical insights, as platform-shaped visibility and algorithmically mediated expression still characterize AI-amplified communication environments, often disadvantage Global South publics.

Hybrid Human–AI Opinion Output

The hybrid human–AI opinion output dimension shows that public expression increasingly emerges through human–AI interaction. Notari’s collaborative intelligence model, which treats AI as a cognitive partner, and Ahvenainen’s “AI twin” concept—personalized agents that simulate a user’s preferences and communication style—align with Guzman and Lewis’s (2020) notion of AI proxies capable of generating or shaping expressions. Together, these developments demonstrate that public opinion spans a continuum from human-authored to fully automated outputs, requiring a reconceptualization of the “public opinion actor.”

Ecosystem Summary

Figure 2 illustrates the AI–opinion formation ecosystem as a distributed, multi-agent process shaped by human cognition, algorithmic decision-making, infrastructural architectures, and structural inequalities. Rather than a linear sequence, the model depicts a recursive system in which AI infrastructure conditions all subsequent processes, while user interactions and outputs feedback through data generation and algorithmic optimization. This cyclical structure shows that AI increasingly co-constructs, rather than merely influences, public meaning.

Cross-Framework Synthesis

Together, the MASK-PF framework and the AI–opinion formation ecosystem offer a complementary, multi-level account of how AI reshapes public meaning. The MASK-PF model maps the structural architecture of AI-mediated communication—linking infrastructure, cognition, equity, and agendas—while the AI–opinion formation ecosystem explains how these structures translate into hybrid cognition, algorithmic visibility, and human–AI co-expression in opinion dynamics.

Taken together, the two frameworks show that public opinion emerges through recursive feedback loops spanning technical systems, cognitive processes, and social hierarchies. Infrastructure shapes exposure; algorithmic curation guides interpretation; cognitive–algorithmic loops structure sense-making; inequities determine voice; and agendas are co-produced by humans and machines. This integrated view positions AI as a system-level actor that produces, filters, and amplifies opinion rather than merely mediating it.

The synthesis underscores a central insight: understanding public opinion in the AI era requires simultaneous attention to macro-level structures and micro-level processes, recognizing that neither technological architectures nor cognitive dynamics alone can account for how opinions emerge. Public opinion is now a product of interactions between human reasoning, machine computation, and the institutional forces that govern both.

Discussion

Contributions to Public Opinion Research

The roundtable’s integrative analysis contributes four major advances to contemporary public opinion research, each signaling a shift toward a socio-technical paradigm.

Reframing “Public Opinion” as AI-Mediated Opinion Formation

AI is becoming an active agenda-setter, as algorithmic curation, AI-generated recommendations, and emerging AI-to-AI interactions reshape every stage of opinion formation; as Luo noted, platforms now construct agendas, Ahvenainen anticipated personal AIs expressing opinions on users’ behalf, and Kartikawangi highlighted access inequalities—all showing that public opinion is now co-produced by humans and algorithms, requiring theories of agenda-setting and public formation to incorporate algorithmic agency.

Expanding the Unit of Analysis: From Individuals to Human–AI Assemblages

Opinion expression is increasingly a human–AI collaborative process, as Notari noted, with views emerging through collaborative intelligence and, as Ahvenainen suggested, personal AIs communicating on users’ behalf. Researchers must therefore distinguish human, co-authored, and AI-generated outputs, and incorporate AI’s role in cognition, language production, and decision-making when modeling opinion formation.

Highlighting Global Inequality in Opinion Visibility and Voice

Public opinion is shaped by global digital power structures, determined by who has connectivity, who owns platforms, and whose data trains AI. As Kartikawangi asked, “Whose voice? Whose network?” platform elites set discourse boundaries. Luo explained how Northern-centric datasets marginalize Southern perspectives, and Fujii highlighted data governance in who can speak safely. Thus, digital sovereignty and platform power are central to global opinion formation.

Introducing New Governance Concepts for Protecting Public Opinion Integrity

AI threatens the authenticity of public opinion through algorithmic amplification, misinformation, opaque prioritization, and surveillance. Fujii called for regulating AI outputs, Ahvenainen stressed decentralized data control, and Notari highlighted the need for critical thinking. As public opinion becomes increasingly AI-mediated, the need for robust and equitable socio-technical governance becomes essential. These developments reposition public opinion as a distributed, hybrid, and power-laden process shaped by cognition, algorithmic agency, infrastructure, and global inequalities.

In sum, Table 1 summarizes the roundtable’s four major contributions to public opinion research, highlighting how AI is reshaping the ways opinion is formed, expressed, measured, and governed. The cited works underpin the table’s summary: algorithms shape information exposure (Napoli, 2014; Tufekci, 2015), personalization fragments publics (Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2017), and AI blurs authorship (Guzman & Lewis, 2020), while data colonialism research shows platform infrastructures reproduce structural inequalities (Birhane, 2021; Couldry & Mejias, 2019), positioning AI as a structural participant in meaning-making.

Implications for Future Research

The roundtable identified crucial research paths for understanding public opinion in the AI era, emphasizing interdisciplinary approaches to address socio-technical complexity, global inequities, and emerging forms of human–AI collaboration across cognitive and infrastructural dimensions.

Personal AI and Multi-Agent Public Spheres

The rise of personal AI assistants and AI-to-AI interaction introduces new dynamics in public communication. Research must examine how such agents shape visibility, authenticity, authorship, and accountability as they speak on users’ behalf, requiring public opinion scholars to reconceptualize publics as multi-agent human–AI ecosystems.

Epistemic Safeguards in AI-Assisted Cognition

Notari highlighted AI’s impact on metacognition, confidence, and epistemic judgment. Future research must examine how human–AI teams negotiate truth, how AI-generated fluency shapes perceived knowledge, and which educational strategies reduce overreliance. Addressing these vulnerabilities is essential for developing epistemic safeguards in AI-mediated environments.

Global South Empowerment in AI Development

Representational inequalities highlight the need for empirical studies on how open-source models, sovereign data infrastructures, and regional AI ecosystems can empower Global South institutions. Research must identify policies, resources, and governance frameworks that enable equitable AI development and meaningful participation in global knowledge production from those in the Global South.

AI-Enabled Agenda-Setting Dynamics

Algorithmic curation in agenda-setting requires methodological innovation. Future research should use transparency tools, multimodal trace data, personal AI activity logs, and cross-national designs to examine how human and algorithmic agents co-construct agendas and how personalization shapes public discourse across contexts.

Socio-Technical Governance of Public Opinion

Fujii’s outbound-firewall governance proposal raises essential questions for democratic oversight of AI. Research must investigate who has the authority to define governance rules, how compliance can be enforced across jurisdictions, and how risks associated with AI-generated content should be evaluated. This work will be central to designing socio-technical governance frameworks capable of preserving the integrity and authenticity of opinion formation processes.

These research directions collectively underscore that AI transforms public opinion not only as a communication technology but as a structural participant in epistemic, political, and social systems. Advancing this agenda will require innovative collaborations across communication studies, political science, information science, psychology, and computational social science.

Limitations

This research note is intentionally conceptual and should be interpreted within the boundaries of early-stage theory-building. First, the analysis draws on a single 60-minute roundtable with five experts. Although the discussants represent diverse disciplinary and geopolitical perspectives, the format does not provide empirical saturation or the breadth afforded by large-scale, multi-country studies. Second, the conversational nature of the roundtable generated rich cross-domain insights but limited the depth of exploration on specific mechanisms; future work using structured interviews or focus groups could probe these areas more deeply. Third, the dual human–AGI coding process enhanced triangulation but carries constraints: human coders introduce interpretive subjectivity, while AGI systems reflect their training data and may underrepresent cultural nuances. Fourth, the MASK-PF and AI–opinion formation ecosystem models are heuristic rather than predictive and require empirical validation through surveys, experiments, computational methods, and cross-national comparison.

Conclusion

The 2025 ANPOR–APCA Roundtable Discussion underscored a foundational shift in how public opinion must be understood in the age of artificial intelligence. Public opinion is no longer produced solely through human cognition or traditional media systems; rather, it emerges from an interdependent set of dimensions involving digital infrastructure, algorithmic curation, cognitive–computational interaction, and structural inequalities in representation and visibility. AI has evolved from a communication tool into an active structural participant—one that generates information, shapes exposure, influences reasoning, and amplifies or suppresses voices within global publics.

The combined insights of the discussants demonstrate the need for a theoretical reorientation in public opinion research. The MASK-PF framework clarifies the structural and power-laden foundations of AI-mediated knowledge production, while the AI–opinion formation ecosystem illuminates the interactional processes through which human and algorithmic actors co-construct meaning. Together, these frameworks reveal the recursive feedback loops through which infrastructure shapes cognition, cognition intersects with equity, and both ultimately determine agenda visibility and public discourse.

Moving forward, scholars must conceptualize AI as a multi-dimensioned socio-technical environment shaped by global power relations, individual and collective agency, and algorithmic decision-making. Understanding public opinion now requires attention not only to human attitudes but to the technological architectures and governance systems that condition how those attitudes form, circulate, and influence democratic life. Across disciplines—from communication and political science to information science, psychology, and education—research must address the intertwined dynamics of AI governance, digital sovereignty, hybrid cognition, and structural inequality.

In a world where humans and AI increasingly co-construct social reality, developing theories and methods capable of capturing this complexity is essential. The frameworks and insights synthesized here offer a foundation for advancing this agenda and for guiding future empirical inquiry into the contours of AI-mediated public life.