The democratic electoral representation explains the tenure of political parties in power. It plays a prominent role in election outcomes (Kendall-Taylor et al., 2020). Unlike the “winner-takes-all” voting system, which restricts competition, the closed-list systems are typically adopted in democratic nations with proportionality rules that limit voting to one candidate or group (National Democratic Institute, 2018).

Citizens have a limited impact on laws and policies, so they support candidates and political parties that are most likely to satisfy their needs (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020). This encourages parties to try to sell hope, persuading the electorates to work with specific candidates that could successfully manage and benefit social and economic situations, along with maintaining or increasing their power and matching voters’ aspirations (Cwalina & Falkowski, 2015). Some parties might choose candidates that are likely to garner the maximum support, such as celebrity politicians (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020). In doing so, political parties assume that voters would perceive celebrities as more credible with less disappointing outcomes (Enders, 2018).

Celebrity politicians have become a trend in many elections (Majic et al., 2020) and essential to modern politics (Street, 2012). They have witnessed a strong presence in the political market (Jackson, 2008). Celebrity politicians are well-known individuals coming from different backgrounds with political ambitions. They use their fame to seek office and finance parties’ political campaigns, producing different acceptance levels regarding their transition from celebrity to official political outcomes in many nations (Ahmad, 2020; Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020; Boykoff & Goodman, 2009; Marsh et al., 2010; Mukherjee, 2004; Zeglen & Ewen, 2020).

Nominated by political parties to gain political influence (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020), their election success may be influenced by whether their political party is perceived as corrupt (Chang, 2020; Street, 2012) in a multi-party context (Marsh et al., 2010) in which voters could challenge the actual status quo (Jacinto, 2020) and refute political parties’ electoral support (Chang, 2020). This research follows Banerjee and Chaudhuri (2020) understanding of celebrity politicians as a product category influencing voters’ viewpoints, contributing in their judgment based on celebrity politicians background and profession as a celebrity candidate.

The category identification framework of West and Orman (2003) and Boykoff and Goodman (2009) was selected because, except for politicians, it considers the backgrounds of all Lebanese celebrities’ backgrounds that have tried to reach office in the 2009, 2013, and 2018 parliamentary elections. Consequently, celebrities in political news, acting, sports figures, athletes, business people, musicians, public intellectuals, entertainers, show business, political legacies who are descendants of well-known political families, and crime victims emerging from event tragedy scenes on the media due to some tragedy or murder of a close relative, are all considered celebrity politicians in this study.

Lebanon, a multi-party nation in the Middle East known for its political and theological strife (Badaan et al., 2020), was chosen for this study. Lebanon is a democratic nation founded on a sectarian power-sharing system with eighteen religions forming the political context, and the political parties rely on religion to sustain power (Di Mauro, 2008). Despite its weaknesses, the country survived a civil war that endured from 1975 to 1990, conflicts, invasions, and occupations by surrounding countries, and unprecedented nationwide protests against political parties in 2019. Protests broke out in Lebanon in October 2019 due to anger over rising taxes, poor public services, and pervasive government corruption (Khatib & Wallace, 2021).

In the 2009, 2013, and 2018 Lebanese parliamentary elections, the celebrity politician strategy, which is scarcely explored in Middle Eastern literature, hardly won the support of the expected voters. However, in 2017, a new electoral law based on proportionality restrictions instead of the “winner-takes-all” favored parties and limited the decisions to one candidate or group. Being a part of an electoral list was a prerequisite for any candidate to be part of the 2018 elections. They became constrained in choosing one political party or candidate that might favor the whole party list. This research tests this strategy among Lebanese voters after the 2019 uprising against political parties, acknowledging its minor success when used in the 2018 elections (National Democratic Institute, 2018).

Two potential contributing variables for shaping voting intention are suggested based on an in-depth literature review: perceived benefits and brand affinity. This study defines emotions as the affinity feeling that sheds light on the affective influence (Rambocas & Arjoon, 2019) of the party’s nomination of celebrity politicians’. However, the rationale is defined as the voting intention formed by investigating and seeking more information (Van Steenburg & Guzmán, 2019) and the perceived possible benefits (Jaca & Torneo, 2021) involving two perspectives, one from the political party that has welcomed the celebrity to understand whether voters can increase their political interests, communication, and acceptance, and another from the celebrity itself (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020).

Although there has been some progress in explaining political assessments of celebrity politicians, the literature has paid little attention to voting intention (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020). This work should help reduce this knowledge gap. Little is known about celebrity politicians’ effect on voting intention. Van Steenburg and Guzmán (2019) suggested exploring the moderating role that party brand affinity plays on voting intention, as well as the connection between the perceived benefits of a party’s celebrity politicians and voting intentions. These effects are considered in this study. This reflects a moderating effect that has not yet been investigated in a post-rebellion-sectarian-multi-party context.

To this end, the affective intelligence theory (AIT), which has impacted political science considerably, might shed light on voters’ behavior in such contexts (Marcus et al., 2011, 2019). After the October 2019 uprising against all parties, this study suggests using AIT in political decisions to explain how voters’ emotions can direct their attention to the political realm (Marcus et al., 2011), affecting their voting intention.

These findings contribute to the political marketing literature in a sectarian-multi-party, politically volatile, and geographically vulnerable nation, using appropriate measures to mitigate potential voting intention conflict. This study enables a deeper understanding of celebrity politician assessments and their advantageous incorporation as a marketing tool. It provides insight into how to reduce unfavorable voting intention among voters in the Lebanese context by elaborating on the brand affinity variable, which was missing in prior studies, contributing to expanding brand affinity effect research.

Literature Review

Affective Intelligence Theory (AIT)

Researchers have long emphasized the relationship between emotional responses and information-seeking and decision-making processes in their theories of affective intelligence. They take on two general assertions, thinking as the basis of free will and the ability of the general public to act in self-governance. The emotion’s primary function is to act as a reflexive collector of favorable or unfavorable assessments of political entities (Marcus et al., 2019).

According to neuroscience, humans have two different emotional systems, a dispositional system that considers people’s usual feelings and a surveillance system that controls their attention. Disposition systems are complex but governed by two affective facets, enthusiasm and anger (aversion), which are triggered by opposing situations, reward and punishment. Whereas surveillance systems use a variety of neurologically distinct emotions, most notably anxiety (worry, fear) or uncertainty, to signal a requirement for conscious assessment. Unlike rational choice theory, which assumes that voters always think and behave rationally under all circumstances, AIT explains voters’ judgments by switching between several decision-making modalities, arousing thoughts in two different ways, whether as implicit/explicit or unconscious/conscious process attention (Marcus et al., 2011, 2019).

Following AIT foundations, voters are expected to cast their votes following their partisanship if they usually make “standing decisions” in politics. Nevertheless, it is expected that the surveillance system would warn some voters through feelings of anxiety or fear so they may pause and reassess their first choice where affective intelligence is active (Marcus et al., 2011), thus becoming less reliant on their partisanship.

AIT and the cognitive appraisal theories of emotion predict comparable outcomes for both fear and anger in terms of behavior and decision-making. According to cognitive appraisal theories, fearful people perceive risk or danger more acutely and take risk-averse actions toward the threatening object. However, anger increases dependence on cognitive shortcuts and preconceptions regarding information processing and decreases risk perception affecting political decisions, while fear promotes attention and learning. The distinction between enthusiasm and the negative emotions, anger, anxiety, and aversion are components of various decision-making processes and have various implications on political behavior (Vasilopoulos et al., 2019). Thus, these emotions impact voters’ choices in electing the best qualified candidate to act and deliver reform promises.

Prior research has revealed the prevalence of anxiety in the general public during and following a collective action (Ni et al., 2020). This result is evidenced and tested in different contexts and by various dimensions and scales. Moreover, Gamson (1992) revealed that high levels of anger, uncertainty, and injustice are also aroused before, during, and post-protests. Also, Rico et al. (2017) argued that a perceived high-threat stimulus is a typical application of affect-driven theories, frequently with economic crises. In addition, Genovese et al. (2016) confirmed the role of financial crises in leading citizens to large protests and anticipating fear about the economic consequences.

Although political unrest and inefficiency in the government are practically constants in Lebanon, the unprecedented crises of the new proposed taxes of 2019 were more difficult on the populace than any other conflict since the civil war. World Poll results showed that Lebanon, after the 2019 protest, has experienced one of the most severe and abrupt decreases in economic and humanitarian conditions. The World Bank has classified the nation’s dilemma as a “deliberate depression” and one of the worst financial crises in the world since the 1850s and emphasized the leadership’s incompetence, placing the most defenseless citizens at high risk. Negative emotions and experiences were extremely high at the beginning of the study’s data collection in 2021, for example 49% of respondents felt anger, 56% sadness, 74% stress, and 64% worry. Additionally, 63% of Lebanese citizens wished to leave the country, 53% could not afford food, and 85% found it difficult to make ends meet (Loschky, 2021).

This research was conducted after the Lebanese uprising against political parties. Voters refuted their partisanship and had high levels of anxiety (Ni et al., 2020), anger, uncertainty, injustice (Gamson, 1992), and fear concerning the economic crisis (Genovese et al., 2016) as evidenced by (Loschky, 2021). Consequently, voters were already in the AIT disposition and surveillance systems.

Drawing on AIT, it is asserted that anger (aversion) is the emotional mechanism that converts the perceived benefits of celebrity politicians nominated by political parties into actions that refute partisanship, produce punitive activities, assign blame, and seek cognitive processing of information, all of which have a detrimental effect on voting intention. By incorporating insights from AIT and relying on Marcus, Valentino, et al. (2019) who claim that anxiety (fear) is associated with risk aversion and compromise, the logic of voters supporting competent professional celebrities as political candidates capable of reforms is presumed. Aversion and anxiety are frequently observed simultaneously and in opposition to enthusiasm. Each of these emotional qualities has a unique implication on a person’s attention to politics. In particular, enthusiasm promotes active involvement, while anger (aversion) pushes avoidance and defensive reactions to motivated reasoning (Marcus et al., 2011). It is suggested that positive voting intention depends on voters who process uncertainty, fear, and threats of economic crisis with high-affinity emotions toward celebrity politicians who can implement effective reform plans.

Voting Intention

The literature has long associated voting and purchase intentions, referring to the individual’s anticipated future behavior (Dassonneville et al., 2015; Whelan et al., 2016). Voting intention in election decision-making predicts a person’s likely behavior (Whelan et al., 2016). Although voting intention is considered a sign of political preference (Dewenter et al., 2019), it may not always translate into voting behavior (Dassonneville et al., 2017).

The determining factors of voting intention may change over time and may be impacted by electoral laws, political campaigns, rivalry, or a particular leader’s charisma (Norris, 2004). Voters typically support political and economic reforms when choosing political parties and politicians (Pasek et al., 2009). However, in a polarized electoral environment, voters are dependent on the voting options founded on experience, professional skill, and faith in the candidate’s ability (Zanotelli et al., 2020).

Voting intention can also be influenced by the level of involvement (Pinkleton, 1997), affinity voting (Mansbridge, 1999), and negative advertising as well as positive (Yoon et al., 2005). Previous studies conducted in democratic political systems have evidenced voters’ perceptions affecting their voting intention, influenced by societal and personal beliefs, preferences, and external circumstances (Lim & Snyder, 2015). Ideological orientation and moral foundations were acknowledged as the strongest voting intention predictors in some electoral contexts (Milesi, 2017). However, religious voting (Langsæther, 2019), habitual voting or past voting behavior (Cravens, 2020), and corruption voting (Chang, 2020) were also evidenced as determinants affecting voting intention.

The literature on interventions of celebrity candidates has shown conflicting results (Brockington, 2014). Celebrity density in societies such as Finland has been emphasized as an outcome of high trust within the political system and the low presence of political parties (Loader et al., 2016). Conversely, in societies with high political distrust, celebrities were generally positioned negatively (Štechová & Hájek, 2015), while in other studies, they were welcomed as alternatives to distrustful elected politicians (Inthorn & Street, 2011), highlighting the support of nonpolitical candidates where corruption was noted (Papic, 2020). Celebrities can be identified based on their accomplishments, skills, access to celebrity privileges, and level of media exposure. Public approval and recognition of celebrities in the political sector may differ (Mendick et al., 2018) as they are still not treated as seriously as political representatives.

It is a challenge to predict the success of celebrity politician strategies in political elections, especially if nominated by political parties that no longer benefit from sectarian motivations in a geographically conflicted and corrupted country (Chang, 2020; Sika, 2020). This study defines voting intention as the intention to support celebrity figures as a disposition of voter impressions.

Voters worry about the unfulfilled promised reforms, which might affect their voting choice regardless of a candidate’s formal affiliation. However, confronting past engrained voting ideologies can be challenging (Bisgaard, 2015), especially in a threatening geographical context. Moreover, political parties acknowledge the costs associated with a crisis and mass public demonstrations seeking social and economic reforms (Genovese et al., 2016). According to recent research conducted in challenging environments, voters lacking basic social and economic services like health care and job security tend to support their traditional political party (Elhajjar, 2018). Nominating professional celebrities with decent backgrounds and achievements could be viewed as a positive intention for the political parties to plan eventual reforms. Despite the perceived lack of trust in such parties, this association might give some hope to voters for a brighter future.

Perceived Benefits of Celebrity Politicians (PBCP) and Voting Intention (VI)

Perceived product benefits are the advantages that satisfy users’ needs connected to brands and competitors (Keller et al., 2011). Perceived product benefits consist of experiential benefits linked to the post-experience of the product-related attributes, functional benefits linked to the intrinsic product-related attributes and primary motivations like safety and physical needs, and symbolic benefits linked to the extrinsic non-product-related attributes uniqueness, including social approval needs, personal expression, and externally directed self-esteem that can be transferred to the brand extensions (Pourazad et al., 2019). Human beings are usually rational in using available information and tend to consider the outcomes of their probable actions before their engagement. Thus, analyzing potential benefits with intention is necessary for an accurate intention prediction.

Consequently, understanding how voters evaluate the political candidate’s brand has generated a valuable understanding of political marketing (Guzmán et al., 2015). Unconnected cognitive fields were found to motivate voters’ perceptions, motives, intentions, and behavior, such as leadership characteristics, economic, social, partisanship, and foreign policies, the social imagery of the group that supports the candidate, the emotional feelings of hope, patriotism, or responsibility aroused by the candidate, the candidate’s image, personality traits, and characteristics, the events that occur during the campaign, the candidate’s personal life, or the perceived curiosity satisfaction, knowledge, and tentative needs of trying something new and different (Newman & Sheth, 1985). Farrag and Shamma (2014) added friends, family, media influences, and religious beliefs as drivers of voting intention.

In bad economic conditions, the partisan effect loses its influence, and voters may change their voting pattern reasonably. As a result, voters select the capable candidates and parties that can reform and implement positive changes (Strumpf & Phillippe, 1999). Customers, like voters, evaluate the expected benefit outcomes from both candidates and parties, impacting their voting intention (Armstrong et al., 2019). In the political field, when political parties nominate celebrity politicians, the perceived potential benefits involve two perspectives. One perspective is from the political party that has welcomed the celebrity, and the second comes from the celebrities in question (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020).

According to Norris (2004), voting may respond to a logical trade-off between benefits and costs. However, supporting a celebrity politician that is constrained and dependent on a political party weakens the offering of reforms and could be less appealing in retaining voters’ support (Marsh et al., 2010). Voters tend to evaluate various prospective alternatives to select the most favorable one based on their needs, attitudes, and values influenced by the options offered, the outcomes of policies, and the perceptions of political parties and candidates (Jacobson & Carson, 2019).

Research has evidenced the effects of voters’ rational expectations in shaping voting behavior, such as bad governmental performance (Dewenter et al., 2019), economic conditions, and high unemployment rates in generating unexpected adverse effects on society’s voting patterns and parties’ share (Strumpf & Phillippe, 1999). Fiorina (1976) has evidenced the impact of the perceived benefits of political candidates’ on voting intention, which is mirrored by profits limited to competitive brands (Keller et al., 2011) and personal costs. Although electoral corruption changes voters’ motivations and intentions to participate in the process, the benefits of supporting specific candidates and parties are always questioned (Jaca & Torneo, 2021).

Voting intentions have long been linked to enhancing perceived benefits when boosting electoral turnout (Aldrich, 1995). Focusing on the fact that voters’ expected support rises with efficacy, honest and non-materialistic advantages might stress voters’ tendency to support the system (Novak, 2021). Voters have the opportunity to support candidates with specific traits, such as potential celebrities viewed positively as genuinely caring for their society (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020). Thus, benefits are perceived about the quality and standing of political candidates, which varies depending on the national context (Wong et al., 2011).

Political parties that nominate celebrity candidates in elections are defined as the parent brand’s affiliation. Parties seek to maximize votes by nominating appealing celebrities (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020) who can answer voters’ aspirations. When citizens depend on parties to secure basic quality services, like jobs and health aid, parties try to hold on to people for electoral benefits (Elhajjar, 2020). However, without basic services, voters might rely on rational evaluations of prospected parties and candidates’ outcomes. They free themselves from long-term partisanship and search for players with quality reform performance (Farrell & Hardiman, 2021).

As such, in the context of rebellion against political parties, voters would rationally assess celebrity politicians restrained to political parties’ agendas. Furthermore, in line with AIT logic, it is suggested that in such a context, voters with high anger (aversion) are present in the AIT disposition system, where punitive activities and partisanship refusal guide their intentions. As a result, these emotional states show the lack of perceived benefits in supporting the party and its nominated celebrity politicians. Therefore, the following hypothesis is posited:

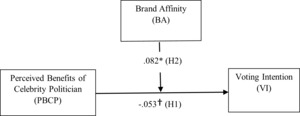

H1: Perceived benefits of party’s celebrity politician negatively predict voters’ voting intention.

The Role of Brand Affinity (BA)

According to psychological literature, all perceptions include a positive or negative effect, suggesting contradicting results (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011). Brand affinity is a positive affection developed as a degree of affective perceptions of self-resemblance that can outline the voter-candidate relationship (Dolan, 2008). Studies on the influence of emotional brand affection on management strategies have grown recently, recognizing the affinity power of encouraging strong emotional responses (Albert & Merunka, 2013). Van Gelder (2005) defined brand affinity as the attitude toward a brand that influences brand perceptions, acknowledging its capacity to affect behavior and recognizing the ability of brand attachment to measure the emotional affinities that tie user-brand interactions together personally. Affective assessments were induced by brand attachment and provocation intensity (Davies, 2008), acknowledging that emotional ties represent logical beliefs, even though attachments develop gradually through repeated interactions (Rambocas et al., 2014). According to Rambocas and Arjoon (2019), brand affinity is a behavioral prediction offered by the affect-affinity relationship that takes the complete package into account rather than simply a specific service or good. In this study, voters’ brand affinity toward celebrity politicians is a measure of likeness estimated to affect voters’ perceptions and judgments of the parties that nominated celebrity politicians in general and the celebrity politicians in question based on their professional background rather than their names.

De Chernatony and Riley (1999) state that a significant brand’s popularity and success lead to a greater brand-user emotional association. Understanding and predicting voters’ political choices and decision-making are crucial for political parties and prospective celebrity candidates. A substantial body of evidence claimed that voters make political decisions based on specific interest criteria, such as evaluating economic, personal, and financial situations in which they can reward competent performers and penalize incompetent and corrupt leaders. However, for some, personal emotional reactions toward civic matters might affect the voting decision. The mix between political cognition and personal emotions tests citizens’ proficiency in dealing with traditional democratic responsibility. Candidates are thus assessed based on voters’ emotional reactions and cognitive evaluations (Healy et al., 2009) of political parties and nominated celebrity politicians. When the brand means something to a person, its association interpretation leads to optimistic behaviors (Thellefsen & Sørensen, 2015).

Voters may support other political parties with potential goals if they no longer identify with the conventional political parties (Kendall-Taylor et al., 2020). According to research, a candidate with a favorable brand image that reflects a person’s morals can influence brand recognition and brand association if viewed as meaningful (Rambocas & Arjoon, 2019). It is expected that negative voting intention results might be changed since ethical affinity can limit deceit (Bågenholm et al., 2021).

Voters may develop brand affinities (Rambocas & Arjoon, 2019) that positively affect their brand judgments and willingness to support celebrity politicians who appeal emotionally (Banich & Compton, 2018). Specifically, in countries where political parties focus on sectarian channel divisions and services, people develop attachments and affective feelings toward specific parties (Elhajjar, 2018). However, voters’ decision-making is affected by short-term emotional feelings (Healy et al., 2009), in which they can change their political convictions back and forth based on emotions and rational evaluations influenced by momentary contexts (Elhajjar, 2018).

Since emotions are mysterious, unpredictable, and challenging to be hypothesized and measured (Marcus et al., 2019), the link between personal emotions and voting intention may need a detailed understanding.

Aversion, anxiety, and enthusiasm are three emotional qualities that each have unique implications on a person’s ability to pay attention to politics. Aversion and anxiety are frequently observed simultaneously and in opposition to enthusiasm (Marcus et al., 2011). Conversely, emotions toward candidates’ and parties’ assessments might weaken rational thinking and voting intention predictability (Vasilopoulos et al., 2019).

Accordingly, this study suggests that even when voters do not fully trust the political party they are supporting, they tend to support candidates with certain affinity feelings. In other words, if voters had an affinity towards celebrity politicians and were presented under the habitual political party, the negative benefits evaluations that affected voting outcomes might be reduced. The support of celebrity politicians in a non-favorable national multi-party context may change the voting outcomes. Thus, presenting hope and newness to the political field is emotionally attractive, although only partially believed to offer effective reforms. As a result, it would appear that brand affinity’s moderating role is sufficient for understanding the voting intention causes of the support for the celebrity politician strategy in Lebanese elections.

AIT defines two different emotional influences, first, the disposition to rely on previous behaviors or the influence of inequality growth increase, and second, anxiety in threatening situations. While the former concerns habitual behavior, the latter urges voters to search for additional information, escape from previous political identifications, and to be more open to persuasion (Vasilopoulos et al., 2019). This study explores if voters’ emotional reactions rely on habitual political behavior toward political parties as parent brands and nominated celebrity politicians’ presence in the political field. Alternatively, it may rely on the anxiety that pushes voters to seek information and rationally assess candidates’ and parties’ probable reform approaches. It suggests that emotions towards candidates can positively affect voters’ rational electoral decisions in an uprising context against all political parties.

Thus, it is suggested that voters who process uncertainty, fear, and threats of economic crisis with high-affinity emotions towards celebrity politicians who can carry out successful reform strategies positively impact voting intention. Relying on Marcus, MacKuen, and Neuman (2011), AIT suggests that emotions improve citizen rationality, contradicting the conventional wisdom that emotions obscure judgment and cause people to act irrationally rather than encourage more deliberate decision-making. Consequently, the following hypothesis is posited.

H2: Brand affinity reduces the negative relationship between the perceived benefits of a party’s celebrity politician and voters’ voting intention.

Methodology

Design, Respondents, and Process

After the October 2019 Lebanese uprising, a cross-sectional data collection method was conducted from February to July 2021 to test the hypotheses among voters from fifteen (15) electoral districts in Lebanon. According to Atallah and Zoughaib (2019), there were 3,746,327 registered voters in Lebanon. Following Lebanese electoral law, voters aged 21 and over were addressed in several community districts according to the number of voters and deputies and their religion. Specific candidates from each of the fifteen districts provided the official voters’ lists of the 2018 parliament elections, which listed and numbered each region’s voters’ names, register numbers, genders, rites, and dates of birth. To achieve an adequate stratified proportional sample and to ensure a balance across all categories, each region was split into groups according to the voters’ age, gender, and religion. Members were then randomly chosen. Diverse representatives contacted the mayors of each region to get designated voters’ contact information. Due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic during the data collection period, selected voters received a phone call encouraging them to meet with representatives on neighborhood streets rather than in private locations.

Following Malhotra et al (2017), this study determined the minimal sample size based on the samples utilized in comparable studies. It followed a study about the Lebanese youth election polling survey conducted by Statistics Lebanon Polling and Research (Statistics Lebanon, 2018) with a minimum sample size of 1,200 respondents based on the estimated proportion of registered voters in the population. As a result, 1,269 eligible responses for analysis were collected out of 1,400 contacted voters (a 90% response rate). Before collecting data, a pilot test of thirty (30) respondents, consistent with the consensus that the pilot test sample should accurately represent the target population, helped in evaluating the survey instrument’s acceptability. Minor adjustments were made based on the pretesting study. Participants responded to items about perceived benefits of celebrity politicians, brand affinity, voting intention, demographics, favorite political party, and celebrity backgrounds. The ethical research processes were confirmed, and participants were guaranteed anonymity and voluntary withdrawal rights at any time.

Measures

The measures used in this study were adapted from prior research. They used five-point Likert scales to measure voters’ perceived benefits of celebrity politicians, brand affinity, and voting intention. Twelve items were adopted from Banerjee and Chaudhuri (2020) to measure the perceived benefits of celebrity politicians. Six items were adapted from Rambocas, Kirpalani, & Simms (2014) to measure brand affinity concerning the banking context. Modifications to brand affinity measuring items were required to align with the political marketing aims of this study. Five items were adopted from Van Steenburg and Guzmán (2019) to measure voting intention, in which one item was reverse coded. Each item was subjected to expert evaluation to verify that the statements were relevant to the research objectives.

Data Analysis

This study adhered to Gaskin (2020) methods guidelines, which included the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), known as the measurement model, and the structural model for model assessment and hypothesis testing. AMOS structural equation modeling (SEM) version 24 was used for data analysis. Using AMOS with its graphical capabilities is advantageous, because it enables users to examine the links between various components and test latent variables for direct and indirect effects on many responses.

Results and Discussion

Respondents Demographics

In general, a plurality of the survey participants’ demographic information were male (56.5%), aged between 31 and 40 years old (24.4%), held a diploma degree (62.2%), worked as public sector employees (45.6%), earned between 1,500,001 and 3,000,000 Lebanese pounds (approximately $100-200 US; 30.4%), and were Shiite Muslims (29.4%). Table 1 contains demographic information about the respondents who participated in this study.

The characteristics of voters who participated in this survey are listed in Table 2. Participants were most likely to be from South 3 region (12.2%). Respondents were most likely to support forming an independent party (22.5%), while Hezbollah received the second-most support (15.4%). Participants most accepted celebrity politicians’ type was celebrity public intellectuals (44.7%), followed by celebrity business people (33.1%).

Population Proportion Representative Sample

The 1,269 respondents were analyzed in terms of point estimates of the population mean, with its margin of error to represent the population. Table 3 displays the likelihood that 95% of all feasible intervals will overlap the actual population mean.

The Exploratory Factor Analysis

The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with Maximum Likelihood extraction and oblique rotation method ensured the sampling adequacy, as evidenced by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.781, exceeding the threshold of 0.60. The inter-correlation matrix checked the EFA reliability between factors accounting for a maximum value of 0.082, far from the 0.85 thresholds and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than 0.50. The absence of cross-loadings between items evidences the EFA discriminant validity and reliability (Gaskin, 2020).

The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The measurement model tested the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) validity, reliability, goodness of fit (GoF), and common method bias (CMB). Table 4 contains the exploratory items factor loadings and the AVE values that exceeded .50 and .40 with a CR values greater than .70, confirming the CFA convergent validity. The Cronbach’s alpha values and CR confirmed the CFA construct’s reliability with values exceeding .50 and .70, respectively (Gaskin, 2020).

The CFA measurement consists of discriminant validity (CR > .70) and the AVE square roots values greater than all equivalent correlations displayed in the diagonal of Table 5, evidencing discriminant validity (Gaskin, 2020).

Outcomes for the CFA showed a significant likelihood ratio (ꭓ² = 162.870, df = 79), an acceptable minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF = 2.062 < 5), a good goodness-of-fit index (GFI = .983 > .95), a good root mean square (RMR = .034 < .05), a good comparative fit index (CFI = .989 > .95), an acceptable standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = .027 < .08), and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = .029 < .08) with a PCLOSE value of 1.00 > .05 (Gaskin, 2020). All indicate an excellent GoF between the hypothesized model and the sample data.

CMB in data is a concern, especially in the case of a cross-sectional survey data collection, in which respondents evaluate both the cause and the effect of an observed relationship. The statistical tests followed Podsakoff et al. (2003) recommendations in testing Harman’s single-factor test if accounting for a value inferior to 50%. The test indicated a value of 20.35%, evidencing the absence of common method bias in the data. In addition, the study used the common latent factor (CLF) method following Banerjee and Chaudhuri (2020) and Gaskin (2020) recommendations in examining the regression weights difference between two models, one with the latent factor and one without it for detecting values greater than .2. This study accounted for the highest regression weight difference of .02 < .2, evidencing CMB’s absence. After investigating the measurement model, the analysis advanced to the structural model analysis.

The Structural Model Evaluation

The following stage in data analysis is to generate a structural model to evaluate the relationships between constructs, but first, the model’s GoF is checked. The structural model fitness values all indicated an excellent fit. It showed a significant likelihood ratio (ꭓ² = 4024.218, df = 1279), an acceptable minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom (CMIN/DF = 3.146 < 5), a good goodness of fit index (GFI = .91 > .90), a good root mean square (RMR = .018 < .05), a good comparative fit index (CFI = .948 > .90), an acceptable standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = .056 < .08), and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = .041 < .08) with a PCLOSE value of 1.00 > .05.

This study assumes that the effect of voters’ PBCP on voting intention depends on their affinity toward the political parties’ nominated candidates. The hypotheses were tested based on the p-value in the structural model, including the interaction variable. This study followed Crowson (2020) approach to testing moderation using the double-mean-centering approach. The independent, moderator, and interaction were all double-mean-centered in SPSS and evaluated in a structural model in AMOS.

The findings of the structural model testing are detailed in Table 6, where the results support one direct hypothesis with a 90% confidence level and the indirect moderation with the conventional 95% confidence level.

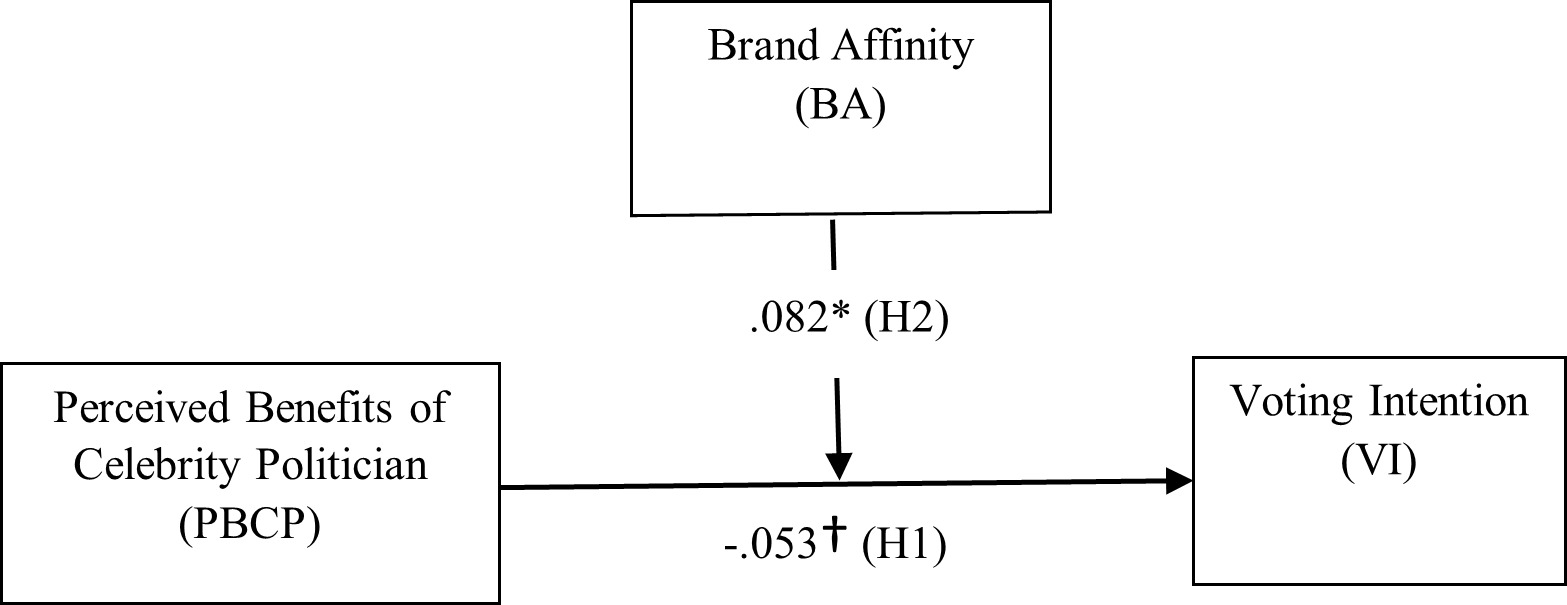

The standardized path results support the H1 with a 90% confidence level and H2 with a 95% confidence level, evidencing the positive moderating effect of brand affinity on perceived benefits and voting intention relationship to nominated celebrity politicians. These results indicate that negative slopes between perceived benefits, brand affinity, and voting intention become less negative or gradually positive the more affinity feeling a voter holds toward nominated celebrity politicians.

Figure 2 displays the plotting result of the related variables. It expresses a better interpretation of the moderating effect using the unstandardized path estimates and shows brand affinity’s reducing effect on the negative relationship between perceived benefits and voting intention. It indicates that the higher the brand affinity moderator level, the more the affected relationships are reduced.

Worth noting that the effect size of voting intention was examined and accounted for a value of .005, determined to be a small size by Aguinis et al. (2005). According to Gaskin (2020), even small effects can significantly contribute to the literature by adding meanings to the model and consequent implications. Furthermore, since one theorized path was found only significant at the 90% confidence level and in congruence with the model’s strength in detecting significant actual effects, a post hoc power analysis, according to Soper (2015), is conducted using an estimate at the 95% confidence level. A statistical power score of .99, greater than the .8 criteria, suggests sufficient power to confirm the path significance of all models in this investigation.

Discussion

This study analyzes an important trending concept in political marketing, the “celebrity politician.” It has attempted to evaluate the strategy’s acceptance in a post-rebellion Middle Eastern multi-party-confessional and corrupt country, Lebanon (Sika, 2020).

The predictor of the voting intention, the perceived benefits of celebrity politicians, had a significant negative influence on the .1 level (H1). This result is consistent with previous research (Armstrong et al., 2019; Farrell & Hardiman, 2021; Fiorina, 1976; Jaca & Torneo, 2021; Keller et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2011), which showed that perceived benefits are one of the significant variables affecting voting intention. Perceived benefits were measures involving two perspectives, one from the political party that has welcomed the celebrity to understand whether voters can increase their political attention, interests, communication, and party’s acceptance, and another from the celebrities in question (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2020). Citizens previously attached to political parties have protested against all parties because they failed for decades to provide the most minor financial, economic, social, and societal rights. Citizens have renounced their partisanship due to eras of ineffective political tactics. Moreover, they viewed any advantage in supporting a political party or its candidate as unfavorable, even if they nominate celebrities. Voters behaving under AIT restrict their attention and deliberately evaluate candidates, avoiding relying on partisanship and enthusiasm. They are angry and seeking sanctions. Shifting voters’ perceptions of such nominations from rationally non-beneficial to beneficial might assist people in avoiding party sanctions, enthusiastically believing in the party’s reform, and supporting candidates who can create a brighter future. Instead of unfulfilled promises, parties might propose actual, viable, time-bound laws and projects analyzed by renowned experts and illustrate the possibility of gaining quantifiable benefits.

It adheres to Rambocas and Arjoon (2019) brand affinity concept as a behavioral prediction in the affect-affinity relationship that considers the political party and its celebrity candidate. Voters were asked to evaluate the celebrities the party nominated based on their emotional connection to them and their likeability, uniqueness, personality suitability, pride, and happiness. As a result, voters’ brand affinity substantially negatively affected voting intention. This result is consistent with prior studies (Albert & Merunka, 2013; Davies, 2008; Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011; Rambocas et al., 2014) that established the influence of affective appraisals on logical beliefs and behavior. This finding contradicts Thellefsen and Sørensen (2015), who demonstrated that positive affection develops in proportion to the degree of affective perception of self-resemblance, although the majority of respondents were educated and supported the celebrity public intellectuals.

The results of this study demonstrate the moderating effect of brand affinity on the negative effect of perceived benefits of celebrity politicians on voting intention. The interaction between perceived benefits and brand affinity showed a significant positive moderating effect (H2). The rationale behind this finding is that a likable and unique celebrities can suit voters’ personalities after considering and assessing decision-making. According to AIT, voters are in the dispositional system where fear, anger, and uncertainty make them follow their standing decisions (Marcus et al., 2011) or even shift to another party that matches their engrained sectarian ideologies. The research demonstrates that feelings toward candidates and parties influence voting intention through the interplay of cognitive and emotional judgments based on momentary circumstances and that this interaction is primarily driven by a desire to avoid the risk of emotional biases engendering voters’ perceptions and undermining the competency and willingness of the party and candidates to engage in reform. The finding evidences that emotions toward candidates and parties influence voting intention in interrelating between rational and emotional evaluations depending on momentary circumstances, guided mainly by risk aversion (Healy et al., 2009). However, this result might be directed by voters’ constraints in choosing one party and probably one candidate during Lebanese elections.

This study’s results provide insight to further study on the role of brand affinity in multiple political contexts. It enlightens political parties in selecting better candidates and managing candidates’ nominations to achieve better electoral outcomes. However, the moderating effect is minimal, if not negligible. Knowing that the data was collected during an uprising against all parties, this result might be questioned whether voters would not re-affiliate with parties and support their nominated candidates in a calmer environment whether they had an affinity feeling toward them or not. As such, this study gives insights into voters’ views regarding parties and candidates in a worrying context instead of a calm one. While perceiving negative benefits from supporting a party’s nomination of celebrity politicians, voters with high-affinity feelings toward celebrities may reduce the negative perception and turn it into positive support. These expected insights shed light on celebrities with political motivation, refuted parties who aim for vote maximization in elections, and pushed political parties into nominating celebrities with high voters’ affinity feelings.

Understanding the conditional influence of voters’ dispositions and intentions on supporting risky political choices can help political parties and experts select appealing celebrities (Vasilopoulos et al., 2019). AIT in this study contributes to the understanding of voters’ perceptions of celebrity candidates in terms of benefits from celebrities and parties tested in a disrupted context in conjunction with their affective feeling and evaluation. It describes voters’ rational and emotional evaluations, arguing that voters may change evaluations back and forth based on the actual context.

There is a lack of research on celebrity politicians, especially in the Arab world. Uncovering empirically emotional and personal psychological factors such as anger, anxiety, fear, uncertainty, enthusiasm, or hopelessness can better contribute to the AIT literature and the acceptance of celebrities when nominated by parties in a turbulent multi-party system. Furthermore, the experience with celebrity politicians as incumbents that can influence voting intention and behavior can offer a better understanding of voters’ perceptions of nominated candidates, mainly if evaluated in a stable environment. Thus, testing the actual, past, and habitual voting behavior is a significant issue for future research.

Lebanon is a democratic multi-party system with high sectarian division and political constraints that differ from the Arab countries. Conducting this study in different contexts may lead to disparate findings. Thus, it is not easy to generalize this study’s findings. Replication studies might extend the celebrity politicians’ understanding of multiple cultures. This study was limited to one country and used cross-sectional self-reporting questionnaires. As such, it does not support causality. Therefore, a longitudinal investigation with mixed methods can foster generalizability and causality.